Serological Status of Hepatitis B Virus Infection Among Hill-Tribe Children in Northern Thailand, in 2018

Yada Aronthippaitoon, Nipatsorn Boonserm, Tunyalak Saming, Sucheewa Udomsilp, Sirinath Choyrum, Sayamon Hongjaisee, Jintana Yanola, Nicole Ngo-Giang-Huong, Sakorn Pornprasert, and Woottichai Khamduang*Published Date : 2022-07-11

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/CMUJNS.2022.037

Journal Issues : Number 3, July-September 2022

Abstract Thailand has integrated Hepatitis B (HB) vaccine for newborns into the national Expanded Program on Immunization since 1992. The HB vaccination coverage was reported >96% in 2019 but the coverage among inhabitants of remote rural areas, particularly among hill-tribe children, remains unclear. This cross-sectional study aims to investigate the hepatitis B virus (HBV) seroprevalence among hill-tribe children living in 3 different areas in Omkoi District, Chiang Mai province, Thailand during September-November, 2018. Plasma samples were first tested for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). Sample negative for HBsAg were then tested for antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs) levels and antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc). A total of 419 hill-tribe children were recruited, their median age was 11 years (interquartile range 9-12 years). Eighteen children (4.3%, 95%CI 2.6-6.7) were HBsAg positive. Among 401 remaining children, 269 had no HBV markers (67.1%, 95%CI 62.3-71.7), 91 (22.7%, 95%CI 18.7-27.1) were positive for anti-HBs only, 23 (5.7%, 95%CI 3.7-8.5) were positive for anti-HBc and anti-HBs, and 18 (4.5%, 95%CI 2.7-7.0) positive for anti-HBc only. The high prevalence of children susceptible to HBV infection and the high proportion of HBV infected children indicate that vaccination strategy needs to be improved in this rural area. Moreover, HBV serologic investigations are necessary in other rural areas to improve HB vaccination coverage.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus; Prevalence; Vaccination; Serological markers; Children; Thailand

Funding: This work was supported by the research fund from the Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University.

Citation: Aronthippaitoon, Y., Boonserm, N., Saming, T., Udomsilp, S., Choyrum, S.,Hongjaisee, S., Yanola, J., Ngo-Giang-Huong, N., Pornprasert, S., and Khamduang, W. 2022. Serological status of hepatitis B virus infection among hill-tribe children in northern Thailand, in 2018. CMU J. Nat. Sci. 21(3): e2022037.

INTRODUCTION

Infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the most common cause of viral hepatitis worldwide (World Health Organization (WHO) 2021). Fortunately, hepatitis B (HB) vaccine had been available for decades and it is considered to be one of the most effective vaccines for preventing infectious diseases (Meireles, Marinho, and Van Damme 2015). However, mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HBV still occurs especially in Asia (Chongsrisawat et al. 2006).

In Thailand, HB vaccination has been integrated into the national Expanded Program for Immunization (EPI) for all newborns since 1992 (Poovorawan et al. 2000; Lolekha et al. 2002). The immunization schedule originally recommended at birth (monovalent formulation), 2, 4 and 6 months (polyvalent formulations). Administration of hepatitis B immunoglobulin and/or an extra dose of monovalent HB vaccine is now recommended exactly at one month of age in infants born to HBsAg positive mothers (Pediatric Infectious Disease Society of Thailand 2012). This policy has led to a dramatic decrease of HBV infection in the children population during the past several years (Lolekha et al. 2002). The coverage rate of newborn HB vaccination has been reported to be greater than 96% in 2019 (World Health Organizaton (WHO) 2019). Although this coverage rate is quite high, it may not reflect the coverage in rural and remote areas where the access to HB vaccination is more difficult (Jutavijittum et al. 2005; Khamduang et al. 2019) or HB vaccination may be more challenging. Beside the reason of the poor access to health care, the hill-tribes living in those areas are vulnerable and susceptible to HBV infection for several reasons, such as their own traditional culture and lifestyles (e.g., tattooing and piercing), low education, language barriers (Keereekamsuk et al. 2007; Lukas 2018). A study conducted among 210 hill-tribe children in 1 village in northern Thailand reported 12.4% anti-HBs antibodies rate, much lower than that reported nationwide in EPI's report. In addition, a high proportion of children susceptible to HBV infection still exists (Khamduang et al. 2019). In order to extend these results, we assessed the serologic markers for HBV infection and vaccination among hill-tribe children population in 3 different areas in Omkoi District, Chiang Mai, Thailand. Results of this study may contribute to improve HB vaccination implementation in remote and rural areas.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

