Symptom Experiences and Needs of Older Persons Living with Hemodialysis in Relation to Integrating Home Telehealth into Holistic End of Life Care: Phase I

Wanicha Pungchompoo* and Warawan UdomkhwamsukPublished Date : 2021-09-13

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/CMUJNS.2021.081

Journal Issues : Number 4, October-December 2021

Abstract The integration of home telehealth into holistic end of life care with nurse oversight for older persons living with hemodialysis is still limited in Thailand. This study explains the symptom experiences and health care needs related to integrating a home telehealth model into end of life care for older persons living with hemodialysis (OPLH). The paper represents the first phase of a mixed methods exploratory sequential study with dominant quantitative components, carried out over a six-month period. Purposive sampling was used to collect data from 100 OPLH. The instruments included the VOICES (View of Informal Carers Evaluation of Service-ESRD/Thai – patients’ version) questionnaire, the 9-item Thai Health Status Assessment questionnaire, and a demographic data form. The quantitative data were analysed using the statistical package SPSS version 17. Most of the participants had comorbid conditions (98%). The most common of these were hypertension (41.02%) followed by diabetes mellitus (23.25%). 25% had shortness of breath, and some had pain (31%), swelling (31%), anorexia some of the time (30%), and nausea and vomiting (15%). Moreover, participants also had symptoms of anxiety (23%), and moderate stress (10%). 8% had to be readmitted to hospital at least twice per month. Most participants had never received home care. The needs of the participants in relation to their holistic end of life care at home were reported in terms of: 1) knowledge of symptoms management at home; 2) activity and role management; 3) emotional management; and 4) spiritual support. The telehealth provision was mentioned by participants as an important part of their care, requiring VDO visiting, telephone counselling, and web-based education/ monitoring.

Keywords: ESRD, Older persons living with hemodialysis (OPLH), Home telehealth.

Funding: National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) and Chiang Mai University, Thailand.

Citation: Pungchompoo, W., and Udomkhwamsuk, W. 2021. Symptom experiences and needs of older persons living with hemodialysis in relation to integrating home telehealth into holistic end of life care: Phase I. CMU J. Nat. Sci. 20(4): e2021081.

INTRODUCTION

The proportion of people aged 65 and over has increased to 8.5% globally, and by 2050 this number is projected to increase to almost 17% (He, Goodkind, & Kowal, 2016). The number of older people in the Thai population has increased seven-fold in recent years, from approximately 1.5 million in 1960 to 10.7 million in 2015, representing 16% of the total population. In the year 2035 this number is forecast to have increased to over 20 million (Knodel et al., 2015).

The number of people aged 60 and over who have been living with chronic illness in Thailand over the past five years constitutes more than 3 million persons. This statistic shows an increase in chronic illness among the elderly population, with conditions such as cancer, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) becoming much more common (National Statistics Office, 2014).

The healthcare needs of older people are a focus for international healthcare research and policy worldwide (Hunt et al., 2014). The major emphasis of healthcare research should be focused on addressing the complex and diverse needs of older persons and their families, and helping older persons who are living with chronic conditions to achieve a good quality of life and experience a dignified death (Hirst et al., 2015). Therefore, understanding the symptoms, treatment and care experiences of older people living with chronic diseases, especially chronic kidney disease (CKD) or end-stage renal disease, is crucial for the provision of effective holistic home health care for OPLH at the end of life in Thailand.

Literature review

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) causes an increase in the numbers of older persons who need care for their daily living, as well as medical care for chronic health conditions. The prevalence of ESRD could rise sharply over the next few decades, and it is a long-term illness that involves a significantly increased risk of morbidity and mortality. ESRD can cause a physiological, psychological and social impact on wellbeing and quality of life, which can include fear of disease progression and risk of treatment complications (Han et al., 2019). ESRD is a chronic life-threatening condition and the disease is progressive; people can develop a variety of physical, psychological and social problems at any point during the illness (Zalai et al., 2012).

Renal replacement therapy (RRT) is an essential treatment technique, involving peritoneal dialysis (PD), hemodialysis (HD) and kidney transplantation (KT) (Kotanko et al., 2007). HD is used for those who need treatment for specific medical conditions and who might not able to receive PD (Pungchompoo, 2013). The number of persons living with ESRD who are receiving HD is expected to rise sharply in the next decade; an estimated 2 million people globally were receiving HD in 2010 (Liyanage et al., 2015), but this number is expected to have doubled by 2030 (Liyanage et al., 2015).

Annual reports on Thailand’s renal replacement therapy figures for the years 2016 to 2019 show that the number of persons living with ESRD and receiving HD in Thailand was estimated to be 114,262 in 2019 (Nephrology Society of Thailand, 2020). The incidence of new cases of Thai people living with ESRD and receiving HD was 39,398 during the period from 2017 to 2019. Diabetic nephropathy (44%) and hypertensive nephropathy (38.9%) were the most common causes of CKD in Thailand, and the patients receiving HD and PD were aged around 45 to 64 years (41%), 65 to 74 years (24%) and 75 years and over (20%).

The numbers of OPLH are rising steadily, with an annual increase in older persons living with hemodialysis. During hemodialysis cycles people living with ESRD fluctuate in terms of their cognitive and physical wellbeing, as well as in their emotional state (Jones et al., 2017). As the number of persons living with end-stage renal disease increases, understanding and managing symptoms effectively, and thereby improving quality of life for people living with ESRD, will become increasingly important. Older persons living with ESRD also employ a range of internal resources to maintain a meaningful role in their life, where coping with fear, anger, frustration and increased mortality risk have to be managed (Clarkson and Robinson, 2010) alongside providing knowledge about the disease, vascular access management and participation in treatment, which are all significant to both patients and partners. They have concerns about illness progression, and relationships with their social networks and healthcare professionals form a significant and important part of daily life for both parties (Gullick et al., 2016; Cowan et al., 2015). When an individual has a disease, it is not only the individual who is affected; there are also many impacts on the person’s family. Close relatives can be exposed to stress and a caregiver burden as a result of the daily care interventions or challenges that a serious illness can require (Kang and Nolan, 2011). These burdens impact on a person’s daily life, and affect family members who provide most of the support and care for persons living with ESRD. Carers can experience depression, reduced sleep quality and quality of life (Gerogianni and Babatsikou, 2014). Informal caregivers reported a high level of burden in caring (mean 40.15, SD= 10.46) with 80.9% identifying the level as severe (Hoang et al., 2019).

