GC/MS Based Metabolite Profiling and Biological Activity of Leaves and Flower Heads of Tanacetum Cinerariifolium (Trevir.) Sch.Bip.

Milena Nikolova *, Vladimir Ilinkin, Elina Yankova-Tsvetkova, Marina Stanilova and Strahil BerkovPublished Date : 2022-07-11

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/CMUJNS.2022.038

Journal Issues : Number 3, July-September 2022

Abstract Flower heads and leaves of Tanacetum cinerariifolium (Trevir.) Sch. Bip. were examined separately for bioactive compounds and biological activity. The compounds were identified by GC/MS analysis. Studied extracts were evaluated for free radical scavenging activity, and for inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and seed germination. Free phenolic acids and flavonoid aglycones were found in larger quantities in the leaves than in the flower heads, where sterols, fatty acids, pyrethrins, sugars, sugar derivatives and bound phenolic acids predominated. Significant antiradical activity (IC50 /mL) and low acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity (IC50 >1 mg/mL) was found. Moderate inhibitory activity against germination and root elongation of Lolium perenne L. seeds was determined. The study presents for the first time detailed data on the content of phenolic acids in free, esterified and insoluble-bound forms in this species. Some of the identified flavonoids from the leaf extract are reported for the first time in the species.

Keywords: GC/MS, Flavonoids, Phenolic acids, Asteraceae (Composite)

Funding: This research was supported by the Bulgarian National Science Fund, Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science (Grant DN 16/2, 11.12.2017).

Citation: Nikolova, M., Ilinkin, V., Yankova-Tsvetkova, E., Stanilova, M. and Berkov, S. 2022. GC/MS based metabolite profiling and biological activity of leaves and flower heads of Tanacetum cinerariifolium (Trevir.) Sch.Bip.. CMU J. Nat. Sci. 21(3): e2022038.

INTRODUCTION

Tanacetum cinerariifolium (Trevir.) Sch. Bip. (dalmatian pyrethrum) syn.: Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium (Trevis.) Vis., Pyrethrum cinerariifolium Trevis. is herbaceous perennial herb, belonging to the Asteraceae (Composite) family. The plant forms rosette of many complex 5-6 lobed deeply incised fluffy leaves covered with hairs. The capitula consist of a large number of yellow tubular florets surrounded on their periphery by a row of ray linguals florets with long white petals. T. cinerariifolium is well known for its insecticidal properties [Grdiša et al., 2009], which are determined by the pyrethrins contained in all organs of the plant, particularly in the flower heads which contain more than 90% of the total pyrethrin content of the plant [Jovetic et al., 1994]. The species occurs naturally in a limited area along the east Adriatic coast [Nikolić et al., 2007; Grdiša et al., 2014], but it is cultivated as an agricultural crop in different countries around the world as Australia [Fulton, 1998], Uganda [Greenhill, 2007], France, Chile [Grdiša et al., 2009], Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda and Ecuador [Casida, 1980] Austria, Colombia, Cyprus, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Jawa, Korea, Nepal, Pakistan, Peru, Spain, Sri Lanka, Switzerland, Ukraine, Vietnam, West Himalaya and other https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:252275-1. Research on the content of secondary metabolites by the species has mainly been focused on studies related to Pyrethrin-I, Cinerin-I, Jasmolin-I, Pyrethrin-II, Cinerin-II, Jasmolin-II and their variation in naturally occurring populations or agricultural crops [Grdiša et al., 2009; Fulton, 1998; Kiriamiti et al, 2003; Grdiša et al., 2013]. Although less, there are reports on the content of other bioactive compounds in the species such as sesquiterpene lactones, triglycerides, fatty acids, terpenoids, carotenoids, chrysanthin, inulin [Maciver, 1995; Pîrvu et al., 2008; Ramirez et al., 2013]. The most studied and in detail biological activity of the species is insecticidal [Schoenig 1995; Crosby et al. 1995; Greenhill 2007; Cai et al., 2010] but a few studies reveal the presence of antiviral and antimicrobial activity for extracts of T. cinerariifolium [Marongiu et al., 2009]. Due to the lower content of pyrethrins in the leaves, they are not used in the extraction of natural pyrethrins and they have been insufficiently studied. The phytochemical profile of flower heads is also important because after the extraction of pyrethrins with a non-polar solvent, there are other more polar substances that would have the potential to find application for other areas. All the data presented so far determine the purpose of the study – comparative GC/MS based analysis of the metabolite profiles of extracts from flower heads and leaves of T. cinerariifolium. Also the extracts obtained were tested for free radical scavenging activity and for inhibition of seed germination and acetylcholinesterase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Flower heads and leaves of T. cinerariifolium plants were collected during the flowering stage from the ex situ collection of the Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research, Sofia, Bulgaria (Figure.1).

