ABSTRACT

With the development of tourism in Jiuzhaigou, China, some performers from other Tibetan areas in China have been the important symbol carriers and spokespersons. This study explores the changing process of Tibetan culture in tourism from ‘authenticity of life’ to ‘authenticity of performance’, including the feedback reaction from ‘authenticity of per- formance’ to ‘authenticity of life’. For the performers in Jiuzhaigou, cultural authenticity in the context of tourism relates more to a new sense of life and the reconstruction of a sense of place, which mainly originate from individual professional achievement and the enhancement of self-identity for the perform- ers, as representatives of ‘The Host’ in the tourist destination.

Keywords: Performers, Authenticity of life, Authenticity of performance, Jiuzhaigou

INTRODUCTION

The social and cultural impact of tourism has been widely discussed in the tourism literature, with the relationship between cultural com- mercialization and cultural authen- ticity receiving frequent attention. in the modern tourism context, some phenomena have begun to be ques- tioned, such as: is traditional culture becoming overly commercialized? Do visitors see an authentic repre- sentation of local culture in a tourist destination? is the culture created by local people original or only a perfor- mance? in addressing these problems, Goffman (1959) proposed his famous Front-Back Stage theory in the field of sociology. Goffman likened one’s life to a big stage, on which one’s ordi- nary life is a staged performance and different behavioral presentations and social roles could be found through the discrimination of the Front-Stage and Back-Stage. Based on Goffman (1959), maccannell (1973) defined what visitors see at the front-stage of a tourist destination as ‘staged authen- ticity’; the activities and settings in a tourist destination designed especially for tourists reflect only the establish- ment and customization by tourism planners. maccannell’s hypothesis suggests that tourists are eager to seek authenticity, but what host commu- nities offer is not primarily authentic. maccannell’s (1973) concerns triggered more debate. cohen (1988) argued that authenticity in tourism is determined by what people feel, and could not be confined to ‘original’ things. Thus, authenticity in tourism could be transferred and created. cohen expressed a more flexible view of authenticity in tourism, and offered us a wider thinking space.

Inspired by cohen’s approach, this article tries to reveal, from the perspective of cultural authenticity, the process through which ethnic traditional culture in a tourist destina- tion changes from back-stage to front- stage, and the corresponding feedback reaction from front-stage to back- stage. in other words, it examines the process in which ‘authenticity of life’ changes to ‘authenticity of perfor- mance’, and the process of feedback from ‘authenticity of performance’ to ‘authenticity of life’. We propose that cultural authenticity in tourism is more relevant to the reconstruction of cultural identity and the re-shaping of place attachment to a tourist des- tination, by analyzing an example of cultural brokers as performers in the Jiuzhaigou region of china. Further, we show that tourism development in Jiuzhaigou has influenced eth- nic traditional culture far beyond a ‘Front-Stage’ interpretation.

DISCUSSION

The performers in Jiuzhaigou, China Jiuzhaigou is located in the north- west of the Tibetan and Qiang Au- tonomous Prefecture in A-ba, Sichuan Province, china. it is a World Natural Heritage Site and popular tourist destination. A-ba is the second largest Tibetan region and the largest Qiang residential area in china. Perform- ing groups demonstrating Tibetan and Qiang culture first appeared in Jiuzhaigou in 1984, when tourism began to develop there. These groups have been established and funded mostly by enterprises and investors from outside Jiuzhaigou. currently, eight cultural groups – including ‘Highland Red’, ‘Tibetan mystery’, ‘Lotus Flowers’, and ‘Paradise in Jiu- zhaigou’ – perform especially for the tourists that are scattered in the many restaurants and hotels in the area. in Jiuzhaigou, the performers in these groups have become the symbolic carriers of Tibetan traditional culture, and the brokers between tradition- al Tibetan and Qiang culture and tourists, rather than the Tibetan and Qiang indigenous populations.