ESRD is typically viewed as the static end point of chronic renal failure. However, the new holistic paradigm suggests that patients’ experience of ESRD continues to evolve from the time of diagnosis until death. Murtagh et al. (2011) conducted a longitudinal study of the trajectory of stage 5 chronic kidney disease in terms of patient symptoms and concerns in the last year of life, and found that the trajectory of ESRD patients showed a sharp increase in symptoms of distress and health-related concerns during the final two months before death. The demand for care at the end of life is increasing because of the growing number of terminally ill persons seeking quality care. At present Thailand does not have palliative and hospice units in every hospital, since the national healthcare policy is focused on curative intervention within the area of acute and chronic illnesses (Thiamwong & Pungchompoo, 2018). Few hospitals provide a home-based palliative care service, and bereavement services are not formally provided for Thai families (Tipseankhum et al. 2016). Furthermore, the negative impacts of hemodialysis are shown in increasing morbidity and mortality rates, reduced quality of life, and a gap between health needs and inadequate symptom managements at home (Pungchompoo, 2014).

In this situation, palliative care will be able to improve or maintain quality of life for patients and their families, especially those who are facing life-threatening illness, by providing pain and symptom relief, as well as spiritual and psychosocial support from diagnosis to the end of life and bereavement. The concept of palliative care may be applied to renal disease by using an agreed management plan to optimise the quality of life and relieve suffering from pain and other symptoms (WHO, 2004). The process of renal palliative care may be incorporated with the geriatric principles and involve a multidisciplinary team to offer a holistic approach to care (Swidler, 2009). Murtagh

et al. (2007) suggested that ESRD patients should receive a palliative care approach at the early stage of their illness in order to be prepare for moving to the advanced stage. Active medical management of renal complications, such as treatment of fluid/electrolyte disorders, renal anemia, fluid overload and mineral bone disease, is needed together with the management of geriatric syndromes (pain, depression, fatigue, constipation) to maintain function and QOL, reduce hospitalisation, and enable patients and carers to live with dignity when the end of life approaches.

End of life care is a challenging situation confront healthcare teams in Thailand, especially since the process of dying is unpredictable and needs complex care. This complexity is in part due to the fact that end of life care is an essential aspect of providing care to older people who are less likely to have access to specialist palliative care and more likely to have poor symptom management at the end of their lives ( Hunt et al., 2014). The physical, psychological and spiritual needs of patients change during the last year of life, often increasing in severity in the last few months before death (Pungchompoo et al., 2016). These changes are not addressed effectively by the health services that are available in Thailand. Therefore, knowledge is required about symptom experiences and needs to prepare for holistic end of life care. This may be done by integrating telehealth for this population.

Telehealth, integrating holistic and interprofessional management, is a new model of care within chronic disease management. Telehealth and inter-professional care may be successfully implemented with a meaningful engagement with the care system. Telehealth by an interprofessional team has been shown to be a feasible care delivery strategy for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Ishani et al., 2016). Emerging evidence supports the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of using home telehealth monitoring to promote health and chronic disease management. One study has demonstrated improved health outcomes and cost-effectiveness in high-risk people with ESRD (Berman et al., 2011), using remote technology (RT) for home health monitoring with support from remote care nurses (RCNs). The success of home telehealth relies heavily on patient adherence to a prescribed programme, and home telehealth monitoring with RCN support brings hope and an improved quality of life. Moreover, home telehealth self-monitoring with RCN support is effective in empowering patients to take a more active role in their health care, indirectly improving quality of life for people living with chronic illness (Suwanrada et al., 2016).

The best reason for developing home telehealth services is that many patients with advanced conditions can remain at home and in their own communities, but when they experience problems they may feel unsure about who they can contact and how (Johnston et al., 2015). The use of telehealth services can help to empower individuals in terms of their experience of life-limiting illness, and improve the experience of their carers, by facilitating the provision of real-time communication between patients and healthcare providers (Johnston et al., 2015). It can also be used to complement current transitions within health care from acute services, based on patient need (Roberts et al., 2007).

The value of home telehealth self-monitoring with nurse oversight has been demonstrated, but there is a limited amount of objective documentation of patients’ experiences of and needs within such a model in Thailand. Therefore, this first phase of a wider mixed methods study aims to describe and explore the experiences and needs related to integrating home telehealth into holistic end of life care with nurse oversight for OPLH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This descriptive study is the first phase in a wider mixed methods design for a multistage research project (Creswell et al., 2011). A mix of quantitative and qualitative methods was used to employ a prospective approach to collecting data, in order to describe the symptom experiences and healthcare needs of OPLH.

Setting/Subjects

100 older people aged 60 or over who had been living with hemodialysis were recruited as participants in the quantitative part of the study. Participants were recruited from two renal units from two hospitals in Chiang Mai province, Thailand during a period between 1 January and 30 June 2017. Previously, the researcher had sent information letters and copies of the study protocol to the administrators of the relevant medical units to ask them for permission to collect data. The medical units also had a register of older people who had been diagnosed with ESRD and who were receiving hemodialysis. All the participants met the inclusion criteria and were willing and able to participate in the study, as well as being capable of providing informed consent.

Inclusion criteria

People who were eligible to participate in the study if they were aged 60 years or over and if they: 1) were being managed for HD, and 2) had diagnosed with ESRD stage 5 by a nephrologist. Eligible participants gave informed consent to participate in the study. Those who were hospitalised with acute illnesses, who had psychological or cognitive disorders, or who had physical limitations for self-care were excluded.

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Faculty of Nursing and the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Thailand, IRB No. 096-2016 (date of approval November 30, 2016; date of expiry November 29, 2017), before the process of data collection began.

Data collection

Survey data collection was employed. A nonprobability sampling method was used to obtain the sample (Creswell et al., 2011). 100 OPLH were surveyed over a period of 6 months. Purposive sampling was used to collect data from the participants. The instruments included the VOICES (View of Informal Carers Evaluation of Service-ESRD/Thai – patients’ version) questionnaire, and the 9-item Thai Health Status Assessment questionnaire.

Instruments

Demographic data were collected at baseline. Participants were asked to provide information about their age, gender, marital status, educational level, occupation, and household income by completing the demographic data form.