Extraction of plant material

Acetone exudates were prepared from air-dried, not ground (flower heads or leaves, per 1 g) by rinsing with acetone for 5 min to dissolve the lipophilic compounds accumulated on the surfaces. Methanolic extracts (5 g) were prepared from air-dried, ground flower heads or leaves, by classical maceration with methanol for 24 h.

Figure 1. Tanacetum cinerariifolium in ex situ collection of the Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research, Sofia, Bulgaria (photo: Marina Stanilova).

GC/MS analysis

Extraction procedure for GC–MS analysis: A sample of 100 mg of dried plant material as well as internal standards of 50 µL (1 mg/mL) of nonadecanoic acid, ribitol and 3,4 dichloro-4-hidroxy benzoic acid were placed in 2 mL Eppendorf tubes and extracted with 1 mL of MeOH for 24 h at room temperature. Subsequent extract processing was described by Nikolova et al. [2019]. Residue plant material after methanol extraction was hydrolyzed by 2 M NaOH, 4 h, at room temperature.

After acidification to pH 1-2 with conc. HCl, the phenolic compounds were extracted with EtOAc which was dried with anhydrous Na2SO4 and evaporated to obtain methanol insoluble-bound phenolic acids. Phenolic acids of the species were characterized in their three forms: free (identified in methanolic extract), esterified (identified in methanolic extract after alkaline hydrolysis) and methanol insoluble-bound (identified after alkaline hydrolysis in residue material after methanol extraction). Before GC/MS analysis studied, extracts and fractions were dissolved in 50 μL of pyridine and 50 μL of derivatization reagent N,O-bis-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) was added. The samples were heated at 70⁰C for 2 h. After the cooling, the samples were diluted with 300 μL of chloroform and that prepared were analyzed. The GC–MS spectra were recorded on a Termo Scientific Focus GC coupled with Termo Scientific DSQ mass detector operating in EI mode at 70 eV. The conditions of the analysis were presented by Berkov et al. [2021]. The measured mass spectra were deconvoluted using AMDIS 2.64 software before comparison with the databases. Retention Indices (RI) of the compounds were measured with a standard n-alkane hydrocarbons calibration mixture (C9–C36) (Restek, Cat No. 31614, supplied by Teknokroma, Spain).

The compounds were identified by comparing their mass spectra and retention indices (RI) with those of authentic standards and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) spectra library. The response ratios were calculated for each metabolite relative to the internal standard using the calculated areas for both components.

Free radical scavenging activity

The effect of methanolic extracts on DPPH radicals was estimated according to Stanojević et al. [2009]. The results were calculated by Software Prizm 3.00. All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Inhibitory activity on seed germination

A hundred seeds of Lolium perenne were placed in Petri dishes on filter papers moistened with the tested solutions. Methanolic extracts were applied as aqueous solutions at concentration of 1, 2 and 3 mg/mL. Seeds placed in Petri dishes on filter paper moistened with tap water were used as a control. The samples thus prepared were incubated at room temperature for 7 days. At the end of the week the rate of germination inhibition [%] was calculated by Atak et al. [2016]. The reduction in root growth caused by the extracts was estimated as a percentage of the length of the control roots using a formula after cited above source.

Acetylcholinesterase (AchE) inhibition assay

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of the methanolic extracts of the species was determined using Ellman's colorimetric method as modified by Lopez et al. [2009]. Extracts from the studied plant parts with concentrations of 0.001, 0.01, 0.01, 0.1 and 1 mg/mL were tested. Galanthamine was used as a positive control.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel software. The results are presented as mean with standard deviation (SD). The AChE inhibitory and free radical scavenging data were analyzed except Microsoft Excel and the software package Prism 9 (Graph Pad Inc., San Diego, USA). The IC50 values were measured in triplicate and the results are presented as means.

RESULTS

Acetone exudates and methanolic extracts of the leaves and the flower heads of T. cinerarifolim were separately analyzed by GC/MS. The results are presented at Table 1.

|

Table 1. Compounds identified in methanolic extracts and acetone exudates from leaves and flower heads of Tanacetum cinerariifolim. The values represent peak area ratios of each metabolite relative to the internal standard.

|

|||||||

|

|

Compounds

|

RT

|

RI

|

Methanolic extracts |

Acetone exudates |

||

|

Flower heads |

Leaves |

Flower heads |

Leaves |

||||

|

Pyrethrins |

Cinerin I (1) |

17.77 |

2210 |

53.7 |

|

|

|

|

Jasmolin I (2) |

19.03 |

2287 |

41.2 |

5.5 |

|

|

|

|

Pyrethrin I (3) |

19.18 |

2296 |

100.7 |

24.9 |

|

|

|

|

Cinerin II (4) |

23.32 |

2560 |

23.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

Jasmolin II (5) |

24.46 |

2636 |

16.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

Pyrethrin II (6) |

24.60 |

2646 |

26.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

Fatty acids |

Octanoic acid (7) |

8.10 |

1581 |

10.7 |

|

|

|

|

Hexadecanoic acid C16:0 (Palmitic acid) (8) |

13.04 |

1925 |

1077.9 |

686.5 |

74.3 |

42.3 |

|

|

Octadecadienoic acid C18:2 (Linoleic acid) (9) |

15.83 |

2090 |

698.1 |

386.8 |

|

|

|

|

Octadecenoic acid C18:1 (Oleic acid) (Е) (10) |

15.91 |

2102 |

12.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Octadecatrienoic acid C18:3 (Linolenic acid) (11) |