There are 758 performers, includ-ing Tibetans (66%), Qiangs (23%), Hans, and others, in the eight art groups in Jiuzhaigou. Nearly all of the performers come from outside Jiuzhaigou, including Ganzi, Ganshu, Qinghai, and Tibet. As such, outsi- ders have displaced the local Tibetan residents of Jiuzhaigou as its cultural carriers and brokers.

Most of the performers are young (average age of about 20 years) and have a pleasing image; they have per- fect figures and the looks to meet the aesthetic need of tourists. Strictly speaking, these young performers do not represent the whole of Tibetan culture, but instead demonstrate and display it through cultural perfor- mances for tourists. These performers moved to Jiuzhaigou, staying in the native Tibetan cultural areas and shap- ing their own traditional lifestyles, behavior, institutions, psychology, and religion year after year. From the perspective of cultural theory, they belong to one stable group that has a shared composition, language, customs, mental character, and reli- gion. Thus, they can be viewed as the carriers of Tibetan traditional culture, and the brokers between the tourist destination and the tourists.

The change process from ‘authen- ticity of life’ to ‘authenticity of per- formance’

The anthropology of tourism usually interprets the relationship of host-guest as the interaction between the host community as ‘the other’ and tourists as ‘self ’. However, the meaning of ‘the other’ in Jiuzhaigou seems much more complex than in other places. To derive economic benefits from tourism, certain for- eign investors have occupied the dis- course of power in expressing Tibetan traditional culture, while the local Tibetan people in Jiuzhaigou have been excluded from these cultural expressions. With the development of tourism, the investors have employed a large number of performers from different ethnic cultural contexts as spokespersons of Tibetan and Qiang cultures. Thus, these performers play the role of ‘the other’ on the front- stage in Jiuzhaigou, instead of local Tibetan residents. Before coming to Jiuzhaigou, some of these perform- ers were farmers and herdsmen in their home areas; others were migrant workers, itinerants, artists, and em- ployees or students trained by several art schools.

To cater for the mass tourism market in Jiuzhaigou, it is has been necessary to construct and present ethnic culture in terms of symbolic production. During this process, the performers are subject to these sym- bolic demands, and they change their original modes of cultural life to meet the agreements that they have made with their investors and managers. meanwhile, with this constant par- ticipation and symbolic creation in the context of tourism, the original ‘authenticity of life’ of the perform- ers is changed, becoming a sort of ‘authenticity of performance’ mixed with objective authenticity, constructed authenticity, post-modern authen- ticity, and so on. Subsequently, these changes in their modes of life are the manifestation of their cultural adjustment and the reflection of the process in which they reconstruct their cultural identity and their new place of attachment.

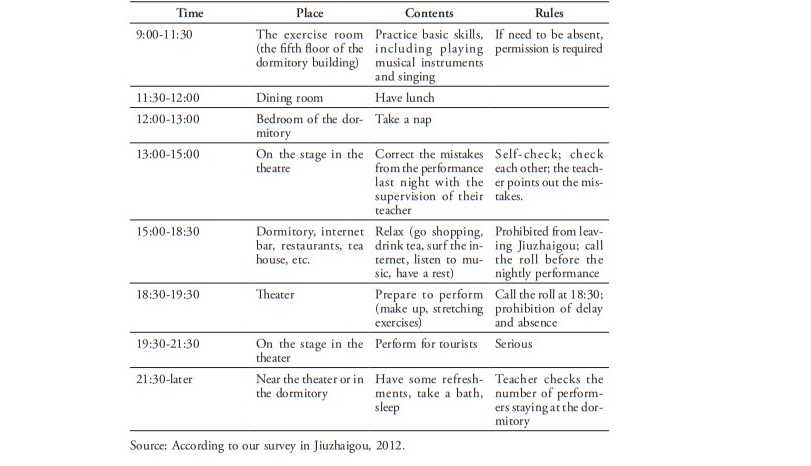

Changes in lifestyle. Before the performers came to Jiuzhaigou, they had different lifestyles. When they come to Jiuzhaigou, they became employees in tourism performing enterprises by signing a legal contract with their employers. As a result, their lifestyle has been changed from relatively free to one that is ordered and uniform. As an example, a daily schedule of the ‘Tibetan mystery’ group is shown in Table 1.