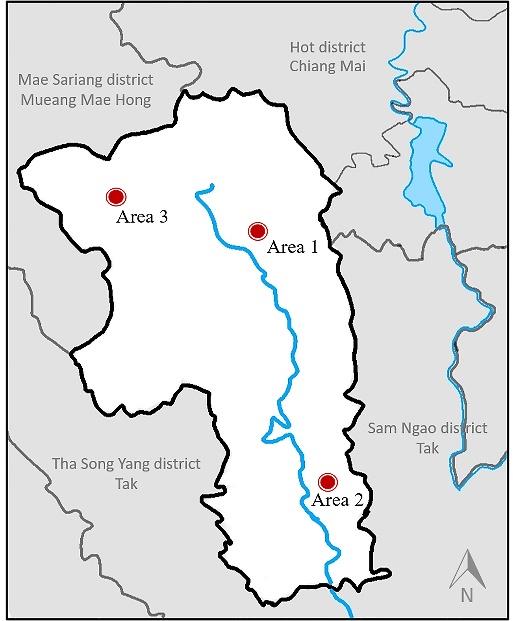

This study was designed as a cross-sectional study to investigate the HBV seroprevalence among hill-tribe children living in Omkoi District, Chiang Mai province, located in the north of Thailand, during September-November, 2018. We collected plasma samples in 3 villages in rural areas (Figure 1). All children registered in a kinder garden, primary, and secondary schools with age ranging from 6-15 years old. This study was conducted with the approval from the ethical committee of Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University (Approval number: AMSEC-64EM-027). This project used residual archived samples from a previous study investigating anemia in hill tribe students (Yanola et al. 2018). All data were fully anonymized before accessed them and a self-defined patient code was used to classify samples so that it cannot be linked to a child.

Figure 1. Map of Omkoi district, Chiang Mai province, Thailand. The dots represent the areas where samples were collected.

Serological assays

Plasma samples were initially tested for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) using the MUREX HBsAg version 3 kit, DiaSorin (Italy) with a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 98% (manufacturer’s insert package). Negative-HBsAg samples were further quantified for the level of antibodies to hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs) using the ETI-AB-AUK-3 kit, DiaSorin (Italy) (99.1% sensitivity and 98.2% specificity). Children with an anti-HBs antibody level greater than 10 international units/liter (IU/L) were considered as having protective immunity. The negative-HBsAg samples were also tested for antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) using the MUREX anti-HBc total kit, DiaSorin (Italy) (100% sensitivity and 99.7% specificity).

Children with HBsAg-positive result were considered as HBV infected. If HBsAg tests were negative, children were categorized into 4 groups according to their anti-HBs and anti-HBc antibodies status: 1) anti-HBc and anti-HBs positive indicated immunity due to natural HBV infection, 2) only anti-HBc positive indicated HBV exposure (resolved infection or chronic infection with low viral replication level), 3) only anti-HBs positive indicated immunity due to HB vaccination, and 4) negative for both anti-HBc and anti-HBs indicate susceptibility to HBV infection.

Statistical analysis

The characteristic data of hill-tribe children, including age at blood collection, gender, and registered education are expressed using numbers, percentage and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for categorical data and median with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous data. The comparison of median of anti-HBs level among HBsAg negative groups was calculated using Mann-Whitney U test. The STATA version 14.1 software (Statacorp, Texas, USA) was used for analyzing all data in statistical. Differences were considered statistically significant when the p-value was ≤ 0.05. Graphics were generated using Graphpad software 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

A total of 419 hill-tribe children were recruited, 252 (60.1%) were female. The median age was 11 years (interquartile range 9-12 years). Among all children, 262 (62.5%) registered in primary school, 126 (30.1%) in secondary school, 28 (6.7%) in kindergarten, and 3 (0.7%) had no data available.