15.98 |

2120 |

73.9 |

498.1 |

|

|

|

|

Octadecanoic acid C18:0 (Stearic acid) (12) |

16.37 |

2132 |

246.9 |

296.1 |

|

|

|

|

Octadecanoic acid 3-hydroxy (13) |

19.39 |

2309 |

20.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

Eicosanoic acid C20:0 (Arachidic acid) (14) |

25.83 |

2342 |

12.8 |

19.5 |

|

|

|

|

Tricosanoic acid 2-methyl ether(15) |

26.82 |

2710 |

18.2 |

4.3 |

|

|

|

|

Tetracosanoic acid C24:0 (Lignoceric acid) (16) |

26.89 |

2740 |

12.3 |

26.0 |

|

|

|

|

2-Hydroxytetracosanoic acid (17) |

28.17 |

2801 |

18.2 |

2.0 |

|

|

|

|

2-Hydroxypentacosanoic acid (18) |

29.49 |

2914 |

8.7 |

1.3 |

|

|

|

|

Fatty alcohols |

Dodecanol (19) |

7.89 |

1560 |

2648.9 |

169.5 |

|

|

|

Tetradecanol (20) |

10.46 |

1759 |

25.8 |

8.6 |

|

|

|

|

Octadec-9Z-enol (21) |

16.31 |

2124 |

29.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

Octadecanol (22) |

16.74 |

2154 |

47.3 |

|

12.2 |

|

|

|

Tetracosanol (23) |

25.94 |

2740 |

72.5 |

|

108.3 |

36.5 |

|

|

Hexacosanol (24) |

28.66 |

2935 |

17.5 |

|

|

9.8 |

|

|

Sterols and Triterpenes |

Campesterol (25) |

32.68 |

3239 |

161.8 |

17.7 |

7.7 |

|

|

Stigmasterol (26) |

33.04 |

3319 |

199.0 |

67.9 |

|

|

|

|

β-Sitosterol (27) |

34.02 |

3386 |

972.7 |

312.6 |

90.0 |

|

|

|

β-Amyrin (28) |

34.34 |

3415 |

441.4 |

24.4 |

63.2 |

25.9 |

|

|

Oleanolic acid (29) |

35.16 |

|

|

|

|

78.5 |

|

|

Flavonoids |

Scutellarein 6-methyl ether (30) |

32.13 |

3189 |

|

|

|

9.5 |

|

Quercetagetin 3,6,3'-trimethyl ether (31) |

33.36 |

3292 |

|

|

0.6 |

196.5 |

|

|

Quercetagetin 3,6-dimethyl ether (32) |

33.63 |

3351 |

|

|

|

4.9 |

|

|

6-Hydroxyluteolin 6-methyl ether (33) |

34.21 |

3414 |

|

|

|

31.3 |

|

|

Organic acids |

Succinic acid (34) |

5.47 |

1310 |

295.0 |

9.8 |

6.4 |

37.2 |

|

Glyceric acid (35) |

5.54 |

1340 |

198.3 |

|

|

53.8 |

|

|

Fumaric acid (36) |

5.82 |

1347 |

84.6 |

|

1.7 |

13.6 |

|

|

Malic acid (37) |

6.96 |

1488 |

440.1 |

|

49.4 |

69.1 |

|

|

Pyroglutamic acid(38) |

7.47 |

1512 |

331.1 |

|

5.7 |

|

|

|

Threonic acid (40) |

7.52 |

1545 |

106.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Shcimic acid (39) |

11.03 |

1798 |

|

|

|

142.7 |

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Table 1. Continued. |

|||||||

|

Compounds

|

RT

|

RI

|

Methanolic extracts |

Acetone exudates |

|||

|

Flower heads |

Leaves |

Flower heads |

Leaves |

||||

|

Sugar and sugar derivatives |

