ABSTRACT Since the Industrial Revolution, human well-being has been dramatically improved. There are, needless to say, significant and serious gaps in this improvement, if we look globally. But, on balance and using a large number of measures, we must conclude that international development over the last 200-plus years has been phenomenal. This progress has resulted from the individual and collective efforts of humans- as embodied in the private sector. However, institutions, and especially those that are manifested as the state, facilitate the efforts of the private sector. It is an axiom that public institutions are necessary for civilization. In a society that has successfully developed, these public institutions must be pro-development, and can hence be referred to as a developmental state. Importantly, these developmental states expand their activities over time, and inevitably become international developmental states. Paradoxically, those very same public institutions that enable progress have, always and everywhere, the propensity to behave in ways contrary to facilitating progress, becoming anti-developmental. This paper outlines first the successes of the developmental states, and then the inescapable proclivity for developmental states to become anti-developmental, highlighting the inevitable consequential dilemma of how to pursue and achieve the following twin goals: filling in the gaps of global development, and, correcting the tendency for developmental states to become anti-developmental.

Keywords: The State, International development, Capacity/freedom, Developmental state

INTRODUCTION

If there is one thing we learnt from the 20th century (and there should be many, many more), it is that the role of the state is a conten- tious issue. The conflicts between Totalitarianism/Communism and Liberalism in World War Two and the Cold War were fundamentally between ideologies that had irreconcilable beliefs concerning the role of the state. Indeed, in the post-Cold War period, despite the purported victory of Liberalism, we could say it is differing opinions regarding this that is the primary factor that divides people politically. In this way, it is the role of the state that is at the core of many, or most, issues of public debate. Simply put, the political Left advocate for a larger role for the state, while the political Right call for a limited role. It is of course, more of a spectrum, with large variance between the two extremes. Importantly, if we are to examine the role of the state in society, then we are really evaluating the relationship between the state and society, and this means we are inquiring into the relationship between the state, as the collective’s institution of ultimate authority, and individual citizens. A primary purpose of this paper is to reject the ideological approach to the role of the state in society and the economy, and to instead argue that the role of the state is dependent instead on local conditions, specifically the level of socio-economic development.

The European migrant crisis is a clear manifestation of the delicate issue of the role of the state in society. It is indisputable that the European states have successfully developed their societies to the point whereby their way of life is attractive enough to motivate millions of refugees/economic migrants to undertake the extremely dangerous journey from their home to Europe. Likewise, it is indisputable that many of the states in these migrant’s home countries have failed to develop in a way that would encourage their citizens to stay. As is shown by countless surveys though, the citizens of Europe feel their states have failed to properly protect their borders. Evidently, there are state failures on both sides. Clearly too, there are enormous gaps in the levels of human well-being, even in regions so proximate as Europe, the Middle-East and Africa. Whilst gaps are an inevitable outcome of development, the migrant crisis has shown that the bottom end of the development ladder is so low that it poses a direct and substantial threat to the well-being of those at the top of the development ladder. Undeniably, international development matters to all.

It is demonstrably true that we, as a species, have made enormous progress in improving human well-being over the past 200-plus years. Whilst, there have inevitably been costs to this progress, on balance we must conclude that the benefits far, far outweigh the costs. How have we achieved such success? It is capitalism and the private sector, people and communities of people, that are the prime drivers of progress. Innovation and technology have enabled leaps in productivity that underpin the improvements in human well-being. However, and this is key, institutions provide the framework for this progress. Social institutions are necessary for cooperation. In this way, the state, and the ultimate authority it is endowed with, is a fundamentally necessary institution that provides security and stability through the provision of law and order. It is a premise of this paper that individual freedom/ liberty is both a necessary component, and the ultimate goal, of development. However, and herein lies the paradox, liberty needs capacity, and at lower levels of development, capacity is lacking. It is here that we find the solution in the Developmental State. But, and herein lies yet another paradox, institutions, and especially institutions that have ultimate authority and supreme power, will always and everywhere tend towards oligarchy. This means that the state always has a strong propensity towards serving its self-interest, and a concurrent propensity towards continual expansion, resulting in Anti-development. If we return to our lessons from the 20th century, then it is incontrovertible that the continual expansion of state power will always and everywhere result in the mass murder of its citizens (Soviet Union and Communist China being two clear examples).

This paper will begin by outlining the progress we have made as a species in the last two hundred years. It will then provide an explanation of the theoretical framework for the analysis of the role of the state in development: the tripartite relationship between capacity, freedom and institutions. Following is an analysis of the success of the development state, and the inevitable internationalization of its activities. Then, an explanation of the inevitability of the anti-developmental tendencies of the state is given. Finally, this paper offers a possible solution to the propensity for the state to become anti-developmental.

