Survival Analysis of Time to Death of HIV-Infected Patients under Antiretroviral Therapy in Tepi General Hospital, South West Ethiopia

Alemu Bekele EtichaPublished Date : 2021-09-13

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/CMUJNS.2021.092

Journal Issues : Number 4, October-December 2021

Abstract Despite advancements in HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment, HIV continues to be a global problem. Antiretroviral therapy is a critical treatment that has been used to treat HIV-infected patients since 1996. Even though an increase in the number of patients enrolled in ART, the mortality rate for HIV cases in Ethiopia has never been overcome. Thus, this study aimed to identify influential factors of death of HIV-infected individuals received antiretroviral therapy at the Tepi General Hospital. The secondary data was extracted from each selected patient for whom the ART was initiated from September 2011 to June 2018. Then, Cox regression technique provided the essential determinants of time to death of HIV-infected patients. The findings revealed that 35.14 percent of HIV patients died despite being on ART. The identified causes of death were being over 40 years old, being in clinical stage IV, being uneducated, having a low body weight, and having a low CD4 cell count. Gender, tuberculosis status, and functional status, on the other hand, were not supported as factors. Thus, age over 40 years, being underweight, having a low baseline CD4 cell count, being in an advanced WHO clinical stage, and having a low education level were identified as critical risk factors that exposed to early death even while on ART. As a result, the hospital advised prioritizing patients based on the identified factors.

Keywords: AIDS; Analysis; Biological modeling; Biological activities

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this paper. However, the material support received from institutions of the author.

Citation: Eticha, A.B. 2021. Survival analysis of time to death of HIV-infected patients under antiretroviral therapy in Tepi general hospital, south west Ethiopia. CMU J. Nat. Sci. 20(4): e2021092.

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is one of the worldwide pandemic infectious diseases, posing major challenges to human survival. HIV/AIDS is troubles and challenges individuals still because it is a non-cure disease (Hopkin, 2008). However, medication can extend only the lifetime of infected people. The ultimate important treatment that can diagnose HIV/AIDS is called Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) (Nakagawa et al., 2012). ART is the most serious strategy that extended lives and reduced the transmission of the HIV disease from infected to uninfected people (Federal HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office, 2018). This means, ART can keep HIV-infected individuals healthy for several years and significantly reduce the transmission of HIV to normal person (Girum et al., 2018).

This strategy brought diagrammatic change among those living with HIV in developed countries, but it only reached a part of individuals in low-income countries (Mengesha et al., 2014). The pharmacological activity of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) is inhibitory effects on HIV replication and has shown a significant reduction in AIDS epidemics death in prosperous countries (Tezera et al., 2014). On the other hand, the highest number of deaths occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa countries reported after antiretroviral therapy was implemented in 1996. However, a few declines in the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in some Sub-Saharan African countries have been reported recently (Young et al., 2014).

The first HIV/AIDS case in Ethiopia was detected in 1984 and the first two cases were reported in 1986 (Khodakevich et al., 1990). Since then, the epidemic has spread to the overall population in both urban and rural areas. The HIV/AIDS was the leading reason for morbidity and mortality among adults in Ethiopia (Hladik et al., 2006). According to the Federal HIV/AIDS prevention report, about 722, 248 people were living with HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia with the rate of prevalence 0.90% in 2017 (Kibret et al., 2019). The AIDS-related deaths reduced from 83,000 deaths in 2000 to 15,600 in 2017. In 2018 in Ethiopia, number of ART treatment failure was 15.9% (Mulisa et al., 2019). Even though the number of patients enrolled in ART is increased from time to time, incidents of HIV/AIDS continue to constitute a significant proportion of health reports in Ethiopia (Mishore et al., 2020). Thus, the risk of mortality in low-income countries like Ethiopia needs additional studies on primary prevention methods (Federal HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office, 2018).

The study from the Oromia region verified that HIV patients with poor resource situations are still dying even if they are on ART treatments (Seyoum et al., 2017). The study from Brazil supported factors of mortality rates on peoples living with HIV were demographic and behavioral factors (Mangal et al., 2019). Another scholar revealed the factors that cause death during antiretroviral therapy as tuberculosis status, a lower amount of CD4, being underweight, being a merchant, and being on WHO clinical stage IV (Tadege, 2018). In another study from North Ethiopia, rural residence, lower CD4 cell values, and having unscheduled follow-up were predictors of an increased likelihood of the cause mortality (Yirdaw and Wencheko 2015). In spite of different scholars reported different determinants of death for their study, this study intended to identify more factors related to survival time under ART in Tepi General Hospital (TGH). Moreover, this study was conducted in the most prevalence-rated area of the country (Federal HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office, 2018).

According to the empirical literature, the statistical method confirmed to identify risk factors of time to death of HIV-infected person is survival techniques (Tezera et al., 2014; Seyoum et al., 2017; Mangal et al., 2019; Tadege, 2018; Yirdaw and Wencheko, 2015; Atey et al., 2020). Thus, the most popularly used survival method, Cox regression practiced in this study to distinguish significant factors of time to death of patients with HIV-infected in southwest Ethiopia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Area and Period

The study was conducted in Tepi General Hospital which is the only hospital in the Shaka zone, southwest Ethiopia. It is 611 kilometers far apart from Addis Ababa capital city of Ethiopia. The hospital delivers care services for whole residents in the Sheka Zone, partially Majang zone (Gambella region), Bench-Shako zone, and partially Kaffa zone. The study period was considered from September 2011 to June 30, 2018. Thus, patient data, September 30, 2011, up to June 30, 2018, were considered as information gathered in a given study time.