The VOICES (View of Informal Carers Evaluation of Service-ESRD/Thai – patients’ version) questionnaire has been used previously to evaluate the experiences and healthcare needs of patients with ESRD in the last year of life. This version was modified from the adapted VOICES-Thai version (Pungchompoo, 2013) by the researcher, adapting relevant questions from different versions of the VOICES questionnaire (COPD, stroke, cancer, and heart failure) and the Views of Informal Carers – Evaluation of Services Short Form (VOICES-SF) (Hunt and Addington-Hall, 2011). The VOICES questionnaire has been successfully applied and validated in more than thirteen surveys and over 4,000 respondents, assessing the quality of care given to patients dying from many different diseases (e.g. cancer, stroke, COPD, chronic heart failure and dying in a hospice) (Hunt and Addington-Hall, 2011). The adapted VOICES-Thai version (Pungchompoo, 2013) consists of ten sections and 69 items. The total time to interview each participant was estimated to be between 30 and 45 minutes. Items were predominantly fixed-response, with the opportunity for further comments. The scores in each section were different.

The 9-THAI has been used to evaluate quality of life and the health status of patients receiving continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) (Cheawchanwattana et al., 2006). The 9-Thai is separated into 2 two scales, yielding physical and mental health scores (PHS, MHS). The standardised T-scores of PHS and MHS are stratified by gender and age-group and based on the average values for the generally healthy Thai population. The 9-THAI is composed of 7 domains and 2 global health ratings, and encourages subjects to rate their experiences with health conditions during the past month (Saisunantararom et al., 2015). Response choices for the 7 domains are interpreted according to the perceived severity of the problems on a 5-point scale, where 1 = “very severe”, 2 = “severe”, 3 = “moderate”, 4 = “mild”, and 5 = “not at all”. The first global question is used to compare participants’ health at the present time with their health during the year before. The second question compares their health with the health of others of a similar age, gender, social/economic status, type of employment and lifestyle. Response choices for the 2 global questions range between 1 = “much worse”, to 2 = “a little bit worse”, 3 = “the same as”, 4 = “a little bit better”, and finally to 5 = “much better”. The calculated score values range between 20 to 80 (±3SDs); if the PHS or MHS of patients are above 20, then scores are interpreted as equal to the generally healthy Thai population. Higher calculated scores reflect better health than the general population.

The 9-Thai is a valid and reliable quality of life (QOL) measure in Thai renal replacement therapy patients. Its validity has been shown in terms of convergent and divergent validity using the SF-36 as a concurrent measure. Its concurrent validity has also been assessed using clinical variables. The reliability of the 9-Thai according to test-retesting was satisfactory, as the inter-class correlation coefficients were at 0.79 (PHS) and 0.78 (MHS).

Data analysis

The quantitative data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (version 17). Descriptive statistics (means, rates and percentages) were used to describe the demographic data, and the needs and experiences of the participants in the sample. The questionnaire data were analysed and presented as percentages.

Table 1. Socio-demographic data of the participants (n = 100)

|

|

Number (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

Male Female |

51 49 |

51.00 49.00 |

|

Age (mean = 68.32, S.D. = 7.61) |

|

|

|

60–69 70–79 80–89 >90 |

43 38 18 1 |

43.00 38.00 18.00 1.00 |

|

Marital status |

|

|

|

Single Married Divorced Widowed Separated |

4 62 3 29 2 |

4.00 62.00 3.00 29.00 2.00 |

|

People living together |

|

|

|

Husband/wife/child Relatives/siblings Alone Nursing home |

89 9 1 1 |

89.00 9.00 1.00 1.00 |

|

Regular contact person |

|

|

|

Husband/wife Child Relatives/siblings Friend Physician CP Foundation None |

35 50 8 2 3 1 1 |

35.00 50.00 8.00 2.00 3.00 1.00 1.00 |

|

Religion |

|

|

|

Buddhist Christian |

99 1 |

99.00 1.00 |

|

Education level |

|

|

|

Unlettered/can’t read or write Unlettered/able to read and write Primary education Secondary education Higher Vocational Certification Bachelor’s degree Postgraduate |

1 0 66 18 3 9 3 |

1.00 0.00 66.00 18.00 3.00 9.00 3.00 |

|

Current occupation |

|

|

|

Unemployed Housewife Trading/personal business Employee Retired government employee Lawyer State enterprise |

80 1 6 2 9 1 1 |

80.00 1.00 6.00 2.00 9.00 1.00 1.00 |

|

Family income per month (baht) |

|

|

|

<5,000 5,001-10,000 10,001-15,000 15,001-20,000 20,001-25,000 25,001-30,000 >30,001 None Source of help with income sufficiency |

33 16 14 7 3 8 17 2 |

33.00 16.00 14.00 7.00 3.00 8.00 17.00 2.00 |

|

Husband/wife Child Relatives/siblings Other |

3 87 4 6 |

3.00 87.00 4.00 6.00 |

|

Income sufficiency |

|

|

|

Enough left to keep Enough but none left over Not enough, no debt Not enough, with debts |

28 39 22 11 |

28.00 39.00 22.00 11.00 |

|

Payment of medical expenses |

|

|

|

Self payment Free treatment Dismissal from agency Social Security Scheme Buddharaksa Foundation Retired government employee Queen’s Foundation |

6 14 71 6 1 1 1 |

6.00 14.00 71.00 6.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 |

RESULTS

Part 1: Demographic characteristics of the participants – frequencies (%)

Most of the participants were aged between 60 and 69 years (43%), with an average age of 68.32 years (SD = 7.61). Most of them were male (51%), and most were married (62%). 89% lived with their husband, wife and children. The regular contacts of OPLH were mostly their children (50%), followed by their husband or wife (35%). Most were Buddhist (99%). In terms of their education level, most were educated to primary level (66%), followed by 18% who had studied at secondary level. Most of the older persons with chronic renal failure were unemployed (80%), followed by trade/personal business (6%). The majority had a monthly family income less than or equal to 5,000 baht (33%), followed by those with an income greater than or equal to 30,000 baht (17%). If the OPLH, the majority received assistance from their children (87%), and most had enough money to live on but none left over (39%), followed by those with some left over (28%).