PROGRESS SO FAR

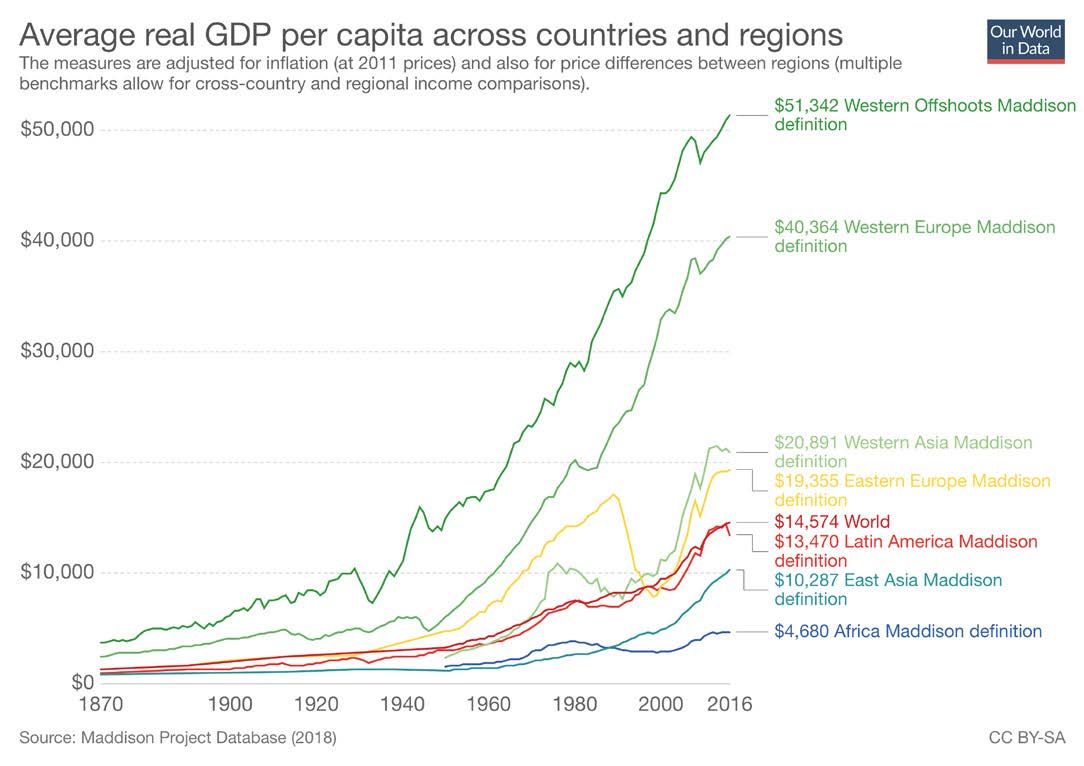

In 2016, then-President of the United States, Barak Obama said, “If you had to choose one moment in history in which you could be born, and you didn’t know ahead of time who you were going to be… You’d choose right now” (The White House, Office of the Press Secretary 2016). This author will extrapolate that bold statement to say that, generally speaking, now is the best time to be alive. For most of the 100,000 years of human history, life expectancy was perhaps 25-30 years. World life expectancy is now almost triple that. Over most of the last 100,000 years, parents have buried more than half their sons and daughters before their first birthday. Now, the global average for infant mortality is less than 30 per 1,000 live births. For most of human history, up to 60 percent of deaths occurred in warfare (Pinker, 2011). Today, less than one percent of deaths are because of warfare. Even just 200 years ago, over 90 percent of the one billion humans lived in conditions of poverty, even extreme poverty. Today, of the more than 7 billion humans, less than 10 percent live in poverty. In 1820, world average per capita GDP was just 1,263 (PPP, 2011 International Dollars). Two hundred years later in 2016, it was 14,574 (PPP, 2011 International Dollars). This was a more than 10-fold increase (using the Maddison definition). In the 1960s, in developing countries, food consumption was just over 2,000 k-cals per capita per day. Fifty years later, the figure was almost 3,000. According to the Flynn Effect, average IQ scores rise as countries develop, and this has been recorded through the 20th century. In the UK, for example, children’s average IQ scores rose by 14 points between 1942 and 2008 (Flynn, 2009). The number of democracies has increased from just a handful two hundred years ago, to almost 100 in the 2010s (Polity Score of the Polity Project). This means that about four billion people live in political systems where citizens participate in politics, where freedom is protected by law, and where the exercise of power by the state is constrained constitutionally. Using these measures of human wellbeing, it is indisputable that the human condition has improved dramatically, within the last 200-plus years, and especially since the end of WWII. Importantly however, there is a disturbing and pervasive unawareness of this. As pointed out by Hans Rosling (2018), on average just 7% of people in advanced countries are aware that the number of people in extreme poverty has been halved in the last twenty years (p. 6).

So, human civilization has leapt forward in the last 200-plus years, highlighting that development is not homogeneous across time. Progress has also not been, nor indeed can be, homogeneous across space. Some regions have led, others followed. Some regions have followed quickly, others have followed later, but in leaps and bounds. Others too, have followed slowly, substantial progress seemingly elusive. Even though average life expectancy had risen to 72 years by 2015, 21 countries had life expectancies of less than 60 years. There are five countries that have infant mortality rates of nearly 100, meaning that about 1 in 10 infants die before the age of one. Even though the level of inter-state warfare has dropped dramatically, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that worldwide, there are 25 million refugees. There are 14 countries in which over half of the people live in extreme poverty, on an income of less that US$1.90 a day. There are about 50 countries in the world where more than one-third of the population live below the national poverty line. According to the World Food Programme (WFP), almost 800 million people do not have enough food to lead a healthy life, and one-quarter of the people in sub-Saharan Africa are undernourished. There are about 30 countries that have a per capita GDP of less than US$1,000, there are 50 countries with less than US$2,000, and there are just under 100 countries that have a per capita GDP of less than US$5,000. Clearly, despite the global progress of the last 200-plus years, there are pockets where the human condition has not improved so dramatically.

DEVELOPMENT: FREEDOM/CAPACITY

How do we define development and progress? Should we per- haps begin with “Civilization is progress and progress is civilization”? (Hayek, 1960). We could rephrase this to say that development and progress is the promotion of human flourishing, and that civilization is the manifestation of this. After the last ice-age, a period of warming allowed for the Neolithic Revolution that entailed a shift in human activity from hunter-gathering to agriculture. This occurred just over 10,000 years ago and began in what is today called the Middle-East. Institutions were a key component of this shift to agriculture and indeed have played a key role in progress and development since. If we use a shorter time frame than 10,000 years, then perhaps the 3,000-year history of Western civilization is pertinent, in that it was the foundation for the Enlightenment, the Scientific Revolution and the Industrial Revolution.