Study design

The retrospective cohort study design was applied to HIV-infected individuals that were initiated under ART treatment and followed at Tepi General Hospital. The privacy information of each of the patient was removed and confidential before the study started and then, secondary data was extracted from 74 HIV patients at TGH.

Source and study population: All patients who attended ART in Tepi General Hospital were considered as the source population whereas all sampled individuals were considered as the study population.

Study variables: The outcome variable of this study was the survival time of HIV-infected patients of ART start date until death in months. However, HIV-infected patients, who stayed alive during the study time or lost or dropped or died by other cases, were considered as right-censored. In addition, explanatory variables that are considered under the study were; sex (Male, Female), age category in years (less than 30, 30-39, 40-49, more than 50), baseline CD4 count; baseline body weight; baseline TB screen result (negative, positive), level of education (Illiterate, elementary school, Secondary and above), WHO clinical stage (stage-I, stage-II, stage-III, stage-IV) and performance status (working: able to perform usual work in or out of the house and ambulatory: ready to perform activities of daily living, bedridden: unable to perform activities of living daily).

Survival Analysis

Survival analysis provides special systems that are required to compare the risks for death associated with different groups, where the risk changes over time. This special feature of the survival method is the issue of censoring which occurs when the time for a few individuals cannot be completely observed (Bewick et al., 2004; Collett, 2015). An observation is claimed to be right censoring if it is recorded from its beginning until a well-defined time. In analyzing survival data there are two common functions; the survivor function and the hazard function (David and Hosmer, 1999). Kaplan–Meier estimators were applied to display the survival experience of patient’s overtime for qualitative predictor variables and a log-rank test was applied to check whether there is a significant difference between predictor variables towards the survival capacity of patients. Moreover, Cox proportional hazard model was accustomed to identifying the numerous effect of every variable of the time to death event (Collett, 2015). Thus, the Proportional Hazard function h(t) is decided by a group of k variables X1, X2, …, Xk, whose influence is measured by the dimensions of the respective coefficients β1, β2, …, βk;

![]()

Where h0(t) is termed the baseline hazard for a time to die.

The proportionality assumptions of the Cox proportional model must satisfy as a guarantee on each predictor and on the overall test of proportionality. This means that none of the predictors failed the Cox proportional hazard assumption. The results of the Wald test and Likelihood test had used to reject predictor variables with a P-value lower than 0.05 (Tadege, 2018).

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

A brief exploration of the patients included in the study was as follows. Based on ‘Table 1’, 36(48.65%) female and 38(51.35%) male patients within the retrospective cohort study out of which 26(35.14%) died, and the remaining 48(64.86%) were censored.

In the age category; 22(29.70%), 27(36.48%), 12(16.20%), and 13(5.80%) of patients were age below 30 years, 30-39 years, 40-49 years, and above 50 years, respectively. Regarding tuberculosis co-morbidity, 38(51.40%) of patients were TB screen positive and 36(48.60%) of patients were TB screen negative. Concerning the WHO clinical stage; 19(25.60%), 17(22.90%), 25(41.89%), and 13(17.56%) of patients were stage I, II, III, and IV, respectively. Concerning education level; 24(32.43%), 26(35.13%), and 24(32.43%) of patients were uneducated, primary school and secondary school, respectively. In the case of functional status; 17(22.97%), 23(31.08%) and 34(45.95%) of patients were working, ambulatory and bedridden respectively.

Furthermore, 46.15% TB negative and 53.85% TB positive deaths; identical 50.00% death in both gender; 19.23%, 19.23%, 38.46%, 23.08% deaths in clinical stages I-IV respectively; 50.00%, 30.77%, and 19.23% deaths recorded were bedridden, ambulatory and working respectively displayed.

Table 1. Results of descriptive statistics for categorical variables of HIV infected adult patients in Tepi General Hospital, 2018.