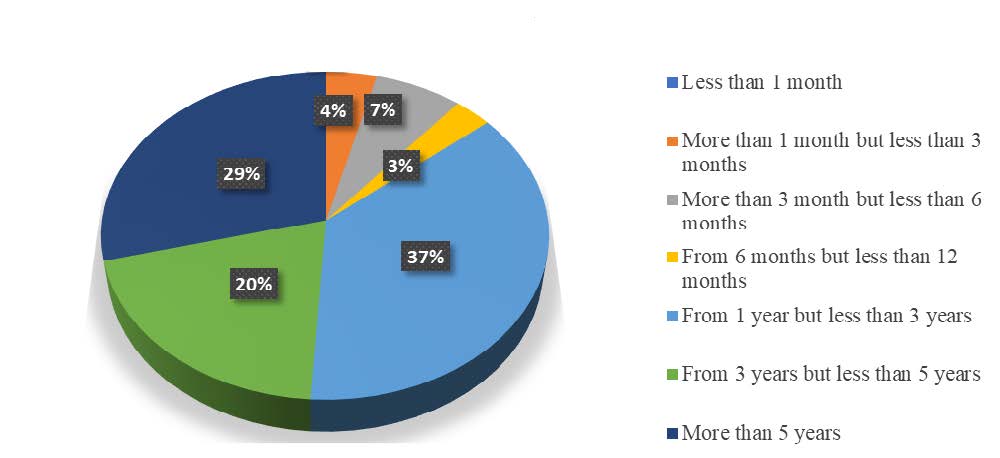

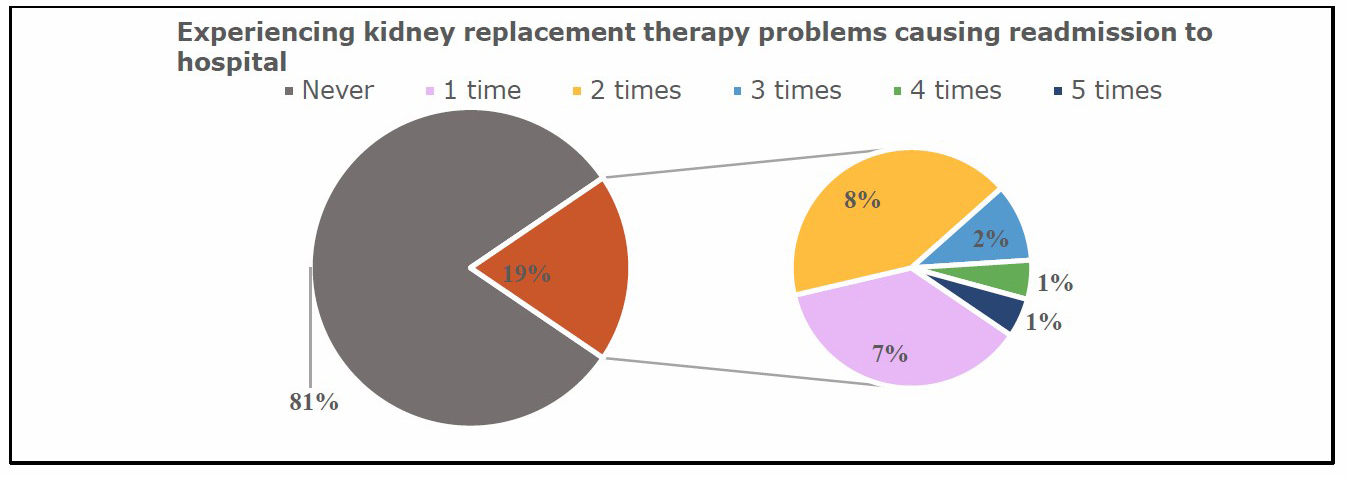

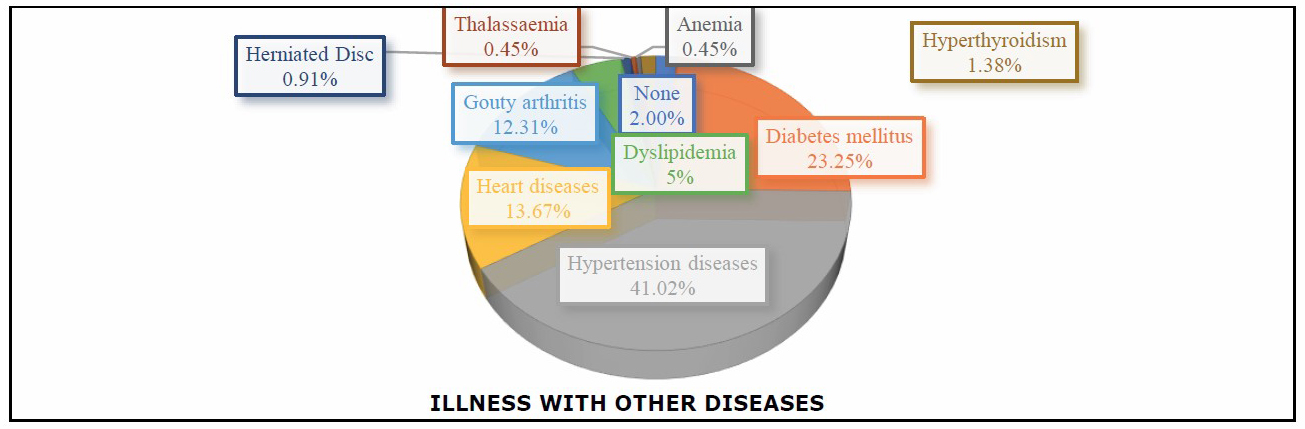

Figures 1, 2, and 3 show that most of the OPLH for between 1 and 3 years (37%). They mostly received advice on self-management of their kidney replacement therapy from health team staff such as doctors and nurses (54.64%), followed by family members such as their husband, wife, children, relatives or siblings (20.22%). The majority (81.00%) had never experienced kidney replacement therapy problems causing a readmission to hospital. However, 19% had experienced problems and had been readmitted to hospital; of these, most had experienced this twice (8.00%), and others only once (7.00%). 98.00% had other illnesses, most commonly hypertension (41.02%) followed by diabetes mellitus (23.25%).

Figure 1. The duration of renal replacement therapy.

Figure 2. Experiencing kidney replacement therapy problems causing readmission to hospital.

Figure 3. Illness with other diseases.

From the assessment of the general health status of OPLH shown in Table 2, it may be seen that the mean score was 45.56, suggesting that the physical quality of life for OPLH is comparable to normal Thai people in good health. The mean score of 49.78 for general quality of life suggests that the quality of life of OPLH is also comparable to that of normal Thai people in good health.