Such progress is enabled by the capacity for cooperation that exists between individuals. Importantly, as pointed out by John Stuart Mill, this capacity for cooperation entails a ‘sacrifice of some portion of the individual will, for a common purpose’ (Mill, 1997). However, it is the expanded benefits received from the products of cooperation that allows the sacrifice to be borne. While cooperation necessitates an individual sacrifice for a common good or reciprocated good, importantly though, it must be undertaken without coercion. Hayek (1960) defines coercion as the manipulation of the environment in which another operates in order to get an unreciprocated benefit (p. 200). In this way, individual freedom is necessary for maximizing the productivity of cooperation.

Amartya Sen (2000) identified two primary reasons why freedom is central to development. Firstly, the purpose of development is to enhance freedom, and secondly because freedom, or the ‘free agency of people’, is necessary for development (p. 4). Therefore, freedom is the ability to achieve goals that one values. Importantly, freedom to achieve means the capacity to achieve something, and therefore freedom is an instrument through which humans actualize their goals. Sen termed this approach the ‘agency aspect’ of the individual, meaning that the individual is the agent “who acts and brings about change” (pp. 18-19). In this way, it is a capabilities approach to economic development, and it necessitates the independence of the individual, or to rephrase, the Sovereignty of the Individual. Sen connects his definitions of freedom and capacity to those of Aristotle’s use of ‘flourishing’ and ‘capacity’ (p. 24). Importantly, Sen recognizes the institutional arrangements that facilitate the enhancement of these freedoms. John Stuart Mill also stated that, “Municipal institutions are to liberty what primary schools are to knowledge… Without municipal institutions, a nation may give itself a free government, but it has not the spirit of freedom” (Mill, 1997). It seems somewhat paradoxical that institutions, that constrain and regulate, are necessary for freedom and development. However, it is an axiom of human society.

We therefore must conclude that the real drivers of progress are individual people who voluntarily cooperate to achieve common goals. However, institutions are enablers of cooperation. So, development and progress, in other words ‘civilization’, results from the interdependence and interaction between freedom, capacity and institutions, as shown in Figures 1 and 2. Each of these has co-existed, indeed co-evolved, to bring us the benefits previously outlined.

Figure 1. Institutions and the capabilities approach.

Figure 2. Capabilities approach.

THE STATE AS FACILITATOR

The concentration of power in one hierarchical organization created social conditions of security that facilitated cooperation which enabled increases in productivity. While state-like institutions have existed for millennia, we must look at the modern nation-state, because it is only under this state that broad and inclusive economic development has occurred.

Acemoglu and Robinson (2013) postulate that there are two kinds of public institutions. There are ‘extractive’ institutions which are ‘captured’ by a small group that use the institution to exploit the rest. Conversely, there are ‘inclusive’ institutions through which broad- based, national development is possible (p. 73-6). These inclusive institutions are basically democratic, and are found largely, though not exclusively, within the Liberal democracies of the West.

Adam Smith (2007) identified three duties of ‘a sovereign or commonwealth’. The first was to secure the territory through the provision of national defense (p. 536-7). The second was to provide for internal order and security though a legal system, which upholds justice for all and protects property rights (p. 549-50). In essence, these first two functions are merely the creation of order. The final necessary role of the government was to fund ‘public institutions and public works’ (p. 559-60), meaning certain public goods “that the profit could never repay the expense to any individual, or small number of individuals…” According to Smith (2004), these institutions ‘are chiefly for facilitating the commerce of the society’. Here Smith specifically refers to the infrastructure that enables the free movement of goods and people, and to the institutions that facilitate commerce. It is this third necessary function that encapsulates the developmental state. Smith is referring to public goods that cannot be provided by the market, as well as to the rules and regulations, enforced by the state, that enable development. Importantly though, and this is a key point for this paper, Adam Smith stated that, “the performance of this duty [the maintenance of public institutions and public works] requires, too, very different degrees of expense in the different periods of society” (p. 559). In essence, this is stating that the level of state intervention depends on the level of economic development.

For John Locke (1764), progress was only possible if individual liberty was protected by the state, “where there is no law, there is no freedom” (Chapter VI). He argued that not only was the state a necessary condition for cooperation and hence progress, but also that the power of the state over its citizens should be kept to a bare minimum. In this way, state interventions for the purpose of development are essentially a balancing act. The state is balancing capacity and freedom, attempting to facilitate capacity development, whilst not overly restricting freedom, because of the negative impact on capacity, and hence productivity.

DEVELOPMENTAL STATES

The term developmental state usually refers to those (successful) states that intervene to large extents in the market economy of their nation. Countries such as Japan, South Korea and China have often been referred to as developmental states. In this paper however, we will refer to all states that intervene in their national economies beyond the first two functions of a state (as put forward by Smith) as developmental states. Obviously then, this refers to states that have traditionally interfered very little in their national market economies, such as the US, to the far other extreme where the national economy and the state are to all intents and purposes synonymous, such as the former Soviet Union. Consequently, we could say that any state which is pro-development is a developmental state.

England was the first to industrialize and so had an advantage, but it was still sometimes deemed necessary for the state to intervene considerably in the economy to protect the interests of certain domestic stakeholders. For example, the Navigation Acts, first passed in 1651, prohibited foreign ships from transporting goods into England or its colonies. Over the next 200 years, these Acts allowed England to monopolize international trade. Even in the 19th century, the federal government in the US played some (limited) role in supporting economic development. In the 1860s, the transcontinental railroad in the US was supported by the federal government through the issuance of government bonds and through grants of land to the companies that built the railroads. In the 20th century, many of the early industrializers began to become what would later be called Welfare States, following Keynesian economics, pursuing full employment and broad welfare programs. During the Great Depression, the government of Franklin Roosevelt initiated the New Deals, which saw an expansion in federal spending and state interventions in the economy. A large number of new federal agencies were created, and Social Security was established in the US for the first time.