|

Variable |

Categories |

Status of Patients |

||

|

Censored (%) |

Died (%) |

Total (%) |

||

|

Age Category

|

15(20.27%) |

7(9.46%) |

22(29.73%) |

|

|

30-39 years |

18(24.32%) |

9(12.16%) |

27 (36.48)% |

|

|

40-49 years |

5(6.76%) |

7 (9.46%) |

12 (16.22%) |

|

|

>50 years |

10(13.51%) |

3 (4.05%) |

13 (17.57%) |

|

|

Total |

48(64.86%) |

26(35.14%) |

74(100%) |

|

|

Functional status

|

Working |

12(16.22%) |

5(6.76%) |

17(22.97%) |

|

Ambulatory |

15(20.27%) |

8(10.81%) |

23(31.08%) |

|

|

Bed ridden |

21(28.38%) |

13(17.57%) |

34(45.95%) |

|

|

Total |

48(64.86%) |

26(35.14%) |

74(100%) |

|

|

TB Result

|

Positive |

26(35.14%) |

12(16.22%) |

38(51.36%) |

|

Negative |

22(29.72%) |

14 (18.92%) |

36(48.64%) |

|

|

Total |

48(64.86%) |

26(35.14%) |

74(100%) |

|

|

Opportunistic Infections |

No |

12 (16.22%) |

9(12.16%) |

21(28.38%) |

|

Yes |

36(48.65%) |

17(22.97%) |

53(71.62%) |

|

|

Total |

48(64.86%) |

26(35.14%) |

74(100%) |

|

|

WHO clinical stage

|

Stage I |

14(18.92%) |

5(6.76%) |

19(25.68%) |

|

Stage II |

12(716.22%) |

5(6.76%) |

17(22.97%) |

|

|

Stage III |

15(20.27%) |

10(13.51%) |

25(33.78%) |

|

|

Stage IV |

7(9.46%) |

6(8.11%) |

13(17.57%) |

|

|

Total |

48(64.86%) |

26(35.14%) |

74(100%) |

|

|

Gender

|

Female |

23(31.08%) |

13(17.57%) |

36 (48.65%) |

|

Male |

25(33.78%) |

13 (17.57%) |

38(51.35%) |

|

|

Total |

48(64.86%) |

26(35.14%) |

74(100%) |

|

|

Educational level

|

Illiterate |

11 (14.86%) |

13(17.57)% |

24(32.43)% |

|

Primary school |

17(22.97%) |

9(12.16%) |

26(35.14%) |

|

|

>Secondary |

20(27.03%) |

4(5.41%) |

24(32.43%) |

|

|

Total |

48(64.86%) |

26(35.14%) |

74(100%) |

|

According to (Table 2) the median baseline CD4 cell and median weight of patient’s were 200.00 Cells/l and 49.00kg, respectively, with a median survival time of 46.5 months. Similarly, when ART treatment was initiated, the average CD4 cell count and the average weight of patient’s were 193 cells/l and 49.66kg, respectively, with an average survival time of 48.58 months. The shortest survival time was 20 months, and the longest survival time was 89 months. Lastly, the distribution of CD4, weight and time were 200(73), 49(74) and 46.5(74) respectively.

Table 2. Summary of descriptive statistics for continuous variables of HIV infected adult and adolescent patients in Tepi General Hospital

|

Statistic |

Baseline CD4 (Cell/μl) |

Baseline weight(Kg) |

Survival time |

|

Q1 |

182.00 |

30.50 |

28.00 |

|

Median |

200.00 |

49.00 |

46.50 |

|

Q3 |

255.00 |

104.50 |

102.00 |

|

Median (Q3-Q1) |

200.00 |

49.00 |

46.50 |

|

Mean |

193.38 |

49.66 |

48.58 |

|

Mode |

200.00 |

48.00 |

36.00 |

|

Minimum |

78.00 |

13.00 |

20.00 |

|

Maximum |

380.00 |

70.00 |

89.00 |

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves

The common predictor variable’s survival curves were displayed under this sub section. The Kaplan-Meier curve according to clinical stage, Education level, age category, TB status, gender, opportunistic disease and functional status were displayed in this study.

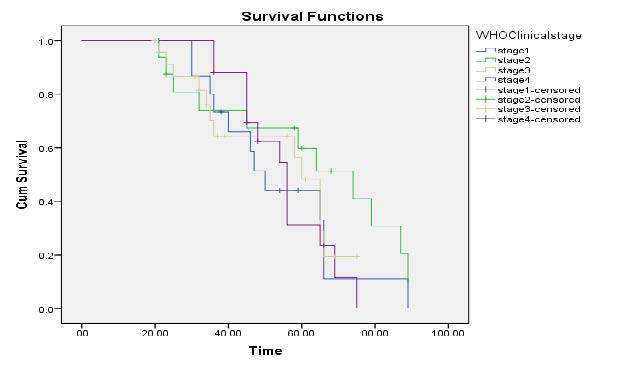

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves on Clinical stage: Figure 1, indicated that WHO Clinical Stages IV is more at risk of death because it has the least survival time. Thus, a fourth clinical stage and a first clinical stage had lower survival times of HIV- infected patients related to a second and a third clinical stage.

Figure 1 Kaplan-Meier curves of WHO clinical Stages.

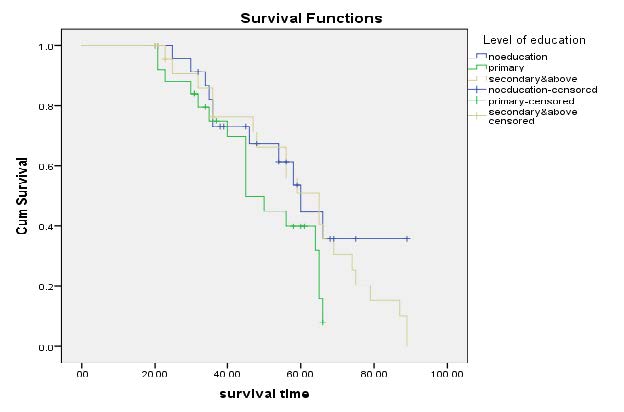

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves on Level of Education: Figure 2, displayed that uneducated and primary educated survivor is lower than secondary and high school. According to the displayed curve, the risk of death is more on educated patients.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier curves on level of educations of HIV patients at Tepi General Hospital.

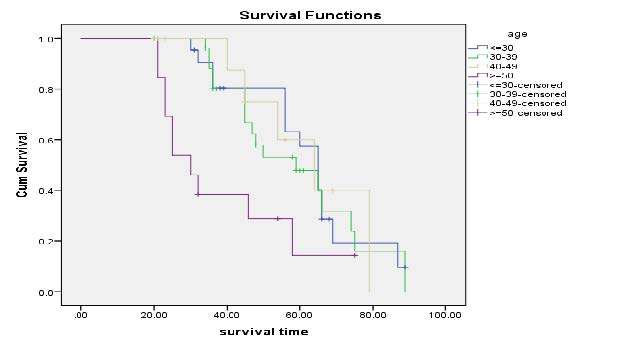

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves on Age category: Figure 3 explored that age category more than 50 belong to lower survival time. The age category seems non-proportional. Thus, older age has a higher risk of death. Higher numbers of patients are censored during the age of 30-39 and a lower number of patients is censored in the age of greater than or equal to 50 years old.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier curves on Age category.