Serological status of HBV infection

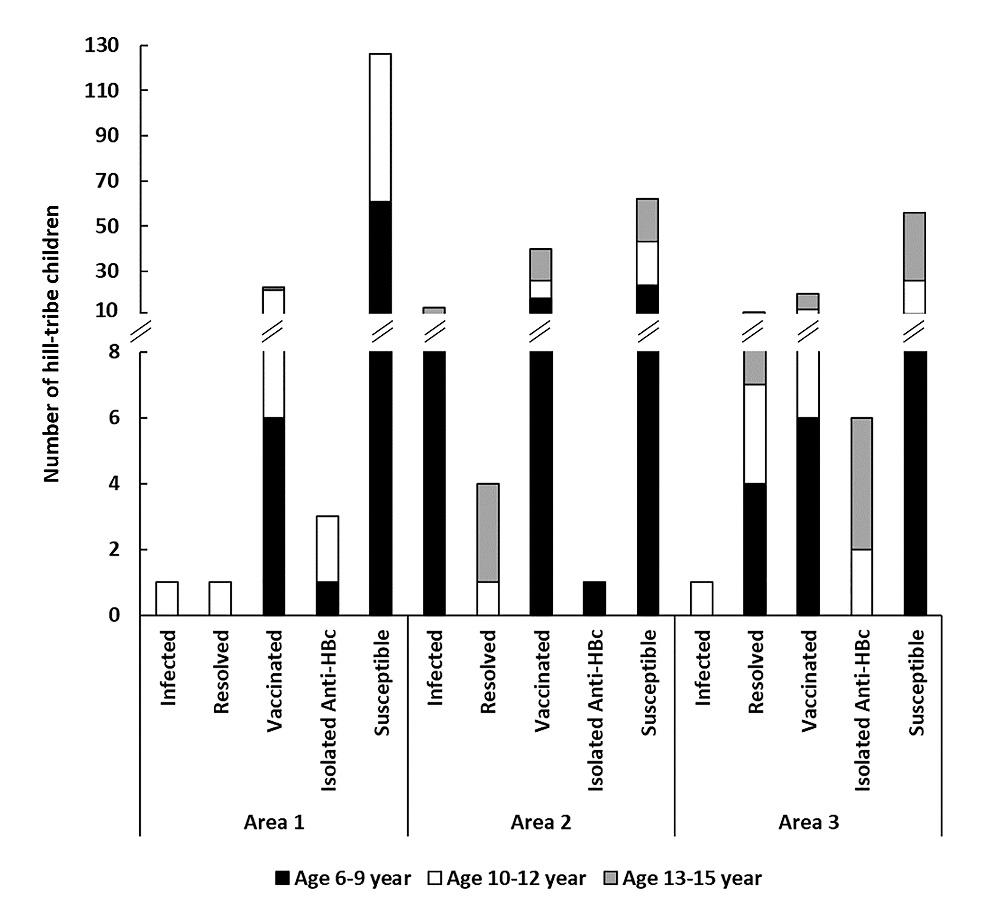

Of 419 children, 18 (4.3%, 95%CI 2.6-6.7) were positive for HBsAg; 14 were females and 4 were males. Over 70% (14 of 18) lived in area 2 (Figure 2). One child was HBsAg positive and had anti-HBs level of 21 mIU/ml.

The remaining of 401 HBsAg-negative children, 23 (5.7%, 95%CI 3.7-8.5) were positive for anti-HBc and anti-HBs, considered as having resolved HBV infection; 91 (22.7%, 95%CI 18.7-27.1) were positive only anti-HBs, considered as vaccinated; 18 (4.5%, 95%CI 2.7-7.0) were positive only anti-HBc, considered as having been previously exposed to HBV; and 269 (67.1%, 95%CI 62.3-71.7) showed negative for all serologic markers of HBV infection and were considered as susceptible to infection (Figure 2, Table S1)

Figure 2. HBV serological status of hill-tribe children according to their area and age group.