However, “late-developing countries… have relied heavily on state support in the industrialization process” (Chibber, 2014). Whilst we should not ignore the international systemic factors that contributed to the success of countries such as Japan and South Korea, we must conclude that state interventions were instrumental. In essence, “the state steps in to provide resources that they [the private sector] lack and to protect them” (Chibber, 2014). Chalmers Johnson (1982), focusing on the operation of the then-Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), argued persuasively that Japan was a Plan Rational State (p. 16-17), which is a particular type of Developmental State. MITI itself called this the ‘plan-oriented market economy system’ (Industrial Structure Council, 1975). The successful case of Japan’s development highlights the close partnership between the public and private sectors that underpins the successful developmental state. For example, the Ministry of Finance was able, through the Bank of Japan, to direct financing to favored industries, and this was a method through which the state guided the economy with ‘industrial policy’. The World Bank (1997) termed such interventions, ‘mechanisms for market enhancement’ (p. 7), and admitted the success of the developmental state. In the case of South Korea too, the state, under the leadership of General Park Chung Hee, directly guided economic development though the Economic Planning Board which ‘allocated resources, directed the flow of credit, and formulated all of South Korea’s economic plans’ (Savada & Shaw, 1997).

Figure 3. Average GDP growth.

As can be seen from Figure 3, the varying models of the developmental state have been successful to varying degrees, with the clear exception of the Communist Plan Ideological approach which has all but disappeared. It is clear that, on balance, state interventions in the economy can be highly beneficial for the citizens. However, as always, there are costs, and it is this paper’s contention that as national economies develop, there is a high potential for these costs to begin to outweigh the benefits.

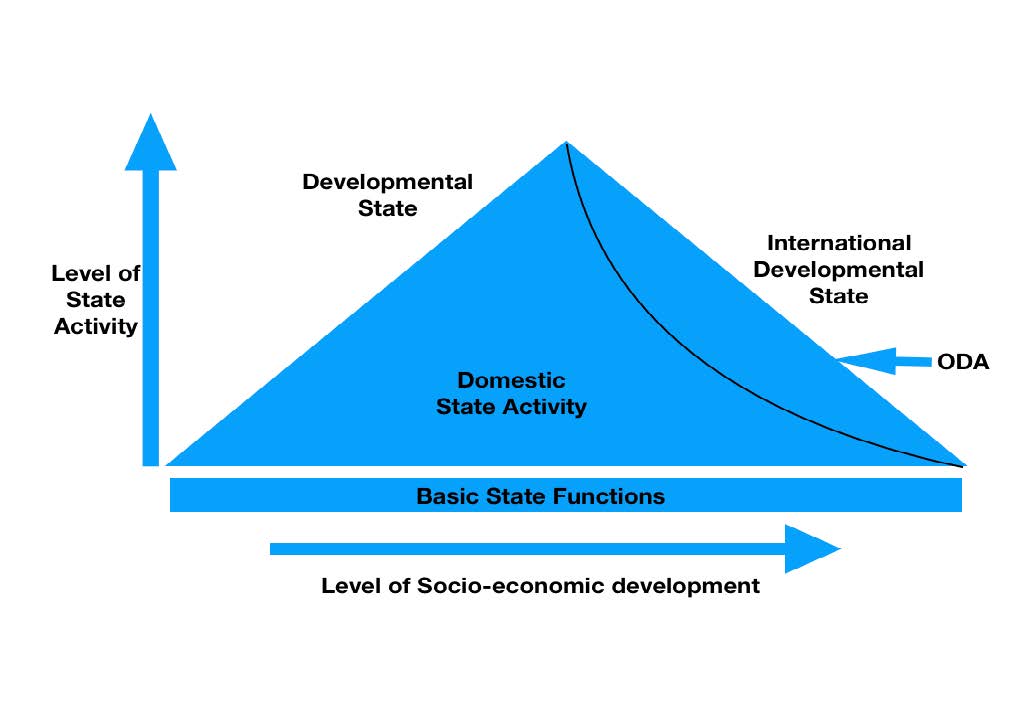

One final important point is that all development states become international developmental states. This is because as the economy expands, the interests of domestic private and public stakeholders become international. This necessitates an internationalization of state activities, which comes in many forms; participation in international organizations, negotiation of international agreements, support for the overseas operations of national public and private corporations, the provision of development assistance, etc. All such functions are natural components in the evolution of a successful developmental state.

OFFICIAL DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE

The provision of development aid from one country to another has for long been a controversial issue. Criticisms such as the following are plentiful: “the tragedy in which the West spent $2.3 trillion on foreign aid over the last five decades and still had not managed to get twelve-cent medicines to children to prevent half of all malaria deaths” (Easterly, 2007). Dambisa Moyo (2009) went further, arguing that ODA was in fact contributing to underdevelopment in Africa because it incentivizes corruption, and because it encourages dependency. This is of course a similar point to that previously made regarding the propensity for the developmental state to become anti-developmental. Some have claimed that ODA is a tool through which the rich countries of the OECD maintain dominance over poor countries. As far back as 1971, Teresa Hayter (1971), claimed that aid provided by the World Bank and OECD countries ‘serves first and foremost the interests of Western nations and their multinational corporations’. This is supported by an account of the relationship between the IMF and the government of Ethiopia in the late-1990s, as conveyed by Joseph Stiglitz (2002), who states that, while the perceived ‘intrusive- ness smacked of a new form of colonialism’ to Ethiopia, it was ‘just standard operating procedure’ for the IMF (pp. 26-30). In the words of one ex-UN worker, “donors link aid to their own ends” (Browne, 2006). Like so many other state interventions, ODA can take on a life of its own, driven by inertia, ideology and self-interest.

However, this does not mean that there are no success stories. The successful developmental state of South Korea was supported to a considerable extent by aid from the US;

during the 1950s to build an infrastructure that included a nationwide network of primary and secondary schools, modern roads, and a modern communications network. The result was that by 1961, South Korea had a well-educatedyoung work force and a modern infrastructure that provided Park with a solid foundation for economic growth (Savada & Shaw, 1997).