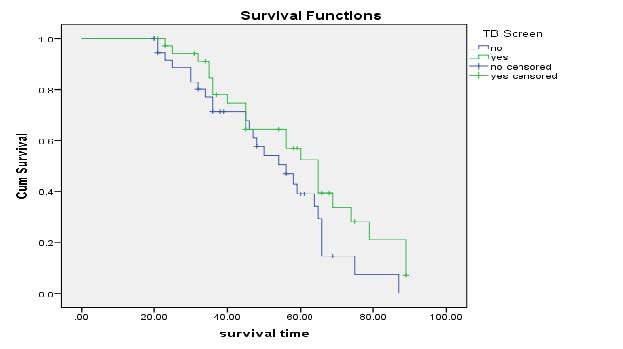

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves on TB Co-morbidity: Figure 4 displayed these unscreened for TB has lower survival time than that of patients who treated for their tuberculosis. According to Kaplan-curve treating for TB enhances the survival time of patients since the risk of death was high in non TB screened.

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier curves of TB screen Result.

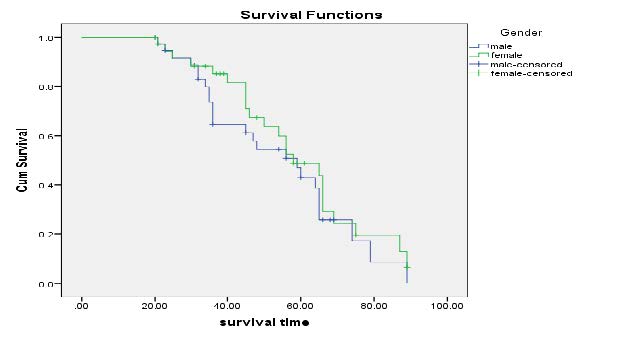

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves on Gender: Figure 5 displayed that survival time for males are slightly lower than males. The survival time is similar for both male & female at the beginning of and end of curve. However, at centre of the curve the survival plot of male is lower than female.

Figure 5. Kaplan-Meier curves of Gender.

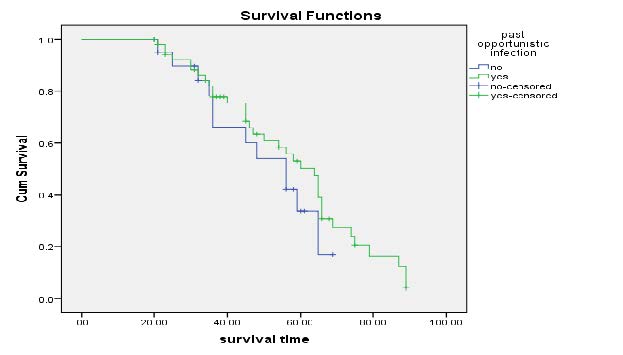

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves on past opportunistic infection: Figure 6 illustrate that survival time for past opportunistic is identical up to 20th moth and vary as approached to 30 months.

Figure 6. Kaplan-Meier curves of Past opportunistic Infection.

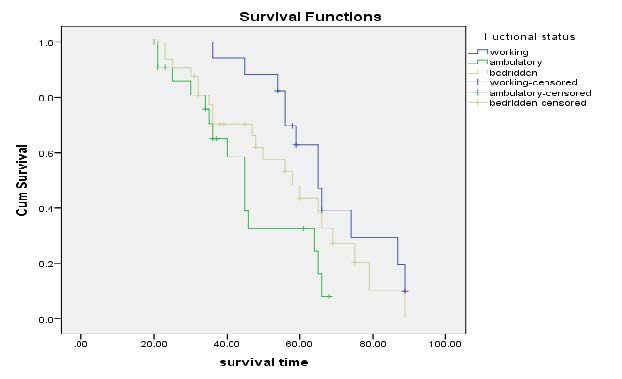

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves on functional status: Figure 7 illustrate that survival time for functional status of ambulatory class was lower than working or bedridden. From the curve we observe that the mean live of patient constantly decrease at the first month and finally increase as month increase.

Figure 7. Kaplan-Meier curves of Functional Status.

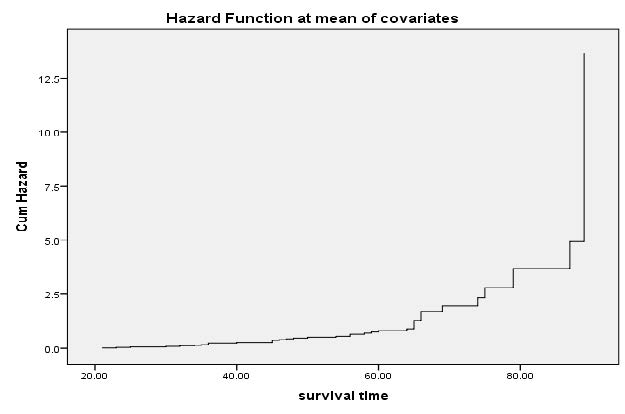

Figure 8 indicates the risk trend of HIV-infected patients at Tepi general hospital. This curve illustrate that the risk of death increased with time slightly starting from 20 months up to end.