meso-Erythritol (41) |

7.15 |

1711 |

38.7 |

4.7 |

|

|

|

Fructose 1(42) |

11.14 |

1800 |

242.9 |

135.0 |

|

|

|

|

Fructose 2 (43) |

11.21 |

1837 |

1124.7 |

256.9 |

51.3 |

29.6 |

|

|

Glucose (44) |

12.40 |

1882 |

114.9 |

|

|

|

|

|

Galactose (45) |

13.02 |

1920 |

191.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

myo-Inositol (46) |

13.43 |

2090 |

5504.4 |

195.3 |

|

|

|

|

Sucrose (47) |

24.41 |

2628 |

3911.5 |

441.2 |

396.4 |

1828.9 |

|

|

Free phenolic acids |

Salicylic acid (48) |

7.31 |

1512 |

42.8 |

58.9 |

|

|

|

4(p)-Hydroxybenzoic acid (49) |

8.74 |

1635 |

|

16.1 |

2.6 |

|

|

|

Vanilic acids (50) |

10.52 |

1776 |

|

|

6.5 |

18.4 |

|

|

Protocatechuic acid (51) |

11.24 |

1813 |

|

48.7 |

39.7 |

147.1 |

|

|

Quinic acid (52) |

11.85 |

1843 |

3033.6 |

5320.5 |

21.4 |

2613.9 |

|

|

Caffeic acid trans(53) |

16.44 |

2141 |

|

157.3 |

|

|

|

|

Chlorgenic acid (54) |

30.90 |

3100 |

714.7 |

3271.2 |

|

250.0 |

|

|

Methanol extractable hydrolysable phenolic acids |

Salicylic acid (55) |

7.31 |

1512 |

5.9 |

2.4 |

|

|

|

3,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid (56) |

9.88 |

1720 |

6.2 |

4.1 |

|

|

|

|

Vanilic acid (57) |

10.52 |

1776 |

9.7 |

18.2 |

|

|

|

|

Protocatechuic acid (58) |

11.24 |

1813 |

44.6 |

39.3 |

|

|

|

|

Quinic acid (59) |

11.85 |

1843 |

25.4 |

58.4 |

|

|

|

|

4(p)- Hydroxycinnamic acid trans (60) |

13.27 |

1948 |

9.4 |

12.7 |

|

|

|

|

3,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid (61) |

14.40 |

2008 |

60.9 |

|

|

|

|

|

Caffeic acid (62) |

16.44 |

2141 |

385.1 |

288.8 |

|

|

|

|

Methanol insoluble hydrolysable bound phenolic acids |

4(p)-Hydroxybenzoic acid (63) |

8.74 |

1635 |

18.1 |

6.6 |

|

|

|

Vanilic acid (64) |

10.52 |

1776 |

33.6 |

2.7 |

|

|

|

|

Protocatechuic acid (65) |

11.24 |

1813 |

210.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

Quinic acid (66) |

11.85 |

1843 |

103.3 |

14.0 |

|

|

|

|

4(p)- Hydroxycinnamic acid (67) |

13.27 |

1948 |

22.4 |

5.9 |

|

|

|

|

Caffeic acid cis (68) |

13.78 |

1984 |

286.8 |

|

|

|

|

|

3,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid (69) |

14.40 |

2008 |

3.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

Ferulic acid trans (70) |

15.76 |

2100 |

12.9 |

|

|

|

|

|

Caffeic acid trans (71) |

16.44 |

2141 |

3557.2 |

794.9 |

|

|

|

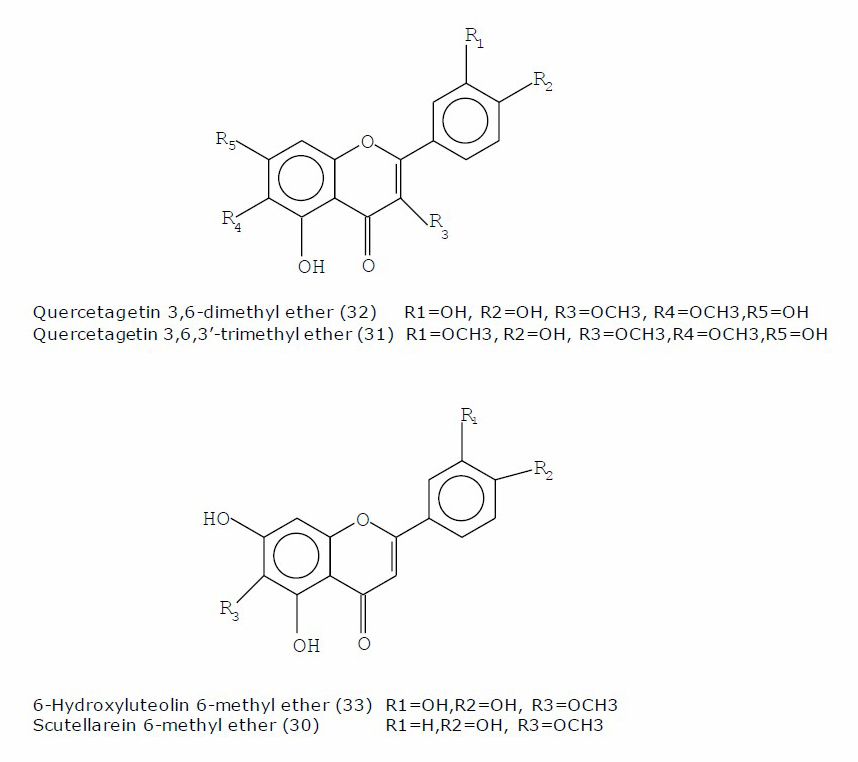

Figure 2. Structures of the identified flavonoid aglycones.