In support of this, according to the ex-director of Development Research at the World Bank, “over the last thirty years it [foreign aid] has added around one percentage point to the annual growth rate of the bottom billion [people in the poorest countries]” (Collier, 2007).

There are other considerable successes. According to the WHO for example, in 2017, “about 85% of infants worldwide (116.2 million infants) received 3 doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP3) vaccine… By 2017, 123 countries had reached at least 90% coverage of DTP3 vaccine” (WHO , 2019). This has increased from 22 percent in 1980. “Vaccine-preventable diseases and neglected tropical diseases registered half (52%) of the total expenditures” (WHO, 2016-7). It is therefore clear that well-targeted public interventions can contribute to development. Even such a strong critic as William Easterly (2007) has admitted that there are success stories citing, “the World Bank in the early 1990s helped fund the Food for Education program to keep Bangladeshi girls in school by giving their parents cash payments in return for school attendance” (p. 151).

Banerjee and Duflo (2011) give a detailed account of the realities of poverty, and show that limited capacity restricts the potential for people to escape. That limited knowledge, or mistaken beliefs, often lead to bad choices is well illustrated by their research. That policy can be driven by ideology rather than empirical evidence is also highlighted. As is the tendency for bureaucratic inertia, whereby policies are maintained even in the face of obvious failure. However, Banerjee and Duflo (2011) give countless examples where a small intervention can have large positive outcomes. For example, the provision of treatment for intestinal worms given to children at school in Kenya over a two-year period resulted in a 20 percent increase in their adult income (p. 272). In the same way as the donors of ODA were once short of private capacity, much of the developing world is now in deficit of this. The donors of ODA can thus provide the necessary injections of capital and capacity, that will increase both public and private sector capacity in the recipient country. This is of course, the stated rationale for providing development assistance to countries overseas.

As outlined by Jeffrey Sachs (2008), key investments in areas such as agriculture, health, education and infrastructure can ‘enable the poor to escape from poverty’ (p. 42). In his book, Common Wealth, he demonstrates that an investment of $245 billion a year, which would be equal to 0.7% of the GNP of OECD states, ‘would be sufficient to close the financing gap’ in foreign aid (Sachs, 2008, p. 245). Paul Collier (2007) identified ‘budget support’ as a potentially effective modality for increasing the amount of ODA that a developing country is able to absorb, although this depends on the capacity of public institutions (p. 101-2). Furthermore, the aid agencies of the OECD donor countries, despite the bad press, have ‘added a whole lot of value to the financial transfer’. Peter Orazem, also concludes that conditional cash transfers for school attendance ‘have consistently increased child attendance’ (Lomborg, 2014, p. 16), while also lowering the poverty rate, among other positive outcomes. It is in such projects as this that donor countries could invest in direct budget support for developing countries. Paul Collier, whilst admitting that technical assistance (for capacity development) is largely donor-driven, does confirm that the potential payoff for increasing technical assistance and thus improving state capacity in countries in transition is potentially very large. Collier (2007) argues that an investment of $1 billion in technical assistance over the first four years of an incipient reform effort would dramatically raise the chances of the reform effort being sustained (p. 114).

Research by John Hoddinott and colleagues has shown that an investment of US$3 billion annually could reduce chronic under-nutrition by 36 percent in developing countries. Such an improvement would improve the prospects for 100 million children (Lomborg, 2014). The Copenhagen Consensus Center, which focuses on finding the most effective interventions recommends a large number of investments in health (deworming children at school, tuberculosis HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis vaccines), agriculture, for example, that could have significant positive results in developing countries. In other words, they have identified what can work. Therefore, while development is not a straightforward process, we know from the success of developmental states that it can be done in a relatively short time-frame, and we also know that ODA can contribute to this process. It should be pointed out that ODA is synonymous with the developmental state. We could rephrase this to say that they are one and the same, or that ODA is a necessary component of the developmental state, and this means that the same concerns apply.

ANTI-DEVELOPMENTAL STATES

Now, while the state is, in a most fundamental way, necessary for the achievement of the previously outlined development and progress, there becomes a point in time when the state is inclined to act against the pursuit of such goals. This is because a higher level of state involvement in the economy can far outweigh the costs only in the earlier stages of economic development, i.e. industrialization. There becomes a point at which ever-broader and ever-deeper interventions become anti-developmental. The state will always and everywhere pursue this, to varying degrees.

A negative impact of excessive state intervention is aptly summed up by the following quote from Leonid Brezhnev, the leader of the Soviet Union from 1964 until 1982. He stated that the Soviet enterprise managers shy away from innovation ‘as the devil shies away from incense’ (Kuran, 1987). As we know beyond doubt, it is innovation that drives development. It was the high level of coercion that undermined the productive potential of cooperation. The Soviet Union became fundamentally anti-development, as shown by its ultimate collapse. However, this is an extreme case of state intervention, and we should perhaps turn our attention to what have become the more mundane interventions of the so-called capitalist liberal democracies.

Before doing so, it should be pointed out that any kind of social intervention is extremely difficult, and it is hence highly unlikely that the state will be able to achieve the desired outcome. More importantly, any state intervention will always have negative impacts, and these may far outweigh the intended positive ones. It seems self-evident that caution is the only responsible approach. There are so many of these negative impacts, but Tomas Sowell (2015), for example, points out that rent control laws in the US, while purporting to be for the benefit of low income families, incentivizes dishonest behavior on the part of landlords and tenants alike (p. 407-8). It cannot be the case that a state intervention that results in incentivizing dishonest behavior can be regarded as a minor cost.