Figure 8. Hazard function curves of HIV survival data in Tepi General Hospital, 2018.

Log-rank test

The Log-rank test and the univariate Cox regression were used for the inclusion criteria of predictor variables. For the specific variables, we used the log-rank test of equality across a stratum which is a non-parametric test. Each variable was included in the model if the log-rank test’s P-value less than 0.05. As a result, the log-rank test yielded the following p-values for age, functional status, TB status, clinical stage, gender, and education level: <0.001, <0.001, <0.001, <0.001, 0.485, and

Cox Regression Results

A preliminary Univariate analysis revealed that age, functional status, baseline clinical stage, baseline CD4 count, TB status, education level, and baseline weight were all significantly related to a patient's survival time. The Cox regression, on the other hand, identified additional multiple factors on survival time. Age less than 30 years, working functional status, negative TB screen result, non previous opportunistic infections, clinical stage-I, and illiteracy of the educational level were considered as references in the model building.

Based on ‘Table 3’, in Cox multivariate regression, we have strong evidence that age, baseline weight, baseline CD4 cell count, clinical stage, and education level were associated with length of survival.

In particular, a baseline weight of the patient had a hazard ratio (HR = 0.95 at 95 percent CI (0.93, 0.97), indicated that a kilogram increase in weight leads to a 4.56 percent reduction in hazard ratio for all other factors controlled. In other words, if the value of weight increased by 1 unit, the risk of death decreases by 0.045. The coefficient for body weight, -0.046 is logarithm of hazard ratio for patient given all other variables fixed.

The exponential of the coefficient for CD4 count is 0.99, indicates that a patient a unit more than another patient, both being given the same on all other factors, has a decrease risk for dying, by a factor of 0.04. In the same way, if baseline CD4 count of the patient increased by one cell/μl, then the hazard ratio decreased by 0.41 percent while all other variables remained constant. Since baseline CD4 cell coefficient is negative the number of baseline CD4 cell and risk of death were inversely related. As a result, survival time increased when CD4 count increased and decreased when CD4 count declined.

As shown in (Table 3), the age groups 40 to 49 years and over 50 years were statistically significant in terms of survival time. The hazard ratio indicates that patients over the age of 40 are more likely to die than those under the age of 30 years. Obviously, the risk of death for HIV-infected patients aged 40 to 50 years was 4.89 times higher than for those aged less than 30 years. Similarly, the risks of death for HIV-infected individuals over 50 years of age are 5.39 times higher than for those under 30 years of age.

In terms of clinical stage, the only significant category is clinical stage IV (P-value=0.003). The risk of death for HIV-infected patients in clinical stage IV was 5.16 times higher than for HIV-infected patients in clinical stage I. As a result, clinical-stage IV duration was shorter than clinical stage I survival time.

Finally, education levels higher than primary school are significant for survival time. Because the p-values for primary and secondary schools were 0.016 and 0.007, respectively, they were less than the 5% level of significance. Furthermore, HIV patients who went to primary school had a lower risk of death than illiterates. A hazard ratio of 0.44 for primary educated HIV patients indicated that primary educated patients had a 43.98 percent lower risk of death than uneducated patients. Similarly, the hazard ratio of secondary educated level patients was 0.42, indicating that secondary and above educated patients were 42.09 percent less likely to die than illiterate patients.

Table 3. Result of multivariate Cox regression analysis of HIV infected patients under ART at Tepi General Hospital, 2018.