Anti-HBs levels according to HBV serological status

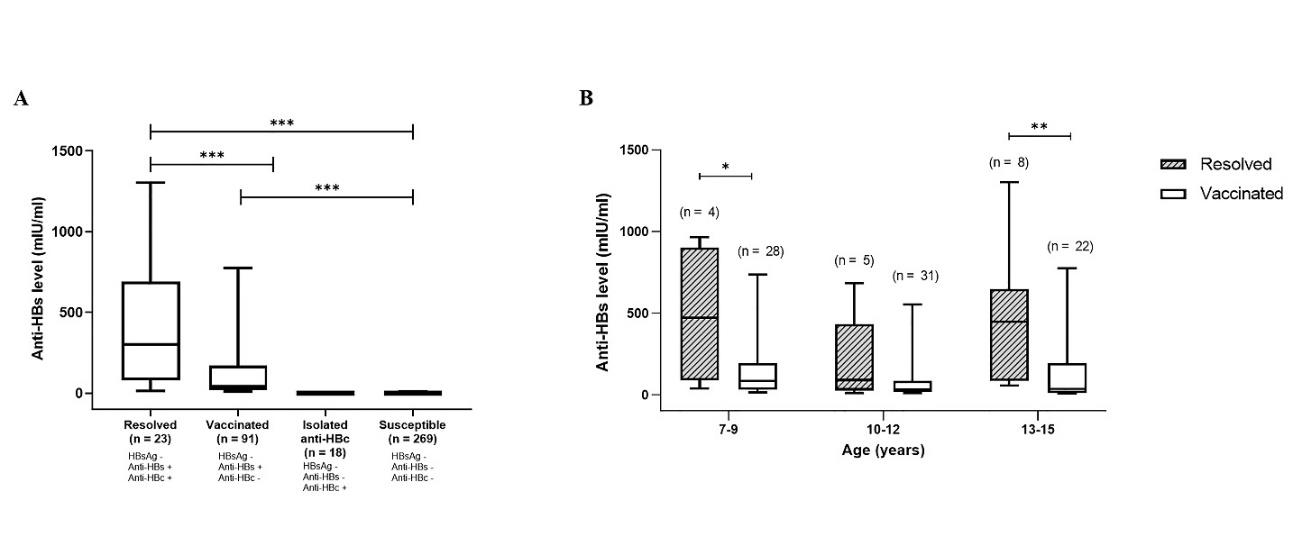

The median of anti-HBs levels among children who resolved from natural HBV infection (303 mIU/ml, IQR: 81-689) was significantly higher than that among vaccinated children (45 mIU/ml, IQR: 21-187, P-value <0.001, Figure 3A). This higher anti-HBs level among children with resolved HBV was observed over all age groups, as compared to vaccinated group (Figure 3B), except among the group of 10-12 years.

Figure 3. Anti-HBs antibody levels among hill-tribe children. (A) Anti-HBs antibody levels among hill-tribe children aged 6-15 years according to their HBV serological statuses. The graphs indicate the medians of anti-HBs levels with interquartile and ranges. (B) Levels of anti-HBs among children with resolved HBV infection versus HB vaccinated children according to their age. *, P-value <0.05, **, P-value <0.01, ***, P-value <0.001.