In general, the daily schedule of performers in the other art groups is similar. For the aesthetic needs of tourists and the convenience of unified training, the managers also required performers to learn the Han language, especially mandarin, a language different from Tibetan, but common among mass tourists in china. moreover, the managers also required the performers to understand Tibetan traditional culture, especial- ly Tibetan palace art, folk art, and temple art. When we interviewed some non-Tibetan performers about their need to learn about Tibetan traditional culture, they all answered us positively, but this has to be quali- fied in that even if they are Tibetans, they do not need to grasp Tibetan knowledge completely. in fact, the performers paid more attention to their own interests in their daily lives than to acquiring collective know- ledge about the traditional culture of the ethnic group. Therefore, this experience in the art group helps them reconstruct their understanding of Tibetan culture. in addition, during their stage rehearsals, the producers of cultural programs required them to change what they had learned about singing and dancing as children or in their home areas, in that they had to add new skills about the art of performance. it not only created an opportunity for the performers to integrate different elements of Tibetan culture, but also changed and reshaped their consciousness and cognition of the ethnic group as ‘self ’ in the traditional world, in contrast to ‘the other’ in modern society. There- fore, the whole process is essentially the deconstruction of ‘the traditional’ understanding of themselves, and the reconstruction of ‘the new’ consciousness of themselves under the gaze of tourists.

Table 1. Daily schedule of the performers in the ‘Tibetan mystery’ group.

Besides the changes brought on by their rehearsals and stage performances, their cultural horizons broaden day-by-day, significantly changing their leisure habits. in comparing their performance costumes for the stage with their ordinary dress in daily life, the function of traditional clothes has changed from daily necessities to performance tools. To see traditional clothes, one now has to go to the theater or wait until festival time. After leaving the stage, the actors don the same clothes as the young men in modern society, such as t-shirts, jeans, and gym shoes; the actresses prefer to wear one-piece dresses, short pants, and high-heeled shoes. As for their diets, they partook of typical Sichuan cuisine, instead of their traditional Tibetan diets, such as Zanba, buttered tea, beef, and mutton. in their spare time, they did not drive cows and goats on the grassland as before, but played online games, purchased cosmetics, and listened to popular music. of course, some of the Tibetan performers retained their own ethnic recreational habits, like playing Tibetan music and instruments. The changes in recreation clearly reveal that the cultural authenticity presented for tourists is only a kind of symbolic production and staged authenticity. The lifestyle of the Tibetan performers at the back of the stage more closely resembles the modern lifestyle. Thus, the division between ‘life authenticity’ and ‘staged authenticity’ is blurred. The real lifestyle of the performers at the back of the stage is just the way the modern tourists want to see it, and the staged authenticity is only a cultural production for mass tourists. The staged authenticity has become the foundation for maintaining the new authenticity of life. Here, ‘the authenticity of life’ and ‘the authenticity of performance’ constitute a collusive game. To coordinate with the game, the performers have changed their lifestyles to complete the cooperation of ‘self ’ and ‘the other’.

Changes in interpersonal communication. With the development of tourism in Jiuzhaigou, the performers have more opportunities to interact with other people in various cultural contexts, including tourists from all over the world, business- people, colleagues in the eight art groups, and tour guides from many travel agencies. During the process of communicating with these people, the performers are affected by them, and learn some practices and values from modern society.

When they work in Jiuzhaigou, the performers are most frequently in touch with their teachers and colleagues. on the one hand, they still retain the traditional rules of inter-personal communication, including respecting their teachers, depending on their acquaintances, paying attention to their family, and so on. on the other hand, they learn new practices and principles, including those of market exchange, respecting one’s privacy, and cooperating with non-Tibetan people. For example, some per- formers worked in their spare time by cooperating with tour guides to show tourists around Jiuzhaigou. Some performers with savings even learned to trade in stocks. Some of them started to share their business practices with their relatives and friends. They have learned to protect their own interests through the legal system. For example, one of the performers thought his salary unreasonable, but his contract with his employer was not yet due for renewal. He tried to negotiate with the employer and, after the negotiation failed, consulted a lawyer.