|

Variable name |

Variable code |

Hazard Ratio/HR |

Coefficient b |

Standard Error |

Wald |

P-value |

95% CI HR |

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

|||||||

|

Age |

[30-39] years |

1.93 |

0.66 |

0.99 |

1.29 |

0.197 |

0.71 |

5.26 |

|

[40-49] years |

4.89 |

1.59 |

2.49 |

3.12 |

0.002 |

1.81 |

13.27* |

|

|

>50 years |

5.39 |

1.68 |

2.752 |

3.30 |

<0.001 |

1.98 |

14.66* |

|

|

Body weight |

Baseline |

0.95 |

-0.05 |

0.01 |

-3.95 |

<0.001 |

0.93 |

0.97* |

|

CD4 Count |

Baseline CD4 |

0.99 |

-0.03 |

0.01 |

-2.42 |

0.016 |

0.99 |

0.99* |

|

Clinical Stage |

Stage-II |

0.77 |

-0.25 |

0.52 |

-0.38 |

0.705 |

0.21 |

2.89 |

|

Stage-III |

2.45 |

0.898 |

1.35 |

1.63 |

0.102 |

0.83 |

7.21 |

|

|

Stage-IV |

5.16 |

1.64 |

2.86 |

2.96 |

0.003 |

1.74 |

15.32* |

|

|

Education level |

Primary |

0.44 |

-0.82 |

0.15 |

-2.42 |

0.016 |

0.23 |

0.86 |

|

Secondary |

0.42 |

-0.86 |

0.14 |

-2.68 |

0.007 |

0.22 |

0.79 |

|

|

Functional status |

Ambulatory |

1.81 |

0.59 |

0.61 |

1.75 |

0.080 |

0.93 |

3.51 |

|

Bed ridden |

1.67 |

0.511 |

0.66 |

1.3 |

0.195 |

0.77 |

3.61 |

|

|

TB Screen |

TB status |

1.93 |

0.66 |

0.702 |

1.81 |

0.071 |

0.95 |

3.94 |

|

Other disease |

Opportunistic |

1.32 |

0.28 |

0.51 |

0.73 |

0.462 |

0.63 |

2.79 |

Proportionality of Cox-Regression

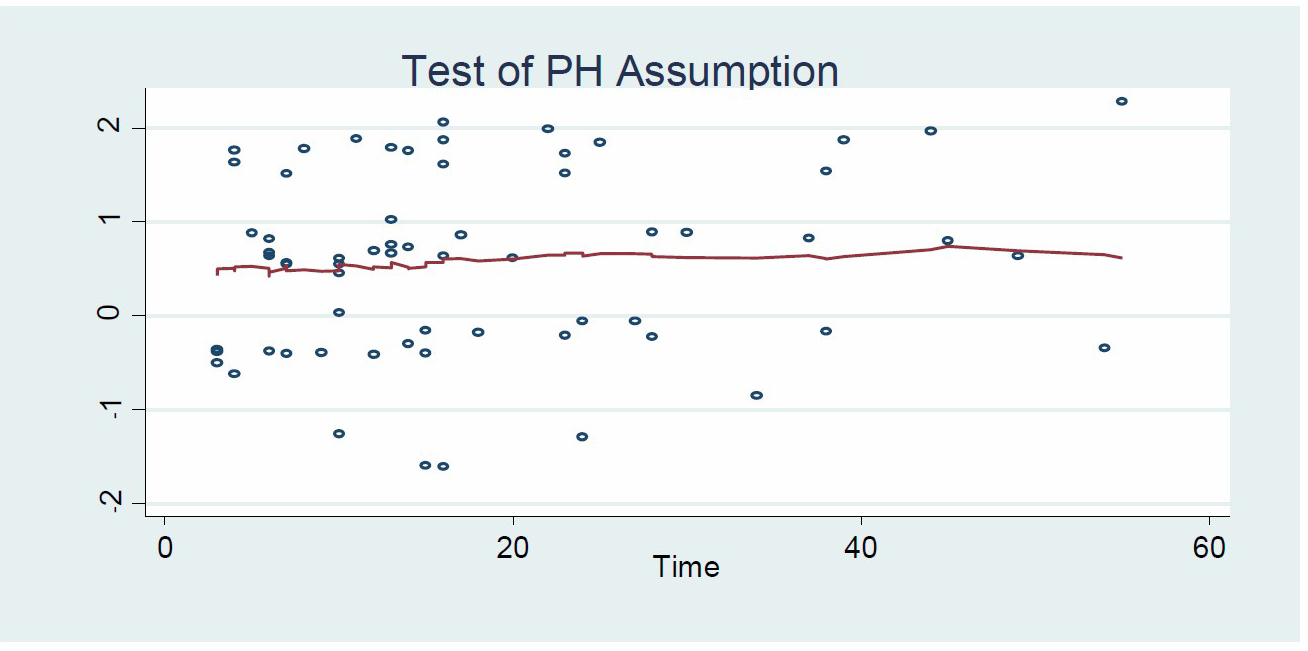

Schoenfeld residuals applied to check proportionality assumption of Cox Regression. If test were not significance (P-values over 0.05) then we could not reject proportionality and we assumed that we do not have a violation of the proportional assumption. Thus, proportional hazard ratio assumption of Cox regression is obtained since the P-values are over the significance level value 0.05. As a result, we ensured that no violation of the proportional assumption occurred (Table 4).

Table 4. Result of Proportional hazard assumption test of HIV infected patients under ART at Tepi General Hospital, 2018.

|

Variable |

Chi-square |

Degree freedom |

P-value |

|

Age |

1.49 |

1 |

0.22 |

|

Baseline weight |

0.02 |

1 |

0.874 |

|

Baseline CD4 |

5.99 |

1 |

0.144 |

|

WHO clinical stage |

0.65 |

3 |

0.419 |

|

Education level |

0.21 |

2 |

0.646 |

|

Global test |

9.21 |

5 |

0.103 |

Figure 9 demonstrated that a horizontal line in the graphs did not violate the proportionality assumption.

Figure 9. Graph of proportional hazard assumption.

DISCUSSION

This seven-year retrospective cohort study of HIV/AIDS patients on ART provides information on survival and its determinants in the perspective of a Tepi General Hospital. In this cohort, 35.14% of the patients died. This overall mortality rate was higher than other studies in Ethiopia, where it was found to be 10.3% and 20.3% in southwest Ethiopia (Alemu and Sebastián, 2010; Setegn et al., 2015). The reason could be that the study area had a high prevalence of disease, making it difficult to distribute health equipment. Furthermore, the death rate was higher in related to other studies in Africa, where it was found to be 29.7% in Tanzania and 23% in Cameroon, respectively (Johannessen et al., 2008; Sieleunou et al., 2009).

The causes of death in HIV-infected patients on ART at Tepi General Hospital have been identified. These variables included the patient's age, clinical stage, educational level, baseline body weight, and baseline CD4 count. This finding was supported by other studies conducted in Ethiopia and other countries (Mengesha et al., 2014; Tadege, 2018; Mangal et al., 2019; Mirzaei et al., 2019). Moreover, the Oromia's study stated TB status (Mishore et al., 2020; Tadege, 2018), whereas other studies claimed gender, tuberculosis status, baseline functional status, anemia status, and adherence to ART in capital city Addis Ababa (Mengesha et al., 2014). Other continents' studies confirmed the causes of mortality associated with age, gender, residence, ART use, TB status, and CD4 from Brazil or Iran (Mangal et al., 2019; Mirzaei et al., 2019).