Table 2. The general health status of OPLH (n = 97).

|

Average Score |

Evaluation results |

|

45.56 |

The physical quality of life is the same as that of normal Thai people in good health. |

|

49.78 |

The quality of life is equal to that of normal Thai people in good health. |

Part 2: Symptom experiences

Physical symptoms

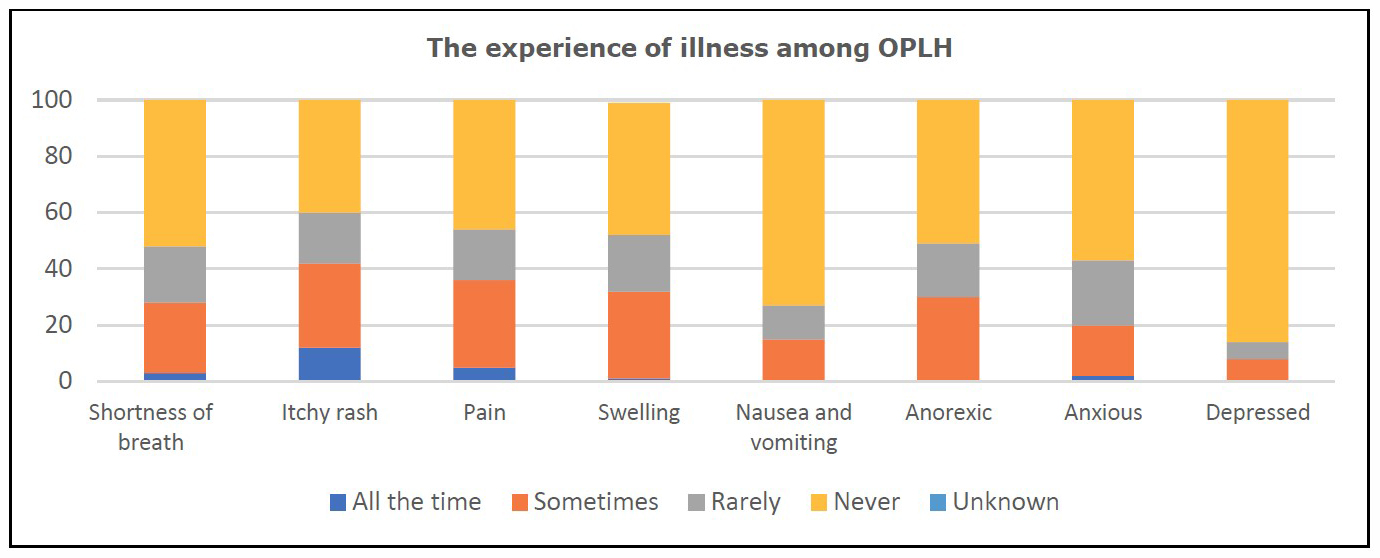

Figure 4 shows that among OPLH, 25% had sometimes experienced shortness of breath, but 52% had never experienced it. 30% had experienced a rash, but 40 % had never experienced this. Some had pain (31%), swelling (31%) or nausea and vomiting (15%). 30% had experienced anorexia, but 51% had never done so. 23% had experienced symptoms of anxiety, but 57% had never suffered from this. Finally, 8% had sometimes experienced symptoms of depression, but 86% had never had these symptoms.

Figure 4. The experience of illness among OPLH (n = 100).

Psychological symptoms

From Table 3, it may be seen that the stress levels of OPLH were low (90.00%) or moderate (10.00%).

Table 3. The stress levels of OPLH (n = 100).

|

Stress level |

Low (%) |

Moderate (%) |

|

Number of OPLH |

90 (90.00) |

10 (10.00) |

Health care needs and utilisation

Health services provision

Table 4 shows that most of the OPLH had received help or care from family and friends with taking medication (68%), household workload (61%), night care (55%) and personal care (41%). Most had never received home care, support or care from health personnel.

Table 4. Receiving assistance or care from family, friends or home care health workers (n = 100).

|

Helping or care at home |

Personal care |

Housework |

Night care |

Taking medicine |

||||

|

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

|

|

Family, friend |

41 |

59 |

61 |

39 |

55 |

45 |

68 |

32 |

|

|

(41.00 ) |

(59.00) |

(61.00) |

(39.00) |

(55.00) |

(45.00) |

(68.00) |

(32.00) |

|

Health personnel |

0 |

100 |

0 |

100 |

1 |

99 |

2 |

98 |

|

|

(0.00) |

(100.00) |

(0.00) |

(100.00) |

(1.00) |

(99.00) |

(2.00) |

(98.00) |

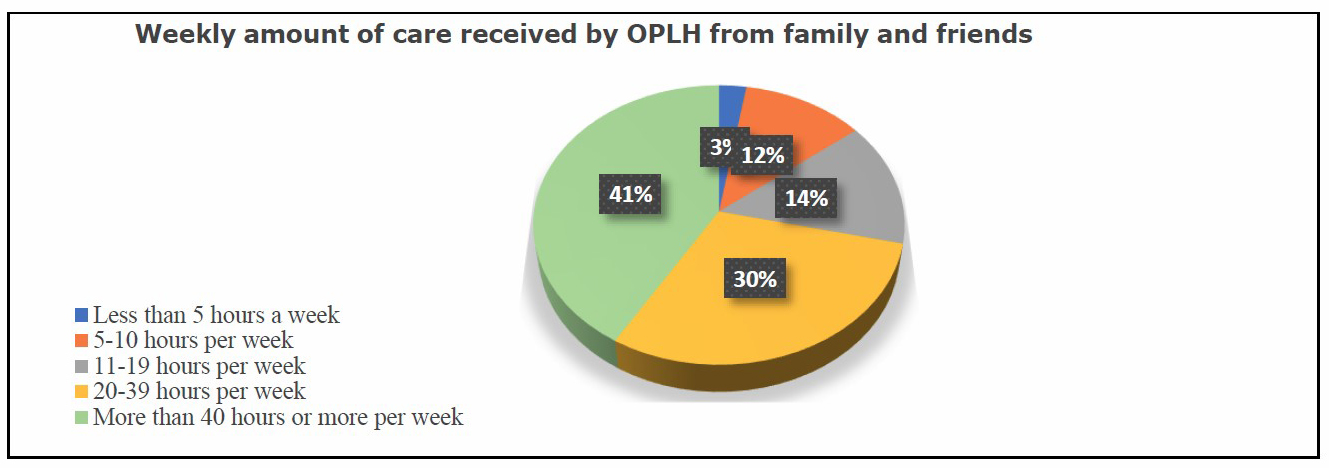

Figure 5 shows the weekly amount of care received by OPLH from family and friends. Most received more than 40 hours per week (40.79%), followed by 20–39 hours per week (30.36%). Only 3% received help or care at home for less than 5 hours a week.