When some of them were invited to perform in other cities and countries, their opportunities to interact with famous stars, directors, brokers, and investors expanded. Their interpersonal range has been broadened greatly and their view on life has become more long-term and more subject to planning. of course, some performers began to recognize the importance of interpersonal communication and learned to utilize it to achieve his (or her) goals. A few even learned to create more opportunities for individual development. For example, Wangmu, an actress with a good image and excellent performing skills, realized her own competitive advantage in modern society after she was invited to perform outside Jiuzhaigou. That is, she could use her unique ethnic identity and art skills to occupy some place in the modern world. Encouraged by a director, she enrolled in a popular TV show designed to select excellent performers; she came first in china. She became well known and prepared to study at the central Academy of Drama in china, china’s best university in the field of performing arts. With the performers, there are many examples like this. These changes in interpersonal communication have gradually altered the performers’ thinking.

Changes in psychological emotions. Before coming to Jiuzhaigou, the performers’ surroundings were mainly confined to their hometown, usually a farm or village. From the perspective of cultural theory, they were fostered in a pastoral and farming culture, which generated a psychology of stability seeking, romance, and freedom, and to be pure, free, and safe. However, with the change in their lifestyle, they were introduced to new information that influenced their original psychological emotions. Some kept their rural-based emotions, but others changed. For example, before arriving in Jiuzhaigou, an actor in the ‘Tibetan mystery’ art group had no future plans. As he said: “For my life plan? No, i didn’t have it before. When i lived in my hometown, i had no plans for my future, as i like the feeling of freedom”. However, after moving to Jiuzhaigou as a performer, the teachers and managers provided training in vocational skills development and career planning, and he began to plan for his future. His experience in Jiuzhaigou has changed his undisciplined character; he now has a greater concept of time and is learning to plan his future life rationally. Also as he said:

Now I am not an eagle on the grassland, I can’t be in the state of not planning for my life. I must learn how to plan my future life efficiently and meaningfully. Of course, I need to know how to realize my dream step-by-step. Time is very precious for me.

We found that this actor had not only developed the concept of time, but also the commitment to further planning to improve his own professional skills and financial ability. A more modern psychological emotion has become rooted in his mind.

in addition, the performers appeared more tolerant and adaptable than before coming to Jiuzhaigou. To meet tourists’ needs, the performers from different areas must move out of their real identity and adopt one unified role as ‘Tibetans’ in the tourist arena, becoming more tolerant in the process.

Changes in religious beliefs. The Tibetan people in china follow Tibetan Buddhism. most Tibetan performers in Jiuzhaigou retained their pious religious beliefs. How- ever, for some, their religious beliefs diminished and they turned increasingly to the worship of money. With the rapid development of tourism in Jiuzhaigou, some Tibetan performers from the remote and poor regions of West china saw more and more market transactions, and experienced the advantages of wealth accumulation. Particularly when making friends with tour guides from modern society in Jiuzhaigou, they were introduced to new ideas and opportunities about how to make more money. They tried to expand their money-earning opportunities beyond their job as a performer. Some performers used their free time to rent a car to show tourists around Jiuzhaigou, as both a tour guide and driver. others sold Tibetan decorations to tourists. They were no longer satisfied with the role of being performers, and their beliefs in Buddhism changed. Yet, their declining Buddhist faith seems hypocritical, in that they hoped to earn more money with the help of the Buddha. For example, in the ‘Gao Yuanhong’ art group, an actress and her husband bought a new car to conduct business in their spare time. in their room in Jiuzhaigou, we were surprised to see offerings of money, rather than the traditional Tibetan butter lamp. When asked why, they pointed at the picture of a Tibetan religious leader on the wall and answered with a laugh: “we hope [he] bless[es] us to make more money in the future”.