It is also true that, because of our democratic political system, politicians are likely to pursue short-term goals that appeal to certain voter groups. Entitlement programs, which give a privilege to a certain group, are a good example of this. These programs inevitably balloon in cost, as other citizens are drawn to the entitlement. The Welfare State in Britain has many examples of such entitlements. In the immediate post-WWII period, just 3.4 percent of the population received means-tested benefits. Remarkably, despite the dramatic increase in wealth in the UK since then, 29 percent of the population now receive means-tested welfare benefits. According to a 2012 study, 20 percent of working age households in the UK contain one generation that is not working. Furthermore, one-percent (about 15,000 households) has two generations who are not working. Of this one-percent, almost 10 percent have never worked, and over one-third have not worked in the last five years (The Guardian, 6 April 2013). Whilst there are complex reasons for this, it must be the case that welfare programs have a strong tendency to de-incentivize recipients to work, and this limits their ability for progress. It is implausible to suggest that being out of work, long-term, is conducive to individual progress and development. It is also contrary to the interdependent goals of freedom and capacity on which development depends, and hence becomes anti-developmental. In the UK, one-sixth of children are functionally illiterate (Bartholomew, 2016), and this is despite a public education budget of about £90 billion in 2017–18 (11 percent of public spending, and 4.3 percent of national income). Shockingly, while the Flynn Effect predicts a steady increase in cognitive ability, there seems to be data that shows that IQ scores have actually declined among teenagers since the 1970s (Flynn, 2009). It seems clear that public education is failing to realize the twin goals of freedom and capacity that underpin development and progress. In light of such failures, it is not possible to automatically assume that the provision of mass education is an obligatory state function.

While it is deemed necessary to provide public support for certain targeted industries under the developmental state model, there are high costs to this. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “policy-induced transfers to agricultural sectors of 51 countries…” total USD 620 billion (EUR 556 billion) a year (average 2015-17). The OECD admits that, “most agricultural policies in place today are not well-aligned with shared objectives for the sector: to increase productivity sustainably, enhance environmental performance, and improve farmers’ ability” (OECD, 2018). Subsidies such as these result in high prices for domestic consumers, and when the inevitable excess production is sold on world markets at low prices, it drives down the price received by producers in developing countries. In Japan, over 40 percent of gross farm receipts come from public subsidies. Over the last 50 years the food self-sufficiency rate (calorie-based) fell from over 70 percent to less than 40 percent (Jiji, 2017). It is indisputable that the market has been severely distorted by the intervention of the state, and that resources are being misallocated.

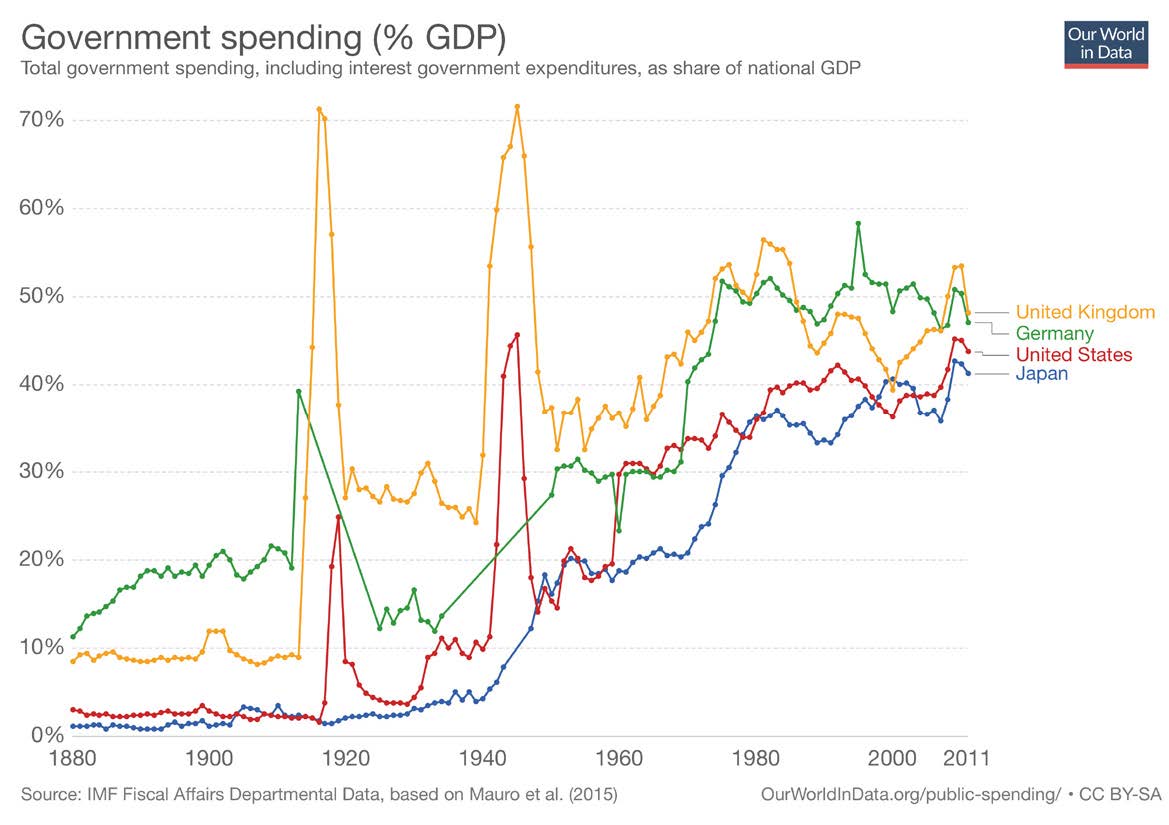

All this public spending has one inevitable result: debt. Almost all industrialized states run their national budgets in deficit, constantly. Of the 34 OECD member states, all have considerable debt. Only seven have a level of debt that is below 50 percent of GDP. Twelve have public debts that are over 100 percent of GDP, and Japan has a level of public debt that is 237 percent of GDP. This means that these states then have to use a large portion of their yearly budgets just paying back their debt. In the case of Japan, 25 percent of government spending is on servicing its debt, with 10 percent being paid in interest payments alone. In the UK, 6.5 percent of government spending is just on debt interest. This raises the inevitable questions of whether such a situation is sustainable in the long run, and whether such a trend is evidence of anti-development?