Unlike other researchers, this study did not support TB status, gender, functional status, or opportunistic disease (Teklu et al., 2017; Tadege, 2018). The significance of gender in determining the survival time to death was stated in many studies (Melo et al., 2008; Yirdaw and Wencheko, 2015; Mangal et al., 2019; Mirzaei et al., 2019). However, this study did not confirm gender as a determinant of survival time to death in agreement with studies (Mengesha et al., 2014; Seyoum et al., 2017; Mishore et al., 2020). Among possible reasons for the gender difference, it has been suggested that female patients tend to understand their HIV status at an earlier stage and follow antiretroviral therapy as males (Seyoum et al., 2017; Ethiopian Public Health Institute, 2020). Unlike previous studies (Yirdaw and Wencheko, 2015; Tadege, 2018; Teklu, 2018; Mirzaei et al., 2019), this study found no link between TB status and survival time. The reason for this could be that TB-HIV patients may receive TB treatment (Melo et al., 2008; Setegn et al., 2015; Seyoum et al., 2017).

This study confirmed that the WHO clinical stage was a determinant of mortality in patients who received ART, as previously demonstrated (Mengesha et al., 2014; Tezera et al., 2014; Abebe et al., 2016; Teklu et al., 2017). In the same way, this study found that the WHO clinical stage IV was the main determinant of death in the case of HIV/AIDS. The study discovered that patients who started ART at an advanced disease stage were five times more likely to die than those who started it at an early clinical stage. Indirectly, HIV-infected patients must undergo testing and receive ART as soon as possible to increase their chances of survival.

The other predictor of mortality was low CD4 cell. According to the findings of this study, patients with a lower CD4 count have a higher risk of death than those with a higher CD4 count. This finding was supported by other researchers (Tadege, 2018; Mangal et al., 2019; Mirzaei et al., 2019; Mishore et al., 2020). Beside that, this study discovered that individuals who began the ART with a low baseline weight had a higher risk of death. The successive weights measure was used to predict treatment outcomes (Seyoum et al., 2017; Tadege, 2018). As a result, patients with a low CD4 cell count and a low body weight at baseline require special attention and care.

Another important factor in mortality was the age of HIV-infected patients. Almost identical to this study, age of patients was confirmed by other researchers (Seyoum et al., 2017; Teklu et al., 2017; Mangal et al., 2019; Mulisa et al., 2019). The age over 40 years were more vulnerable to death. Additionally similar to Abebe, et al., 2019, education level was confirmed as a risk factor for death. This means, educated individuals can more attend instructions of treatments.

This study discovered that being older than 40, being in an advanced WHO clinical stage, having a low baseline CD4 count, having a low baseline body weight, and having a low education level were all significant predictors of death. However, the ART alone cannot account for all of the improvement in survival of patients. Since more patients with HIV are able to keep their infections under control, doctors are focusing more on also CD4, weight and education.

CONCLUSION

This study calculated the survival time of HIV-infected patients who received ART at Tepi General Hospital and identified factors that contributed to death. Age over 40, low baseline weight, low baseline CD4 cell count, base line clinical stage IV, and low educational level were discovered to be significant factors for time to death in the case of HIV/AIDS. As a result, the concerned bodies must provide care support for every identified influential factor in order to increase patient survival and reduce disease prevalence. Better healthcare overall for HIV patients is also serving them to live longer.

The extra study may suggest on TB co-morbidity effect and sex difference since it contradicts to some scholars. Moreover, Meta-analysis was suggested for future research because researchers disagreed on these causes of death.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thanks Tepi General Hospital because they had given the data used under the study and great thanks to Mizan-Tepi University because of materials support.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

An author is confidentially doing all phases of preparation of the manuscript ranging from the start of the project, collection of data, analysis of data, and interpretation of results and writing of the manuscript. The manuscript was original.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This finding was approved by the Institution of the author and announced to the institution of the info source before the study began. The privacy information of every of the patient was removed before the study started. I strongly assure that the study hart no patient because the secondary data was used under the paper from the patient’s chart.

REFERENCES

Abebe, T.W., Chaka, T.E., Misgana, G.M., and Adlo, A.M., 2016. Determinants of survival among adults on antiretroviral therapy in Adama Hospital Medical College, Oromia Regional state, Ethiopia. Journal HIV AIDS, 2.

Alemu, A.W. and Sebastián, M.S., 2010. Determinants of survival in adult HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy in Oromiyaa, Ethiopia. Global health action, 3: 5398.

Atey, T.M., Bitew, H., Asgedom, S.W., Endrias, A., and Berhe, D.F., 2020. Does isoniazid preventive therapy provide better treatment outcomes in HIV-infected individuals in northern Ethiopia? A retrospective cohort study. AIDS Research and Treatment, 2020: 1-11.

Bewick, V., Cheek, L. and Ball, J., 2004. Statistics review 12: survival analysis. Critical care, 8: 1-6.

Collett, D., 2015. Modelling survival data in medical research. CRC press.

David, W. and Hosmer, L., 1999. Applied survival analysis: regression modeling of time to event data. Wiley-Interscience.

Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI), 2020. Ethiopia Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (EPHIA) 2017-2018: Final Report. Addis Ababa: EPHI.

Federal HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office, 2018. HIV Prevention in Ethiopia National Road Map.

Gillespie, S. and Gillespie, S.R. eds., 2006. AIDS, poverty, and hunger: Challenges and responses. Intl Food Policy Res Inst.