However, only a small number of performers lost their pious religious beliefs in the process of tourism development; most performers either retained, or even enhanced, their traditional religious beliefs. The main reason for this was the power of tradition and the reappearance and reconstruction of the cultural atmosphere of Tibetan Buddhism. These influences varied by art group, however. For example, in the ‘Gao Yuanhong’ art group, the program designers showed more interest in the material culture of Tibetans, such as Tibetan singing and dancing, dress show, and games with tourists. its performers were affected day-by-day, and cared little about Tibetan religious culture. in contrast, the program designers in the ‘Tibetan mystery’ art group focused on presenting Tibetan Buddhist culture, and this enhanced their religious beliefs. more than before, they were presented with the beauty and mystery of Tibet- an Buddhism culture. Furthermore, the program is so popular among tourists, that the performers have grown more interested in and gained a better understanding of their own religious culture.

The process through which these Tibetan performers’ changed from ‘authenticity of life’ to ‘authenticity of performance’ provided more opportunities to absorb a new cultural gene and adapt to new surroundings, whether active or passive. During this process, the performers needed to change themselves constantly, and make choices between traditional and modern culture. Although everyone is different, most performers reconstructed themselves and re-discovered something about their own ethnic culture and themselves, reshaping their ethnic identity. meanwhile, the change in themselves at the tourist destination provided more opportunities and a wider space of self-fulfillment, including self-esteem, self-efficacy, self-confidence, and self-discovery, bringing something new to their sense of self-identity and reshaping the new place attachment to the tourist destination.

The feedback process from ‘authenticity of performance’ to ‘authenticity of life’

Not only does the change from ‘authenticity of life’ to ‘authenticity of performance’ reflect processes of change in Tibetan traditional culture, but also the feedback process from the ‘authenticity of performance’ to ‘authenticity of life’ reflects the reaction and result of the change process in Tibetan traditional culture.

During the winter, from November to April, few tourists visit Jiuzhaigou. The Tibetan performers in Jiuzhaigou are given a holiday, and most return to their hometowns. From the perspective of culture, their hometowns belong to the original areas of Tibetan traditional culture. When the performers return to their hometown, they bring with them the new cultural gene acquired in Jiuzhaigou; this gene integrates with the original cultural gene to promote cultural change. This cultural process of reaction from ‘staged authenticity’ to ‘life authenticity’ occurs quietly.

Feedback of material culture. in cultural theory, the conception of culture is usually divided into three parts:

material, behavioral, and mental. First, from the perspective of material culture, the reaction of the cultural process from ‘staged authenticity’ to ‘life authenticity’ mainly occurs at this level, including dress, hairstyle, and cuisine. For example, an actress in the ‘Tibetan mystery’ group from Yushu, Qinghai Province had grown used to wearing modern dress in Jiuzhaigou, like long skirts and leggings in South Korean style. When she returned to her hometown, she continued to wear the same. According to her,

When I appeared at the entrance of our village, many girls and women who grew up with me in my childhood came around me and saw my dress curiously and admiringly. What’s more, they asked me where I bought my dress.

After she told them that she bought the dress on the internet, some of the young girls begged her to teach them how to do the same. She was pleased to teach them how to buy modern dress and fashionable cosmetics. moreover, she was asked to teach them new makeup skills and how to protect their skin. When she returned to her hometown the following year, she encountered more young girls and women wearing South Korean style dresses and using fashionable cosmetics. Some of the young girls had even become agents of famous cosmetic brands, like mary Kay and Lancome. These changing roles in the extended family also brought them more self-esteem and self-efficacy.

The performers also brought Sichuan cuisine back to their home- towns. Living in Jiuzhaigou, the performers grew used to eating its spicy Sichuan food. if no Sichuan cuisine was available in their hometown, they cooked it themselves. Their relatives and friends became curious, and wanted to learn how to cook the same. Several performers from the same region, along with their Tibetan relatives, wanted to open a restaurant with Sichuan cuisine in their hometown to make money. After some of the relatives learned how to cook Sichuan food from the performers, they decided to integrate the Sichuan style into their Tibetan traditional food, and tried to produce creative food and recipes.