Figure 5. Weekly amount of care received by OPLH from family and friends (n = 76)

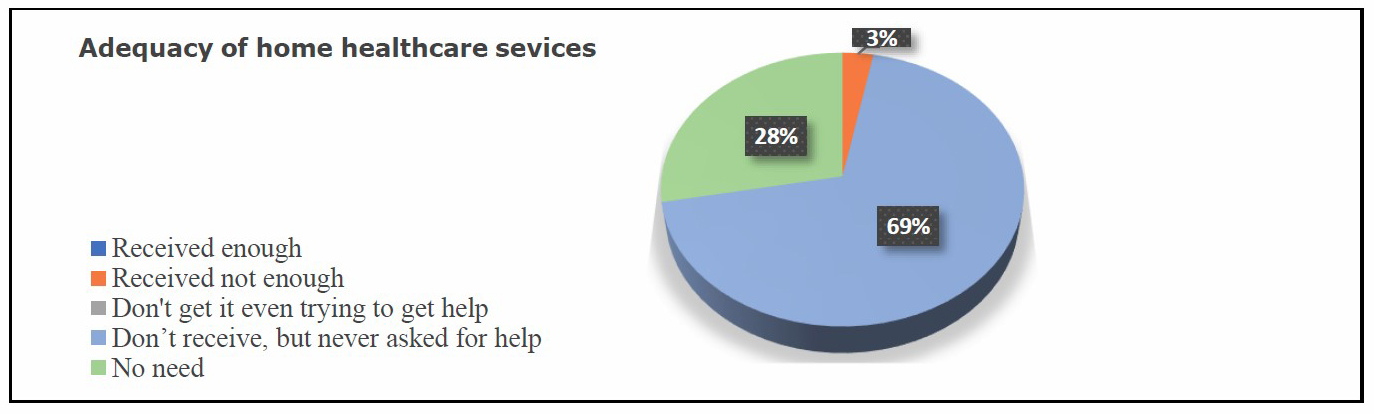

Figure 6 shows that most (69%) of the OPLH did not receive assistance or healthcare services from hospital staff in terms of their care at home, although they had never asked for any assistance. 28% said they had no need for any assistance. The 3% of the OPLH who had received assistance from health services personnel felt that this was not enough.

Figure 6. Adequacy of home healthcare services provided by hospital staff for OPLH (n = 100).

Home visiting

Table 5 shows that 10% of our sample of OPLH had received home visits from provincial nursing staff, district nurses or community nurses. Of these, 20% had been visited by a nurse from provincial hospital, 20% by a district nurse and 60% by a community nurse. The most common type of home visit was by community nurses at 60%.

Table 5. Home visits by provincial, district and community nurses (n = 100).

|

Home visits by provincial, district and community nurses to OPLH |

Amount |

Percentage (%) |

|

1. Getting help at home with health problems as a result of renal failure |

|

|

|

No |

90 |

90 |

|

Yes |

10 |

10 |

|

2. Types of home nursing staff |

|

|

|

Nurse from provincial hospital |

2 |

20.00 |

|

Nurse from district hospital |

2 |

20.00 |

|

Community nurse |

6 |

60.00 |

Spiritual need

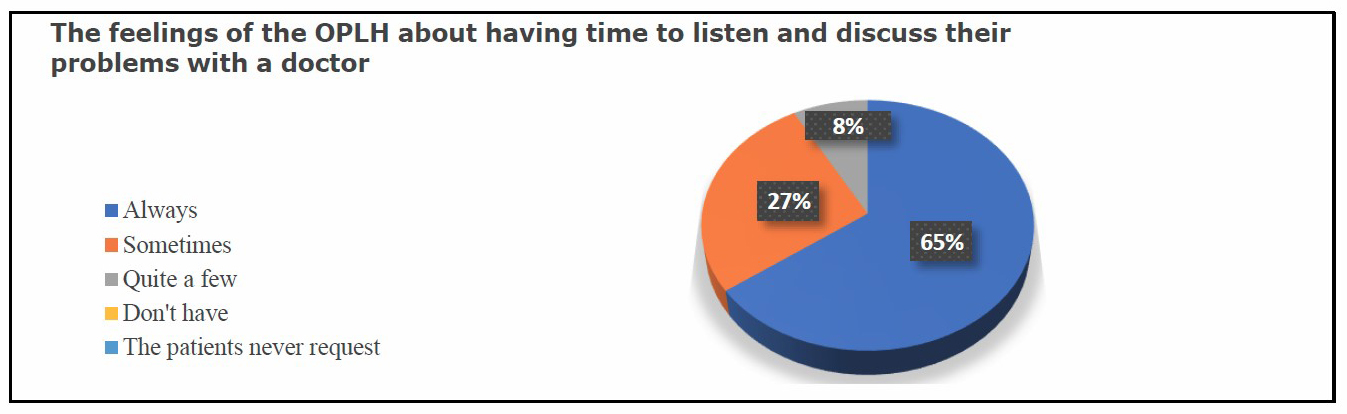

Figure 7 shows that 65% of the OPLH in our sample felt they always had time to discuss their problems with their doctors. 27% felt their doctors sometimes had time to listen to and discuss their problems.

Figure 7. The feelings of OPLH about whether they had time to discuss their problems with a doctor (n = 100).

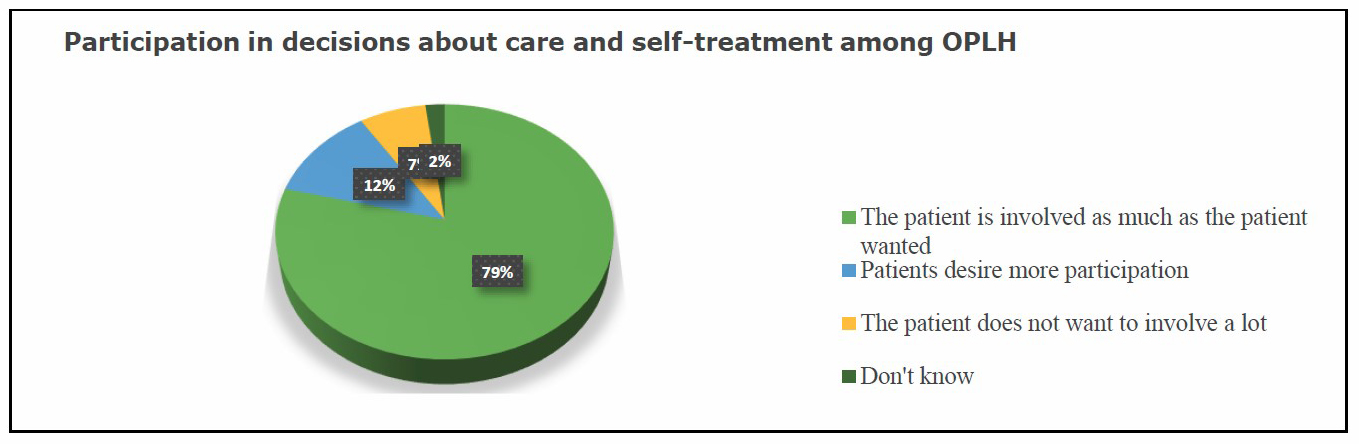

Figure 8 shows that 79% of the OPLH felt they had as much involvement as they wanted in decisions about their care and self-treatment. However, 12% wanted to be more involved in these decisions.