Metabolite profiles of acetone exudates

Flavonoid aglycones (30-33), sterols (25,27), fatty acids (8) and alcohols (22-24), organic acids (34-39), free phenolic acids (49-52,54) were found in the acetone exudates. Methyl derivatives of quercetin, apigenin and luteolin, substituted at 6-position were identified as surface flavonoids. Quercetagein 3,6,3-trimethyl ether (jaceidin, 31) was found as the main flavonoid of both exudates, moreover, it is the only flavonoid identified in the exudate from the flower heads. The rest flavonoid aglycones: scutellarein 6-methyl ether (30), 6-hydroxyluteolin 6-methyl ether (nepetin, 33) and quercetagetin 3,6-dimethyl ether (axillarin, 32) were identified in the exudate of the leaves. The structures of the identified flavonoid aglycones were presented at Figure 2. Campesterol (25), stigmasterol (26) and ß-amayrin (28) were determined as major components in flower heads exudate. Free phenolic acids – chlorogenic (54), quinic (52) and protocatechuic (51) – were found to be major in leaf exudate.

Metabolite profiles of metanolic extracts

Pyrethrins (1-6), phenolic (48-71), fatty (7-18) and organic (34-40) acids, sterols (25-27), sugar alcohols (41,46) were identified in the methanolic extracts of flower heads and leaves by GC/MS. The comparative analysis showed that fatty acids and alcohols were mainly concentrated in the flowers and less in the leaves. Palmitic (8), stearic (12) and linoleic (9) acids were established as dominant. Sterols (25-27) and β-amyrin (28) were also proven in flower and leaf extracts, but in flower heads they were in much larger amounts. Saccharides and sugar alcohol (46) were established again in higher quantities in the flower heads extract. Phenolic acids were determined in their free (48,49,51-54), esterified (55-62) and methanol insoluble bound forms (63-71). Free phenolic acids were concentrated mainly in the leaves; chlorogenic acid was determined as major. Alkaline hydrolysable esterified (55-62) and especially bound phenolic acids (63-71) were found in greater amounts in the flower heads extracts than in the leaf extracts. Caffeic acid (71) was determined as the predominant bound phenolic acid. Moreover, this acid was found in high levels in free (53), esterified (62) and methanol insoluble (68,71) forms in both plant organs. Most phenolic acids were found in bound form.

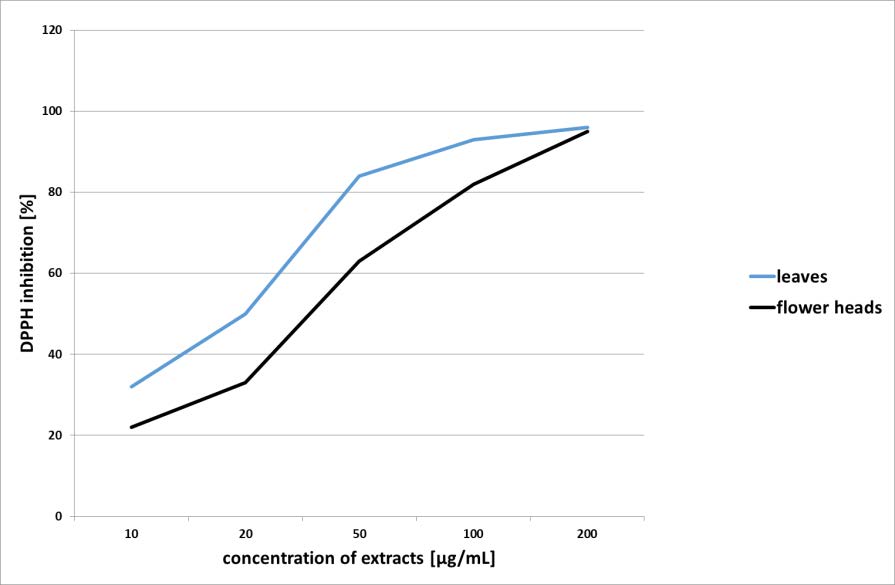

Free radical scavenging activity

Methanolic extracts from leaves and flower heads of T. cinerariifolium were evaluated for antiradical activity by DPPH assay. The studied extracts revealed significant activity with IC50=24,49 µg/mL and IC50=45,34 µg/mL for the extracts from the leaves and the flower heads, respectively (Figure 3). However, the leaf extract showed higher activity, due to the higher content of phenolic acids, especially chlorogenic acid (54).

Figure 3. Free radical scavenging activity of studied T. cinerariifolium extracts against DPPH radicals.