Feedback of behavioral culture. In the remote Tibetan regions of china, most farmers and herdsmen are still affected by the traditional farming and pastoral culture, and they prefer a free and casual life. Their life appears unplanned and happy-go-lucky. However, with the performers from Jiuzhaigou bringing new ideas back home, the behavioral character of Tibetan residents began to change substantially, one of the most prominent examples of which is wealth management.

In modern society, wealth management is the most important element in the daily life of many people. How- ever, for the traditional farmers and herdsmen in the Tibetan regions, wealth management is far removed from them. However, the performers brought their newly acquired wealth-management skills home with them, teaching them to their relatives and friends. As a result, some residents learned new ways of making money and even accumulated extra wealth for their family. For example, a Tibetan performer in Jiuzhaigou, Ge sang from the Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Ganan, said:

I came to Jiuzhaigou as a per- former in 2008. In my spare time, I recognized a tour guide and became good friends. He was very interested in playing the market with his spare money. Influenced by him, I learned to do some wealth-management activity in my spare time, such as purchasing funds, trading gold, foreign exchange, and so on. I found it is a good way to make money rapidly and efficiently. In the winter of 2010, when I had my holiday in my hometown, some relatives and friends got to know the story of my financial transactions. They wanted to learn these skills. To get them to learn these ways more quickly and accurately, I introduced the tour guide to them. Later, my relatives kept in touch with the tour guide and learned the skills of managing their wealth. In the end, my relatives bought some houses in the city with their earnings. Inspired by them, more villagers wanted to learn these skills. To meet their needs, my relatives especially went to our county town to buy two computers and opened a network to help these residents grasp these skills to make money. Under their leadership, the members built a chat group on QQ called ‘Biexia’ (meaning money in Tibetan) from the Zha-nang village in order to transfer new information on investment and wealth-management at any time. You can see, how strong the ideas that they want to make money is!

The performers have brought the ideas of time management, market exchange, and individual image shaping back to their hometowns, which has gradually changed local behavior.

Feedback of mental culture. As the performers paid more attention to the development of their future careers and individual achievement, they recognized the importance of planning their careers, shaping their images, and time management. in short, they became concerned more about the realization of individual value. However, this is contrary to their traditional concept of collectivism. With their return to the original Tibetan cultural areas, this new mental cultural change and approach was incorporated into traditional Tibetan culture. many performers reported affecting their younger siblings with the new concept of individualism.

For example, ci ren zhuo dan, an actor in the ‘Jiuzhai Paradise’ group, was a herdsman in his hometown. Before coming to Jiuzhaigou, he had never left his village. He failed his first interviews in Jiuzhaigou, eventually landing a job as a Tibetan performer. He then thought about the importance of how to improve his employment skills and design an individual image. When he returned to his hometown, he told his younger siblings, still in high school, about the importance and meaning of improving individual value, including how to dress moderately, express oneself smoothly, and display oneself outstandingly. When he saw that one of his brothers did not cherish his time, he tried to persuade him to recognize the importance of time management, as ci ren zhuo dan was required to follow a strict schedule in Jiuzhaigou, and he usually used his free time to practice his performing skills to improve his competitive advantage. According to his own experience in Jiuzhaigou, he hoped his family would embrace the modern idea of individual competition. His family in his hometown was used to being together. if one of the family members encountered a problem, he would first approach his family for help, before even trying to depend on himself. However, ci ren zhuo dan felt that his hometown family in the Tibetan cultural area should adapt themselves to the rules of modern society.

This emphasis on individual values reflects the Tibetan’s ability to adapt culturally. However, it runs counter to their traditional Tibetan Buddhism that focuses on others and collective benefits, not the individual. if these cultural changes are not controlled, they will lead to a decline in traditional religious faith. As mentioned before, one performer lost her religious beliefs as she focused more on her personal interests. Similarly, when the performers’ hometown families pay increasing attention to the realization of individual value and benefit, then perhaps their pious religious beliefs will weaken, leading to future conflict.