In addition to the aforementioned subsidies and inevitable public debt, there are other much more serious implications of state interventions in the economy, beyond the most basic regulatory functions. Kiyoshi Kurokawa, Chairman of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission called the Fukushi- ma Nuclear Accident, ‘a profoundly manmade disaster’. Directly citing the overly cozy relationship between regulators and private operators, Kurokawa also criticized the public institutions in which, “regulation was entrusted to the same government bureaucracy responsible for its promotion”. The result of this was that, “bureaucrats put organizational interests ahead of their paramount duty to protect public safety” (The National Diet of Japan Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission), and it is to this issue that we now turn.

Figure 4. Ever-increasing government spending.

We can see from Figure 4, which shows the dramatic increase in government spending as a percentage of GDP over the last 150 years, that the state has increased dramatically in size. It is an intrinsic, ever-present feature of the state, and is the ultimate paradox of human social organization. The German sociologist Robert Michels called this the Iron Law of Oligarchy. He argued that all institutions, even democratic ones, will inevitably become oligarchies because, “the principal cause of oligarchy… …is to be found in the technical indispensability of leadership” (Michels, p. 417). Furthermore, the institutions created by society will inevitably tend towards self-interest and self-preservation, ‘from a means, organization becomes an end,’ and “the sole occupation [of the institution] is to avoid anything which may clog the machinery”(Michels, p. 390). It is therefore irrational to think that institutions, particularly those of the state, will voluntarily disband when they have achieved their original function.

Therefore, we have a recognition that the State is always and everywhere necessary, and is especially necessary in the earlier stages of industrialization, but that it will, by and of itself, grow beyond, and perhaps far beyond, the primary functions for which it is best suited: its niche perhaps. Consequently, whilst we have concluded that the state is a necessary institution for improving the well-being of humans, we have also paradoxically concluded that there are considerable dangers, dilemmas and inefficiencies that result from empowering an institution with ultimate authority. In this way, “the study of human institutions is always a search for the most tolerable imperfections” (Epstein, 2008).

If we follow this logic, then the only conclusion to reach is that state involvement in the economy over time should look like a pyramid (Figure 5). It rises dramatically during periods of early development, it peaks at industrialization or early post-industrialization, and then it reduces over time to a very low level. However, and indeed the crux of the issue, it is implausible to think that public institutions will voluntarily dissolve themselves, and this is even more likely if the institution in question has been successful. So, if we think it is necessary for the state to cut back on its activities, how would we achieve such a thing?

TOWARDS A NEW INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENTAL STATE

The work of the developmental state in OECD countries is, to varying degrees, basically almost finished. They have provided levels of equal opportunity that have never been achieved before in the history of mankind. But, the state has, in too many cases, far overstepped its most effective spheres of activity, and can thus be characterized in many ways as anti-developmental. It seems therefore, that the only conclusion to reach is that the state must be reduced dramatically in size and scope, and that, in the successful developmental states, this is now an achievable, and desirable, goal.

What follows is a very brief outline of how this process may look. As the state functions are reduced domestically in the OECD states, functional activities are transferred overseas in the form of ODA. This means that the OECD states transfer functional activities overseas, for a limited time, to make investments in developing countries. These investments are slowly scaled-back as conditions necessitate, meaning that they are short- to medium-term investments. Such activities will include investments in transportation, health and education infrastructure for which developmental states have considerable expertise. This would include building state capacity in the recipient country to provide for the basic state functions of internal law and order and national security, as well as the state capacity necessary to create inclusive institutions. Figure 5 is an infographic illustration of this process. In this process the size of the state in OECD countries reduces slowly, even though public spending and activity is reduced domestically, some of its operations are transferred overseas. Within the various government ministries of OECD states, the international cooperation departments can be increased in size, and collaborations with ministries overseas with similar functions can be expanded. This would facilitate capacity building in public institutions in recipient countries.

Figure 5. Towards a new international developmental state.

Importantly, this international cooperation must include exit plans, or goals. The aforementioned end goal for the OECD countries is, the medium- to long-term dramatic reduction in the size of the state; a considerable reduction in the level of state interventions in society and the economy. The exit plan for ODA is, after an initial increase, the medium-term reduction in ODA spending as a component of the overall reduction in the state activities of donors. The end goal for the developing countries, following the initial increase in state capacity and resulting industrialization, is the medium- to long-term reduction in the size of the state, following the OECD countries.

There are enormous potential benefits to such a process. An increase in such international cooperation could potentially foster international peace because of the mutual dependence it builds. This is a basic premise of the International Relations theory of Liberalism. In the OECD countries, a reduction in the size of public spending would reduce the levels of public debt. It must surely be the case that reducing the size of public debt is a positive move; at the very least, it will reduce government spending necessary to meet debt obligations. Furthermore, a reduction in the size of the state will reduce the high levels of misallocation of resources that results from not allocating resources according to market principles. A reduction in welfare spending will reduce welfare dependency, and increase the potential for development as defined by capacity and freedom.

The advantage of this approach to scaling back state operations through the increased provision of ODA is that the reduction of the state would be a relatively slow, yet systematic process. State functions are determined by the place of the country on the development ladder, and not by political ideology. Essentially, the states further up the ladder transfer operations down the ladder, thus facilitating faster progress up the ladder. It avoids the shocks of neoliberal economics, by utilizing the capacity of state institutions and merely changing the location of their operations. As the developing countries industrialize, the donor countries can slowly scale back their operations, thus reducing the size of their state, over the medium-term.