DISCUSSION

We found a relatively low prevalence of anti-HBs antibody (22.7%) among hill-tribe children living in 3 villages in rural areas of northern Thailand. In Thailand, the HB vaccine is generally administered free-of-charge to infants at birth and subsequently at 1, 2, 4, and 6 months of age if infants are born to HBsAg positive mothers or 2, 4, and 6 months if born to HBsAg negative mothers. The HB vaccination started at 1992 with a coverage rate of 15%, and estimated to be 96% in 2019 (World Health Organizaton (WHO) 2019). However, this coverage rate may vary between urban and rural areas. Urban school children have been reported to have higher rate of vaccination than children in remote areas in 2005 (89.1% vs 46.9%) (Jutavijittum et al. 2005). Our study shows a low rate of vaccine response (22.7%) although these children were born during a time when newborn-HB vaccination was integrated in the EPI. This low HB vaccine response rate is consistent with the rate observed in a previous study conducted in Omkoi District in 2014 (12.4%) (Khamduang et al. 2019). The low rate of vaccine-induced anti-HBs among hill-tribe children might be due to host response, incomplete vaccination, no persistent anti-HBs, or no HB vaccination. Several studies reported persistent anti-HBs antibodies decrease over time especially >10 years after primary vaccination at birth (Saso and Kampmann 2017; Verso et al. 2019). In addition, the difficulty to access to HB vaccination services may be related to factors such as low socioeconomic status, limited access to healthcare facilities, far distance to healthcare services, language barrier, lack of knowledge of pregnant women about the importance of antenatal care and a lack of concerns on HBV infection and prevention (Keereekamsuk et al. 2007; Apidechkul, Laingoen, and Suwannaporn 2016; Wang et al. 2017; Lukas 2018; Yang et al. 2018).

Regarding the rate of exposure to HBV, high proportion (14.1%) of natural acquired infection was identified among hill-tribe children, some were (4.3%) on-going HBV infection (children positive for HBsAg). These results are probably a consequence of low HB vaccination coverage in this population. A previous study conducting in Chiang Mai in 2005, reported 1.2% prevalence of HBsAg among children aged 4-9 years old; 0.8% among children living in remote area versus 1.7% in urban area (Jutavijittum et al. 2005). Another study reported 1.9% HBsAg rate among rural children in 2014 (Khamduang et al. 2019). Four years after that study, we still found 4.3% HBsAg positivity rate. Various factors have been reported associated with an increase in HBV infection risk in hill-tribe children, particularly mother-to-child transmission and community-based transmission during early childhood (Yeung and Roberts 2001). The HBsAg seroprevalence among married hill-tribe women in northern Thailand was reported at 8.2% (Pichainarong et al. 2003). Horizontal transmission is also another cause of childhood infections, such as close contact with HBV carriers with open wounds, sharing personal sharp items, nail biting, and scratching to HBV infected person (Hsu et al. 1993; McIntosh et al. 1997; Yeung and Roberts 2001). Although not statistically significant, we observed the seroevidence of HBV contacts was higher in children aged 13–15-year-old 20.5% as compare to younger children. This is likely related either to household contact with infected adults or horizontal infection between children at school. Moreover, in this study, there was one child with coexistence of HBsAg and anti-HBs antibody. In fact, several reports have shown a 2-10% incidence of this coexistence among chronic hepatitis B patients (Kwak et al. 2019; Jiang et al. 2021). Several explanations has been suggested; 1) infection with HBV immune escape mutant strain (Lada et al. 2006), 2) early phase of recovery, with both HBsAg and anti-HBs antibodies often found at low and transient levels, and 3) false positive test results (Kwak et al. 2019).

This study has some limitations. First, medical history and healthcare records of children were not available. This makes it difficult to track and verify the vaccination rate of study population. Second, the study population may not represent the precise vaccine response rate and HBV infection status among all hill-tribe children living in Chiang Mai. Nevertheless, this study may help point out the shortcomings of the HB vaccination policy among children living in remote areas. The results of this study can be used as evidence to improve HB vaccine policy in the future, particularly in remote areas.