Girum, T., Wasie, A., and Worku, A., 2018. Trend of HIV/AIDS for the last 26 years and predicting achievement of the 90–90-90 HIV prevention targets by 2020 in Ethiopia: a time series analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases, 18: 1-10

Hladik, W., Shabbir, I., Jelaludin, A., Woldu, A., Tsehaynesh, M., and Tadesse, W., 2006. HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia: where is the epidemic heading?. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 82: i32-i35.

Hopkin, M., 2008. HIV can'never be cured'.

Johannessen, A., Naman, E., Ngowi, B.J., Sandvik, L., Matee, M.I., Aglen, H.E., Gundersen, S.G., and Bruun, J.N., 2008. Predictors of mortality in HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy in a rural hospital in Tanzania. BMC Infectious Diseases, 8: 1-10.

Khodakevich, L., Mehret, M., Negassa, H. and Shanko, B., 1990. Projections on the development of HIV/AIDS epidemics in Ethopia. The Ethiopian Journal of Health Development, 4.

Kibret, G.D., Ferede, A., Leshargie, C.T., Wagnew, F., Ketema, D.B., and Alebel, A., 2019. Trends and spatial distributions of HIV prevalence in Ethiopia. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 8: 1-9.

Mangal, T.D., Meireles, M.V., Pascom, A.R.P., de Almeida Coelho, R., Benzaken, A.S., and Hallett, T.B., 2019. Determinants of survival of people living with HIV/AIDS on antiretroviral therapy in Brazil 2006–2015. BMC Infectious Diseases, 19: 1-9.

Melo, L.S.W.D., Lacerda, H.R., Campelo, E., Moraes, E., and Ximenes, R.A.D.A., 2008. Survival of AIDS patients and characteristics of those who died over eight years of highly active antiretroviral therapy, at a referral center in northeast Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 12: 269-277.

Mengesha, S., Belayihun, B., and Kumie, A., 2014. Predictors of survival in HIV-infected patient after Initiation of HAART in Zewditu Memorial Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2014: 1-6.

Mirzaei, M., Farhadian, M., Poorolajal, J., Kazerooni, P.A., Tayeri, K., and Mohammadi, Y., 2019. Survival rate and the determinants of progression from HIV to AIDS and from AIDS to the death in Iran: 1987 to 2016. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine, 12: 72.

Mishore, K.M., Hussein, N., and Huluka, S.A., 2020. Hospitalization and predictors of inpatient mortality among HIV-infected patients in Jimma University specialized hospital, Jimma, Ethiopia: prospective observational study. AIDS Research and Treatment, 2020: 1872358

Mulisa, D., Tesfa, M., Kassa, G.M., and Tolossa, T., 2019. Determinants of first line antiretroviral therapy treatment failure among adult patients on ART at central Ethiopia: un-matched case control study. BMC Infectious Diseases, 19: 1-13.

Nakagawa, F., Lodwick, R.K., Smith, C.J., Smith, R., Cambiano, V., Lundgren, J.D., Delpech, V., and Phillips, A.N., 2012. Projected life expectancy of people with HIV according to timing of diagnosis. Aids, 26: 335-343.

Setegn, T., Takele, A., Gizaw, T., Nigatu, D., and Haile, D., 2015. Predictors of mortality among adult antiretroviral therapy users in southeastern Ethiopia: retrospective cohort study. AIDS Research and Treatment, 2015: 148769

Seyoum, D., Degryse, J.M., Kifle, Y.G., Taye, A., Tadesse, M., Birlie, B., Banbeta, A., Rosas-Aguirre, A., Duchateau, L., and Speybroeck, N., 2017. Risk factors for mortality among adult HIV/AIDS patients following antiretroviral therapy in Southwestern Ethiopia: an assessment through survival models. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14: 296.

Sieleunou, I., Souleymanou, M., Schönenberger, A.M., Menten, J., and Boelaert, M., 2009. Determinants of survival in AIDS patients on antiretroviral therapy in a rural centre in the Far‐North Province, Cameroon. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 14: 36-43.

Tadege, M., 2018. Time to death predictors of HIV/AIDS infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes, 11: 1-6.

Teklu, A.M., Nega, A., Mamuye, A.T., Sitotaw, Y., Kassa, D., Mesfin, G., Belayihun, B., Medhin, G. and Yirdaw, K., 2017. Factors associated with mortality of TB/HIV co-infected patients in Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences, 27: 29-38.

Tezera M., Demissew B.H., Fikire E., 2014. Survival Analysis of HIV Infected People on Antiretroviral Therapy at Mizan-Aman General Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 3: 1462 -1468.

Yirdaw, B.E. and Wencheko, E., 2015. Survival longevity of adult AIDS patients under ART : a case study at Felege-Hiwot Referral Hospital, Bahir-Dar, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development, 28: 2.

Young, S., Wheeler, A.C., McCoy, S.I., and Weiser, S.D., 2014. A review of the role of food insecurity in adherence to care and treatment among adult and pediatric populations living with HIV and AIDS. AIDS and Behavior, 18: 505-515.

OPEN access freely available online

Chiang Mai University Journal of Natural Sciences [ISSN 16851994]

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

https://cmuj.cmu.ac.th

Alemu Bekele Eticha

Department of Statistics, College of Natural and Computational Science, Mizan-Tepi University, Tepi, Ethiopia

Corresponding author: Alemu Bekele Eticha, E-mail: alemubekele1@gmail.com

Total Article Views

Editor:

Veerasak Punyapornwithaya,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: June 1, 2021;

Revised: August 14, 2021;

Accepted: August 17, 2021;