It is the case that the state has weakened itself through its propensity towards continual expansion. A reduction in the plethora of state activities would enable the state to focus on its core functions of security and regulation. These functions underpin all others and the state must be able to perform these to a high degree. The military power of the West, and in particular the United States, has been a key factor in enabling the post-WWII successes in international development. Whilst not ignoring the disappointing fact that this military power has sometimes been utilized for illiberal pursuits, it is an essential component of the West’s ability to preserve the international system that is the bedrock of international development. In this way, it is necessary to protect the progress we have made so far. Furthermore, the Soft Power of the West is fundamentally about values, and these are the values of freedom, and equality of opportunity, both of which are manifested in democracy and capitalism.

CONCLUSION

If the Liberal Democracies are to maintain, or regain their liberalism (which they must), and if international development is to continue in the face of considerable and diverse challenges, then our states must be strong and focused. The underpinnings of the global political and economic order, that which has brought forth the afore- mentioned dramatic improvement in human well-being, are the values of individual and collective sovereignty (freedom/responsibility), and the creation of institutions that unlock the enormous potential of human reason. These are fundamentally human values, stemming from biological evolution and the axiom that humans are social animals. These values were not made in the West, but were only first clearly enunciated there.

As international developmental states, the early industrializers and the later industrializers of the OECD thus become the facilitators of global development, whilst at the same time cutting back their own domestic activities, facilitating further progress at home. ODA becomes the mechanism through which the states of the OECD slowly transfer their operations overseas, as a part of the process of reducing their size. It would only strengthen these states, and not weaken them.

Therefore, we have in our sights two joint, mutually reinforcing goals of global economic development. In the developing world, the final and complete eradication of extreme poverty, the concurrent complete provision of state-instituted domestic law and order, followed by industrialization, increases in income, progress in education, health and other measure of social development. In the industrialized world, the state can slowly withdraw from interference in the economy, thus facilitating private freedom and capacity, leading to enhanced progress at home. As such, the successful developmental states can veer away from anti-developmentalism, and refocus on their own further development, through capacity and freedom.

REFERENCES

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2013). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. London: Profile Books.

Banerjee, A.V. & Duflo, E. (2011). Poor economics: A radical rethinking of the way to fight global poverty. New York: Public Affairs.

Bartholomew, J. (2016). The welfare of nations. Washington: Cato Institute. Browne, S. (2006). Aid and influence: Do donors help or hinder? London: Earthscan.

Collier, P. (2007). The bottom billion: Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chibber, V. (2014). The developmental state in retrospect and prospect: Lessons from India and South Korea, chapter 2 in Williams, M. (Ed). The end of the developmental state? New York: Routledge.

Easterly, W. (2007). The white man’s burden: Why the west’s efforts to aid the rest have done so much ill and so little good. New York: Penguin.

Epstein, R.A. (2008). Overdose: How excessive government regulation stifles pharmaceutical innovation. New haven: Yale University Press.

Flynn, J.R. (2009). Requiem for nutrition as the cause of IQ gains: Raven’s gains in Britain 1938–2008, Economics & Human Biology, 7(1), 18-27.

Hayek, F.A. (1960). The constitution of liberty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hayter, T. (1971). Aid as imperialism. London: Pelican Books.

Industrial Structure Council. (1975). Japan’s industrial structure: A long range vision. Tokyo: JETRO.

Jiji. (2017). Nation’s food self-sufficiency rate hits 23-year low as rice consumption decline continues. The Japan Times. Retrieved from https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2017/08/10/business/japans- food- self- sufficiency- rate- hits- 23- year- low- rice- consumption-decline-continues/#.XOvk7S2B2F0.

Johnson, C. (1982). MITI and the Japanese miracle: The growth of industrial policy, 1925-1975. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Kuran, T. (1987). Preference falsification, policy continuity and collective conservatism. The Economic Journal, 97(387), 642-665.

Kurokawa, K. (2012). The national diet of Japan Fukushima nuclear accident independent investigation commission. Tokyo: The National Diet of Japan.

Locke, J. (1764). The two treaties of civil government. Thomas Hollis ed. London: A. Millar et al., Retrieved from https://oll.libertyfund. org/titles/222.

Lomborg, B. (2014). How to spend 75 billion to make the world a better place. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Consensus Center.

Mill, J. S. (1977). The collected works of John Stuart Mill, volume XIX - essays on politics and society part 2 (considerations on rep. govt.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Moyo, D. (2009). Dead aid: Why aid is not working and how there is another way for Africa. New York: Penguin Books.

The White House, Office of the Press Secretary. (2016). Remarks by the president at Howard University commencement ceremony. Retrieved from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/ the-press-office/2016/05/07/remarks-president-howard- university-commencement-ceremony.

OECD (2018), Agricultural policy monitoring and evaluation 2018. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Pinker, S. (2011). The better angels of our nature: Why violence has declined. New York: Viking.

Rosling, H. (2018). Factfulness: Ten Reasons we’re wrong about the world- and why things are better than you think. London: Scepter.

Sachs, J. (2008). Common wealth: Economics for a crowded planet. New York: Penguin.

Savada, A.M., & Shaw, W. (Eds). (1997). South Korea: A Country Study (Area Handbook Series) 4th Edition. Washington: Library of Congress Federal Research Division.

Sen, A. (2000). Development as freedom. New York: Anchor Books.

Smith, A. (2007). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. Edited by S. M. Soares. MetaLibri Digital Library.

Sowell, T. (2015). Basic economics: A common sense guide to the economy. New York : Basic Books.

Stiglitz, J. (2002). Globalization and its discontents. London: Penguin.

The Guardian. (2013, April 6). Benefits in Britain: separating the facts from the fiction. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2013/apr/06/welfare-britain-facts-myths.

The World Bank. (1997). The state in a changing world. London: Oxford University Press.

WHO. Results report programme budget 2016-2017. Retrieved from https:// www.who.int/about/finances-accountability/budget-portal/rr_2016-17.pdf?ua=1.

. (2018, July 16). Immunization coverage. Retrieved from https:// www.who.int /en/news-room/fact -sheet s/det ail/immunization-coverage.