Inhibitory activity on seed germination

The inhibitory effect of the studied methanolic extracts on the germination of Lolium perenne seeds was assessed (Table 2).

Table 2. Inhibition on seed germination and seed root growth in Lolium perenne under the influence of the studied T. cinerariifolium extracts.

|

Concentraction (mg/mL)

|

Inhibition of germination (%) |

Inhibition of root growth (%) |

||

|

Extract of leaves

|

Extract of flower heads |

Extract of leaves |

Extract of flower heads |

|

|

1 |

5 ± 3 |

7 ± 4 |

17 ± 5 |

15 ± 4 |

|

2 |

16 ± 5 |

19 ± 8 |

45 ± 8 |

30 ± 6 |

|

3 |

30 ± 9 |

42 ± 10 |

66 ± 10 |

58 ± 9 |

The results showed that the tested extracts exhibited moderate activity in the studied concentration range 1-3 mg/mL. No difference was found in the activity of the extracts from the leaves and from the flower heads. However, more significant inhibition of root growth was established. The percentage of growth inhibition of L. perenne roots was around 50% at the highest concentration tested.

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity

The ability of the studied extracts to inhibit acetylcholinesterase was evaluated. In the tested concentration range 0.1-1000 µg/mL a low inhibitory effect (IC50 >1mg/mL) was observed for both extracts.

DISCUSSION

Metabolite profiles

Phytochemical profiles of acetone exudates and methanolic extracts from the leaves and flower heads of T. cinerariifolium were determined. Acetone exudates have been widely used in the study of externally located flavonoid aglycones, known also as exudate, surface, and externally flavonoids [Wollenweber and Dietz, 1981; Onyilagha and Grotewold, 2004]. Derivatives of quercetin, apigenin and luteolin 6-O-substituted were identified in the leaf exudate. Flavonoid aglycone – quercetagein 3,6,3'-trimethyl ether (31) has been previously reported as component of flower heads of T. cinerariifolium [Sashida et al., 1983; Kumar et al., 2005]. To the best of our knowledge, flavonoid aglycones: scutellarein 6-methyl ether (30), 6-hydroxyluteolin 6-methyl ether (33) and quercetagetin 3,6-dimethyl ether (32) are reported for the first time here as a component of T. cinerariifolium leaves. These flavonoid aglycones have been reported for other Tanacetum species such as Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Schultz Bip. [Williams et al., 1999; Long et al., 2003; Végh et al., 2018]. Variety of fatty acids as well as sterols was found in the flower head extract, which is in accordance with the data reported by Kumar et al. [2005].

In the present study phenolic acids were identified in their free (48-54), esterified (55-62) and methanol insoluble bound (63-71) forms. Chlorogenic acid was found as major free phenolic acid in the leaves. Gecibesler et al. [2016] reported such a result for Tanacetum cilicicum (Boiss.)Grierson. The result obtained that bound phenolic acids predominate in the flower heads suggests that waste products after extraction of pyrethrins can be used for a source of phenolic acids.

Biological activity

T. cinerariifolium extracts from flower heads and leaves were evaluated for free radical scavenging, and for inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and seed germination. The antiradical activity of the tested extracts expressed by IC50 values is classified as very active according to the scale described by Reynertson, et al. [2005]. Concerning acetylcholinesterase activity the values obtained (IC50 > 1mg/mL) show low inhibition. Similar results have been reported for extracts and essential oils from other Tanacetum species [Polatoğlu et al., 2015a; Yur et al., 2017]. Moreover, strong AChE activity has been found for essential oils only when applied in pure form, if applied diluted (1-10 mg/mL) their activity is greatly reduced [Polatoğlu et al., 2015b]. Sashida et al. [1983] noted that extract from the flower heads of C. cinerariaefolium inhibited the growth of Chinese cabbage roots, but no more detailed information was found. Comparing the present results with data reported for other species [Wahyuni et al., 2017] the observed inhibition of seed germination can be determined as moderate. Although observed differences in the metabolic profiles of extracts from leaves and flower heads, significant differences in their biological activity was not established. Only the leaf extracts showed slightly higher antioxidant activity than those of the flower heads, which correlates with a higher phenolic acid content in them.

CONCLUSION

GC/MS-based analysis on the phytochemical profiles of Tanacetum cinerariifolium leaves and flower heads was conducted. Similar metabolic profiles were found in extracts from different organs, but the leaves had a higher content of free phenolic acids and flavonoid aglycones, while pyrethrins, sterols, fatty acids, sugars, bound phenolic acids were found in larger amounts in the flower heads. Considerable free radical scavenging activity, moderate inhibition on seed germination and low acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity were established for the studied extracts. Differences between extracts from leaves and flower heads concerning the studied activities were not found. The presented data show that the species is rich in bioactive compounds (especially phenolic acids) that can be isolated from waste plant material after pyrethrin extraction.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Bulgarian National Science Fund, Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science (Grant DN 16/2, 11.12.2017).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the work presented here, read and approved the final manuscript. MN conceived, designed the experiments, contributed to the GC/MS and antiradical analysis and wrote first version of the manuscript; ETs. carried out the seed germination experiment; VI and MS contributed to collection of the plant material; SB contributed to the AChE and GC/MS analysis and to the writing of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they hold no competing interests.