CONCLUSION

HB vaccination has been integrated into the EPI for more than 20 years in Thailand. However, 14.1% of children living in Omkoi District, Chiangmai had markers of exposure to HBV and almost two-thirds of the children remained susceptible to HBV infection. This study reflects the problem of HB vaccination implementation among children living in remote areas. All hill-tribe children positive for HBsAg should be informed and provided with appropriate medical health care and treatment. For those negative for all HBV serological markers, HB vaccination should be provided properly and in a timely manner. In addition, children and people living in other rural areas should be assessed for HBV markers and receive appropriate care as necessary.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to all children who participated in this study and the teacher team for their management. We would like to thank all fourth-year students in medical technology program for handling blood collection and the IRD-UMI 174/PHPT laboratory team for providing workplace.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yada Aronthippaitoon: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, and writing – original draft. Nipatsorn Boonserm, Tunyalak Saming, Sucheewa Udomsilp: data curation and methodology. Sirinath Choyrum: data curation, methodology, and visualization. Sayamon Hongjaisee: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, resources, and writing – original draft. Jintana Yanola: resources. Nicole Ngo-Giang-Huong: project administration, supervision, and writing – original draft. Sakorn Pornprasert: funding acquisition, project administration, and supervision. Woottichai Khamduang: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, and writing – original draft. All authors have reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they hold no competing interests.

REFERENCES

Apidechkul, T., Laingoen, O., and Suwannaporn, S. 2016. inequity in accessing health care service in Thailand in 2015: a case study of the hill tribe people in Mae Fah Luang District, Chiang Rai, Thailand. Journal of Health Research. 30: 67-71.

Chongsrisawat, V., Yoocharoen, P., Theamboonlers, A., Tharmaphornpilas, P., Warinsathien, P., Sinlaparatsamee, S., Paupunwatana, S., Chaiear, K., Khwanjaipanich, S., and Poovorawan, Y. 2006. Hepatitis B seroprevalence in Thailand: 12 years after hepatitis B vaccine integration into the national expanded programme on immunization. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 11: 1496-502.

Hsu, S.C., Chang, M.H., Ni, Y.H., Hsu, H.Y., and Lee, C.Y. 1993. Horizontal transmission of hepatitis B virus in children. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 16: 66-9.

Jiang, Xinyi, Chang, L., Yan, Y., and Wang, L. 2021. Paradoxical HBsAg and anti-HBs coexistence among Chronic HBV Infections: Causes and Consequences. International journal of biological sciences. 17: 1125-37.

Jutavijittum, P., Jiviriyawat, Y., Yousukh, A., Hayashi, S., and Toriyama, K. 2005. Evaluation of a hepatitis B vaccination program in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 36: 207-12.

Keereekamsuk, T., Jiamton, S., Jareinpituk, S., and Kaewkungwal, J. 2007. Sexual behavior and HIV infection among pregnant hilltribe women in northern Thailand. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 38: 1061-9.

Khamduang, W., Ponchomcheun, N., Yaaupala, W., Puwaruengpat, P., Hongjaisee, S., Samleerat, T., Yanola, J., Pornprasert, S., Ratanasthien, K., Jourdain, G., et al. 2019. Serologic characteristics of hepatitis B virus among hill-tribe children in Omkoi district, Chiangmai province, Thailand. Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 13: 169-73.

Kwak, M.S., Chung, G.E., Yang, J.I., and Yim, J.Y. 2019. Long-term outcomes of HBsAg/anti-HBs double-positive versus HBsAg single-positive patients with chronic hepatitis B. Scientific Reports. 9: 19417.

Lada, O., Benhamou, Y., Poynard, T., and Thibault, V. 2006. Coexistence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBs Ag) and anti-HBs antibodies in chronic hepatitis B virus carriers: influence of "a" determinant variants. Journal of Virology. 80: 2968-75.

Lolekha, S., Warachit, B., Hirunyachote, A., Bowonkiratikachorn, P., West, D.J., and Poerschke, G. 2002. Protective efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine without HBIG in infants of HBeAg-positive carrier mothers in Thailand. Vaccine. 20: 3739-43.

Lukas, H. 2018. Southeast Asian hill tribes and the opium trade – The historical and social-economic background of the marginalization of minorities using the example of Thailand. Austria, Department of Geography and Regional Research, University of Vienna: 11-92.