Figure 8. Participation in decisions about care and self-treatment among OPLH (n = 100)

DISCUSSION

This study fills a research gap and generates new knowledge by developing our understanding of and providing evidence about the experiences and healthcare needs of older people with end-stage renal disease who are living with hemodialysis, especially in terms of integrating a holistic home telehealth framework.

Overall quality of care

Our findings show that for the most part, the quality of life of the participants was comparable with the quality of life reported by Thai people in good health. This accords with research by Miyashita et al. (2015) indicating that family members were satisfied with end of life care in all places of death in Japan. However, Andersson et al. (2017) indicated that patients in residential care homes (RCHs) in Sweden received inadequate pain relief and experienced breathlessness during the last days of their life. The quality of care during the last three months and the last three days of life among those who died in RCHs was high, based on a positive picture of personal and nursing care and good communication including respectful interactions, provision of information about imminent death and shared decision making (Andersson et al., 2017). However, inadequate management of symptom relief during the last three days of life was also found to be a risk indicator for poor quality of end of life (EOL) care in old age. The majority of the families’ burdens, differences in disease trajectories and individual needs for specific palliative care, social services and information support for patients and families may also affect satisfaction with the quality of the EOL care received.

The value of home telehealth with nurse oversight does not only focus on the quality of life provided; evidence also suggests that the feasibility and cost effectiveness of providing home telehealth monitoring can promote health and chronic disease management (Minatodani et al., 2013). One randomised controlled trial demonstrated that health outcomes and cost effectiveness in high-risk patients with ESRD improved with the use of remote technology for home telehealth monitoring and remote care nurse support (Berman et al., 2011). According to this evidence, improving holistic care, providing emotional support and good communication of information at the end of life between patients, families and care professionals are all still important prerequisites for improving the quality of EOL care (Addington-Hall and O’Callaghan, 2009; Andersson et al., 2017). Home telehealth with self-monitoring and nurse support, may therefore prove effective in empowering OLPH to take a more effective role in their healthcare, indirectly improving their quality of life.

Symptom experiences

Physical symptoms

Among OLPH, the intensity of symptoms increases and there can be a rapid decline in their physical health. A picture emerged of a heavy symptom burden which was extremely distressing for some, with symptoms such as pain, edema, shortness of breath, anorexia and nausea and vomiting appearing to be common and happening all the time. A systematic review reported the symptoms that persons with ESRD experience, listing pain, itching and restless legs syndrome, and indicating that these patients have a high prevalence of symptoms and a considerable symptom burden (Murtagh et al., 2007). During the last three months of life respondents with non-cancer diagnoses were found to experience pain (79.4%), while breathlessness (73.9%) was commonly found whether in hospital or at home (Addington-Hall and O'Callaghan 2009).

Similarly, Andersson et al. (2017) revealed that about half (46.5%) of their older participants had pain and 55.9% had breathlessness during the last three months of life, and in particular the proportion of older persons who experienced breathlessness while dying was high in RCHs. The symptoms experienced by persons with Stage 5 CKD were edema (96%), pain (90%), immobility (60%), breathlessness (50%), pruritus (47%), lethargy and insomnia (53%) and depression (37%) (Noble et al., 2010). In the month before death, common symptoms of elderly persons with stage 5 CKD were lack of energy (86%), pruritus (84%), drowsiness (82%), dyspnea (80%) and pain (73%) (Murtagh et al. 2011). In addition, the family members of OLPH reported that breathlessness caused the most suffering and created the greatest sense of difficulty for them during the last three months before death (Pungchompoo et al., 2016). Although pain has not been considered as the most problematic issue for renal patients (Murtagh et al. 2006), it is often prevalent and a major problem for ESRD persons undergoing hemodialysis at the end of life (Årestedt et al., 2018).

Psychological symptoms

The participants reported symptoms of anxiety, depression and moderate stress. Pain caused the most suffering to participants at all times, while poor appetite, worry, low mood, breathlessness and edema sometimes occurred. Similar to research on patients receiving chronic hemodialysis, depressive symptoms and pain are independently associated with dialysis nonadherence and health resource utilisation, whereas depressive symptoms are also independently associated with mortality (Weisbord et al., 2014).

Psychological symptoms including worry and low mood were found to be a crucial issue of concern for this group. Similar to earlier studies, worry impacted on OLPH such that they were unable to control their emotions, especially when they suffered severe breathlessness during the last months of life; patients felt panic, and a fear of dying surfaced (Pungchompoo et al., 2016). Nobel et al. (2010) observed that some ESRD patients suffered low mood after overhearing, from the doctor, that nothing more could be done for them. In comparison, Davison (2010) found that ESRD patients with depression may not always clearly show the impact of their symptoms, but this could have been an important influence when considering the ways in which some ESRD patients respond to treatment.

Based on this evidence from previous studies and the findings from this research, psychological symptoms among patients, such as worry and low mood, accompany the experience of patients living with chronic conditions, and ineffective control of physical symptoms including breathlessness and pain appear to contribute to this. In Thailand, the symptoms of many patients are currently not well managed because of limitations in the availability of specific symptom management at home, such as oxygen support and pain control (Pungchompoo et al., 2016). According to Andersson et al. (2017), to achieve the effective management of symptoms for older people living with chronic conditions during the last three months of life in Thailand, clinical care pathways for symptom relief should be improved to provide better care and relieve their suffering.

Spiritual distress

Because of the importance of spiritual beliefs in Thai culture, at the end of patients’ lives their spiritual beliefs were shown to be an important factor, especially when patients were faced with uncertainty regarding symptom burden, the deterioration of their health condition and their medical treatment. However, the results of this research suggest that most of the OLPH felt that their doctors had the time to listen to them and discuss their problems. Thais rarely display strong negative emotions, with bouts of anger, tantrums, and public crying being rather unusual. Therefore, religion has a profound influence on end of life care in Thailand. In order to provide a holistic end-of-life approach that meets the spiritual needs of Thai people, understanding, respecting and planning interventions to facilitate patients’ spiritual and religious beliefs and practices are recommended.