REFERENCES

Atak, M., Mavi, K., and Uremis, I. 2016. Bio-herbicidal effects of oregano and rosemary essential oils on germination and seedling growth of bread wheat cultivars and weeds. Romanian Biotechnological Letters. 21: 11149-11159.

Berkov, S., Pechlivanova, D., Denev, R., Nikolova, M., Georgieva, L., Sidjimova, B., Bakalov, D., Tafradjiiska, R., Stoynev, A., Momekov, G., and Bastida J. 2021. GC-MS analysis of Amaryllidaceae and Sceletium-type alkaloids in bioactive fractions from Narcissus cv. Hawera. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 35(14): e9116.

Cai, H.J., You, M.S., Fu, J.W., Ryall, K., and Li, S.Y. 2010. Lethal effects of pyrethrins on spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana). Journal of Forestry Research. 21: 350-354.

Casida, J.E. 1980. Pyrethrum flowers and pyrethroid insecticides. Environmental Health Perspectives. 34: 189-202.

Crosby, D.G. 1995. Environmental Fate of Pyrethrins. In J. E. Casida, and G. B. Quistad (Eds.). Pyrethrum Flowers: Production, Chemistry, Toxicology, and Uses (pp. 194-213). University Press, New York: Oxford.

Fulton, D. 1998. Agronomic and seed qualities in pyrethrum (Tanacetum cinerariaefolium (Trevir.) Sch. Bip.). PhD Thesis, School of Agricultural Sciences, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia.

Gecibesler, I.H., Kocak, A. and Demirtas, I. 2016). Biological activities, phenolic profiles and essential oil components of Tanacetum cilicicum (BOISS.) GRIERSON. Natural Product Research. 30: 2850-2855.

Grdiša, M., Carović-Stanko K., Kolak, I., and Šatović, Z. 2009. Morphological and biochemical diversity of Dalmatian pyrethrum (Tanacetum cinerariifolium (Trevir.) Sch. Bip.). Agriculturae Conspectus Scientificus. 74: 73-80. https://hrcak.srce.hr/39335

Grdiša, M., Babić, S., Periša, M., Carović-Stanko, K., Kolak, I., Liber, Z., Jug-Dujakovic, M., and Satovic, Z. 2013. Chemical Diversity of the Natural Populations of Dalmatian Pyrethrum (Tanacetum cinerariifolium (Trevir.)Sch.Bip.) in Croatia. Chemistry & Biodiversity. 10: 460–472.

Grdiša, M., Liber, Z., Radosavljević, I., Carović-Stanko, K., Kolak, I., and Satovic, Z. 2014. Genetic diversity and structure of Dalmatian pyrethrum (Tanacetum cinerariifolium Trevir./Sch./Bip., Asteraceae) within the Balkan refugium. PloS one. 9: e105265.

Greenhill, M. 2007. Pyrethrum production: Tasmanian–success story. Chronica Horticulturae. 47: 5-8.

Jovetic, S. 1994. Natural Pyrethrins and Biotechnological Alternatives. Biotechnology and Development Monitor. 21: 12-13.

Kiriamiti, H.K., Camy, S., Gourdon, C., and Condoret, J.S. 2003. Pyrethrin extraction from pyrethrum flowers using carbon dioxide. Journal of Supercritical Fluids. 26: 193-200.

Kumar, A., Singh, S., and Bhakuni, R. 2005. Secondary metabolites of Chrysanthemum genus and their biological activities. Current Science. 89: 1489-1501. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24110912

Long, C., Sauleau, P., David, B., Lavaud, C., Cassabois, V., Ausseil, F., and Massiot, G. 2003. Bioactive flavonoids of Tanacetum parthenium revisited. Phytochemistry. 64: 567-569.

López, S., Bastida, J., Viladomat, F., and Codina, C. 2002. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of some Amaryllidaceae alkaloids and Narcissus extracts. Life Science. 71: 2521–2529.

Maciver, D.R. 1995. Constituents of pyrethrum extract. In J.E. Casida, and G.B. Quistad (Eds.). Pyrethrum Flowers: Production, Chemistry, Toxicology, and Uses (pp. 108-122). University Press, New York: Oxford.

Marongiu, B., Piras, A., Porcedda, S., Tuveri, E., Laconi, S., Deidda, D., and Maxia, A. 2009. Chemical and biological comparisons on supercritical extracts of Tanacetum cinerariifolium (Trevir) Sch. Bip. with three related species of chrysanthemums of Sardinia (Italy). Natural Product Research. 23: 190-199.