McIntosh, E.D., Bek, M.D., Cardona, M., Goldston, K., Isaacs, D., Burgess, M.A., and E. Cossart, Y. 1997. Horizontal transmission of hepatitis B in a children's day-care centre: a preventable event. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 21: 791-2.

Meireles, Liliane C., Marinho, R.T., and Damme, P.V. 2015. Three decades of hepatitis B control with vaccination. World journal of hepatology. 7: 2127-32.

Pediatric Infectious Disease Society of Thailand. 2012. HBV immunization schedule recommendations in Thailand. 2012. Accessed 28 February, from http://www.healthcaremedicalclinic.com/pdf/pdf11.pdf.

Pichainarong, N., Chaveepojnkamjorn, W., Luksamijarulkul, P., Sujirarat, D., and Keereecamsuk, T. 2003. Hepatitis B carrier among married hilltribe women in northern Thailand. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 34: 114-9.

Poovorawan, Y., Theamboonlers, A., Vimolket, T., Sinlaparatsamee, S., Chaiear, K., Siraprapasiri, T., Khwanjaipanich, S., Owatanapanich, S., Hirsch, P., and Chunsuttiwat, S. 2000. Impact of hepatitis B immunisation as part of the EPI. Vaccine. 19: 943-9.

Saso, A. and Kampmann, B. 2017. Vaccine responses in newborns. Semin Immunopathol. 39: 627-42.

Verso, M.G., Costantino, C., Vitale, F., and Amodio, E. 2019. Immunization against Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HBsAg) in a Cohort of Nursing Students Two Decades after Vaccination: Surprising Feedback. Vaccines. 8.

Wang, B., Xu, X.X., Wen, H.X., Hao, H.Y., Yang, Z.Q., Shi, X.H., Fu, Z.D., Wang, X.F., Zhang, F., Wang, B., and Wang, S.P. 2017. Influencing factors for non/low-response to hepatitis-B vaccine in infants of HBsAg positive mothers. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 38: 911-15.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2021. Hepatitis B: fact sheets. Accessed 2 November, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b.

World Health Organizaton (WHO). 2019. WHO and UNICEF estimates of immunization coverage: 2019 revision. from https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/tha.pdf.

Yang, Z.Q., Hao, H.Y., Shi, X.H., Fu, Z.D., Zhang, F., Wang, X.F., Xu, X.X., Wang, B., X. Wen, H., Feng, S.Y., Wang, B., and Wang, S.P. 2018. Relationship between the HBsAg-positive infection status of mothers and the non/low-response to hepatitis B vaccine of their infants. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 39: 805-09.

Yanola, J., Nachaiwieng, W., Duangmano, S., Prasannarong, M., Somboon, P., and Pornprasert, S. 2018. Current prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and their impact on hematological and nutritional status among Karen hill tribe children in Omkoi District, Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. Acta Tropica. 180: 1-6.

Yeung, L.T. and Roberts, E.A. 2001. Hepatitis B in childhood: An update for the paediatrician. Paediatrics & child health. 6: 655-59.

OPEN access freely available online

Chiang Mai University Journal of Natural Sciences [ISSN 16851994]

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Yada Aronthippaitoon1, Nipatsorn Boonserm1, Tunyalak Saming1, Sucheewa Udomsilp1, Sirinath Choyrum1, Sayamon Hongjaisee2, Jintana Yanola1, Nicole Ngo-Giang-Huong3,4, Sakorn Pornprasert1, and Woottichai Khamduang1,4, *

1 Department of Medical Technology, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiangmai, Thailand

2 Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiangmai, Thailand

3 Infectious Diseases and Vectors : Ecology, Genetics, Evolution and Control (MIVEGEC), Agropolis University Montpellier, French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD), 34394 Montpellier, France

4 Associated Medical Sciences (AMS)-PHPT Research Collaboration, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand

Corresponding author: Woottichai Khamduang, E-mail: woottichai.k@cmu.ac.th

Total Article Views

Editor: Korakot Nganvongpanit,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: January 11, 2022;

Revised: March 14, 2022;

Accepted: March 17, 2022;

Published online: April 5, 2022