CONCLUSION

From a cultural perspective, the performers in Jiuzhaigou are the im- portant symbol carriers and spokes- persons. They replaced the local resi- dents to become the ‘cultural Host’ in a tourist destination. in our former studies, the relationship between host and guest in the anthropology of tourism usually referred to the re- lationship between local residents and tourists. However, as tourism development is often controlled by strong economic capital in china, the role of host has been replaced by other groups – for example, the per- formers employed by these external tourism enterprises. These performers belong to particular ethnic groups in their home areas, which constitute their ‘authenticity of life’. But after they arrive in Jiuzhaigou to work as performers, they encounter peo- ple outside their traditional culture, including tourists from all over the world, tour guides, their colleagues who come from other places and other ethnic groups, and the investors and managers from modern society. To meet their needs and for the benefit of others, they must play the role of Tibetan or Qiang people on stage. Thus, ‘staged authenticity’ is produced artificially.

From the perspective of cultural authenticity, the change process from ‘authenticity of life’ to ‘authenticity of performance’ reflects the reconstruc- tion of the cultural subject, represent- ed by the performers in Jiuzhaigou, and their ethnic identity, including an emerging place attachment to the tourist destination, as opposed to their hometown. The ‘authenticity of life’ to ‘authenticity of performance’ has originated not only from external pressures on the performers in Jiuzhai- gou, but also from internal factors, including inner identity, cohesion, and the need for daily survival. Accul- turation occurs; Foster (1969) argued that acculturation was the process of cultural change when two or more groups change after encountering each other. During the process of acculturation in Jiuzhaigou, the per- formers also reconstruct themselves and their identity, and re-shape their place of attachment.

From the perspective of cultural influence, these reconstructions are not only the outcome of accultura- tion, but also the reaction to cultural change, that is, the feedback from the ‘authenticity of performance’ to the ‘authenticity of life’. The influence of tourism on a host community is not only confined to the Front Stage area that tourists encounter directly, but also radiated and transferred farther afield by the cultural communicators. Through these forces of action and reaction, the performers realize their capacity for cultural adjustment and adaptation to new cultural surround- ings, with both positive and negative consequences. meanwhile, a new round of cultural authenticity has also been produced. on the basis of it, the new production of cultural authen- ticity helps the performers reshape their identity of place in a tourist destination. Thus, a new cultural authenticity has been produced in the context of tourism development, and the dynamic character of cultural authenticity in tourism development can be noted again.

Future research should be devoted to determining how positive cultur- al change and reaction can prevent negative results, in order that we can attempt to enhance the consciousness of ‘self ’ in traditional culture and improve the levels of self-esteem, self-identity and self-inheritance for minority ethnic groups.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Professor Victor King and Professor Yang Zhen- zhi for help with this paper.

REFERENCES

Baudrillard J. (1997). The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Cohen E. (1988). ‘Authenticity and commoditization in tourism’. Annals of Tourism Research, 15(3), 371-386. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(88)90028-X

Foster, G. (1969). Applied Anthropology. Boston: Little, Brown and company.

Goffman E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Garden city: Doubleday.

Maccannell D. (1973). ‘Staged authenticity: Arrangement of social space in tourist settings’. Ameri- can Journal of Sociology, 79(3), 589-603.

Suosheng W., and Joseph S. chen. (2015). ‘The influence of place identity on perceived tourism im- pacts’. Annals of Tourism Research, 52(3), 16-28. doi 10.1016/j.annals.2015.02.016

Smith V.L. (Ed.). (1989). Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism. Philadelphia: university of Pennsylvania Press, second revised edition.

Zhenzhi Y. (2006) ‘Front, curtain, Background: the exploration on the new mode of the protection of ethnic culture and tourism development’. Ethnic Studies, (2), 39-46

.