Nikolić, T., and Rešetnik, I. 2007. Plant uses in Croatia. Phytologia Balcanica. 13: 229-238.

Nikolova, M., Aneva, I., Zhelev, P., and Berkov, S. 2019. GC-MS based metabolite profiling and antioxidant activity of Balkan and Bulgarian endemic plants. Agriculturae Conspectus Scientificus. 84: 59-65. https://hrcak.srce.hr/218536

Onyilagha, J., and Grotewold, E. 2004. The biology and structural distribution of surface flavonoids. In Pandalai, S.G. (Ed.). Recent research developments in plant science Research Signpost: Trivandrum; India, 2, pp. 53-71.

Pîrvu, L., Armatu, A., and Coprean, D. 2008. Contributions to the chemical characterization of some vegetal products with insecticidal activity obtained from Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium L. acclimatized in Constanta. In 4th International Symposium “New research in biotechnology” USAMV (pp. 426-436). Bucharest, Romania.

Polatoğlu, K., Karakoç, Ö.C., Yücel, Y. Y., Demirci, B., Gören, N., and Başer, K.H.C. 2015a. Composition, insecticidal activity and other biological activities of Tanacetum abrotanifolium Druce. essential oil. Industrial Crops and Products. 71: 7-14.

Polatoğlu, K., Servi, H., Yücel, Y., and Nalbantsoy, A. 2015b. Cytotoxicity and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory and PRAP activities of the essential oils of selected Tanacetum L. species. Natural Volatiles & Essential Oils. 2: 11-16.

Ramirez, A.M., Saillard, N., Yang, T., Franssen, M.C.R., Bouwmeester, H.J., and Jongsma, M.A. 2013. Biosynthesis of Sesquiterpene Lactones in Pyrethrum (Tanacetum cinerariifolium). Plos one. 8: e65030.

Reynertson, K., Basile, M., and Kennelly, E. 2005. Antioxidant Potential of Seven Myrtaceous Fruits. Ethnobotany Research & Applications. 3: 025-036. http://ethnobotanyjournal.org/index.php/era/article/view/49

Sashida, Y., Nakata, H., Shimomura, H., and Kagaya, M. 1983. Sesquiterpene lactones from pyrethrum flowers. Phytochemistry. 22: 1219–1222.

Schoenig, G.P. 1995. Mammalian toxicology of pyrethrum extract In J. E. Casida, and G. B. Quistad (Eds.). Pyrethrum Flowers: Production, Chemistry, Toxicology, and Uses (pp. 249-257). University Press, New York: Oxford.

Stanojević, L., Stanković, M., Nikolić V., Nikolić, L., Ristić, D., Čanadanovic-Brunet, J., and Tumbas, V. 2009. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic and flavonoid contents of Hieracium pilosella L. extracts. Sensors. 9: 5702–5714.

Végh, K., Riethmüller, E., Hosszú, L., Darcsi, A., Müller, J., Alberti, Á., Tóth, A., Béni, S., Könczöl, Á., Balogh, G.T., and Kéry, Á. 2018. Three newly identified lipophilic flavonoids in Tanacetum parthenium supercritical fluid extract penetrating the Blood-Brain Barrier. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 149: 488-493.

Yur, S., Tekin, M., Göger, F., Başer, K., Özek, T., and Özek, G. 2017. Composition and potential of Tanacetum haussknechtii Bornm. Grierson as antioxidant and inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase, tyrosinase, and α-amylase enzymes. International Journal of Food Properties. 20: S2359–S2378.

Wahyuni, D., van der Kooy, F., Klinkhamer, P., Verpoorte, R., and Leiss, K. 2013. The Use of Bio-Guided Fractionation to Explore the Use of Leftover Biomass in Dutch Flower Bulb Production as Allelochemicals against Weeds. Molecules, 18: 4510–4525.

Williams, C.A., Harborne, J.B., Geiger, H., and Hoult, J.R.S. 1999. The flavonoids of Tanacetum parthenium and T. vulgare and their anti-inflammatory properties. Phytochemistry. 52: 1181–1182.

Wollenweber, E. and Dietz, V. H. 1981. Occurrence and distribution of free flavonoid aglycones in plants. Phytochemistry 20: 869-932.

OPEN access freely available online

Chiang Mai University Journal of Natural Sciences [ISSN 16851994]

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Milena Nikolova *, Vladimir Ilinkin, Elina Yankova-Tsvetkova, Marina Stanilova and Strahil Berkov

Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, Bulgaria

Corresponding author: Milena Nikolova, E-mail: mtihomirova@gmail.com

Total Article Views

Editor: Korakot Nganvongpanit,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: January 10, 2022;

Revised: March 16, 2022;

Accepted: March 17, 2022;

Published online: March 24, 2022