Telehealth may be the best strategy to reduce symptom suffering, improve health outcomes, provide timely and convenient care for OPLH regardless of their location, and offer high value with the potential to decrease overall health system costs (Ishani et al., 2016). Rifkin and colleague (2013) conducted an RCT study and found that home monitoring could improve clinical outcomes in CKD patients. It could also decrease rates of hospitalisation, readmission and emergency department visits, and it could be effectively implemented with moderate to severe CKD patients. In the Thai context, the characteristics of OPLH may be different from those in other countries. Most of these patients live in rural areas, they are poor, and they have a generally low level of education. These factors may lead to ineffective management of their clinical symptoms, and complications when they have to manage their hemodialysis at home. During the advanced stage of ESRD symptom experiences (physical, psychological and spiritual aspects) should be closed monitored by nurses and healthcare teams; active home monitoring and comprehensive interprofessional care via a home telehealth programme could control hypertension, prevent clinical deterioration and perhaps help to predict disease progression (O’Naill et al., 2014: Ishani et al., 2016). Integrating holistic home telehealth at the end of life approach may also offer other benefits, particularly among subgroups who need specific care (e.g. OPLH).

Healthcare needs and integrating holistic home telehealth

The findings show that most of the participants had received help or care from their families and friends with taking medication, household workload, night care, and personal care. They had never received home care, support or care from health personnel. Healthcare professionals need to define the roles that various members of multidisciplinary teams will play in the provision of EOL care, such as symptom management and psychological and spiritual support (Davison, 2010). Many countries have reported shortages of providers who are essential for ESRD care, mainly because there are not enough nephrologists, interventional radiologists for hemodialysis access, surgeons for peritoneal dialysis access, and nurses (Bello et al. 2019). Accordingly, a lack of risk-bearing partners outside of dialysis facilities and nephrologists may limit patients’ ability to effect their care more broadly (Marrufo et al., 2020). Focusing on treatment-related tasks and symptom management requires more caregiving time, and this is where renal nurses could provide information, education and support to caregivers and OLPH regarding vascular access care, knowledge about medication, how to maintain dietary and fluid restrictions, and monitoring for signs and symptoms of HD complications, fluid overload etc.

Education is also needed on how to handle complications, so that caregivers can feel more confident to carry out these actions. It has been recommended that education should target individual needs and be delivered in multiple forms (i.e. dialysis classes, tours of dialysis facilities, information leaflets, and personal consultations). Dialysis facilities may be highly feasible sites to meet individual-level social needs using existing staff and resources, given the high frequency of patient visits and embedded multidisciplinary care teams (Tummalapali and Ibrahim, 2020). Successful management of CKD requires ESRD patients to understand the disease presence and process. Knowledge about the disease and participation in treatment are significant to both ESRD patients and their partners. There are considerations about illness progression, and an education program based on a theory and concept of self-management and health promotion principles is recommended to improve health-related quality of life for people living with CKD (Fung et al., 2017; Pungchompoo et al., 2019). Relationships with people in their social networks and with healthcare professionals are a significant and important part of daily life for both parties (Frandsen et al., 2020). An adequate patient understanding of CKD has therefore become a central focus of management to prevent CKD progression; there is a clear association between poor health literacy and adverse outcomes, but greater ESRD patient preparedness is associated with an improvement in health outcomes. Unfortunately, the availability of ESRD patient education materials related to CKD is limited.

With limited time available during an office visit, methods utilizing web-based education are important in expanding and reinforcing the education that is received during a medical appointment. To maintain a continual source of patient education for persons with CKD and their caregivers, web-based or e-kidney clinic applications need to be developed.

Home visits were identified by participants as the main service that should be provided regularly in order to monitor and control patients’ symptoms. Health service provision that includes a referral system, early investigation by a specialist, health education, support at the end of life and care with dignity (effective symptom and pain management, oxygen, psychological and spiritual support at home) are all required to best suit individual needs (Pungchompoo et al., 2016). Clinical staff should be required to undertake specific training on EOL care (Beccaro et al., 2010; Noble et al., 2010). Similarly, emotional, spiritual, and social support should be integrated with medical support (Addington-Hall and O'Callaghan, 2009).

Telehealth has been confirmed to provide positive treatment outcomes and facilitate behavioural changes when self-assessment procedures are used as therapeutic interventions (Wu, 2012). Telehealth can facilitate a timely medical response if the enrolled patients have an emergent condition (Hsu et al, 2010). It also reduced hospital readmission rates from 8.19% to 3.17%, the hospital visit rate decreased from 2.95% to 2.90%, and the medication nonadherence rate reduced from 38.20% to 9.30%. A home telehealth programme may provide in-home education, facilitate visits using VDO, help to manage clinical complications (such as pain, breathlessness, edema and anxiety), and identify and address acute conditions. Such a model could be created to monitor medical adherence and encourage patients to perform effective self-management behaviours in terms of their fluid intake, nutrition control, exercise, and emotional education and support.

The research evidence shows that successful home telehealth with nurse support promotes health behavioural change and results in better outcomes and the early identification of clinical complications, as well as promoting illness self-management skills. In addition, telehealth has been suggested to improve the quality of the relationship between patients and healthcare providers (e.g. nurses, physicians), which could impact on treatment adherence and might enhance self-management and better outcomes (Katon et al., 2010). The high levels of satisfaction with healthcare increase patients’ motivation and treatment adherence (Tousignant et al., 2011). Holistic home telehealth emphasising technology and health outcomes should rely on the partnership between patients and their healthcare providers. Integrating home telehealth is therefore strongly recommended to improve the quality of patients’ lives (Minatodani et al., 2013).

Implications for clinical practice

Further research is needed regarding the support and activities of caregivers and persons with hemodialysis. Telehealth can offer many benefits by applying the concept of palliative care for OPLH. However, in practice it may encounter various barriers. First, the patients’ willingness to participate in telehealth services must be evaluated early. Second, telehealth must produce more evidence for its effectiveness in order to negotiate with policy makers who will need to continue to invest in the required technology. Home visits are still necessary to provide quality of end-of-life care, but a user-friendly electronic device at home is also needed. In this regard, existing equipment and technology innovations are both required.

In terms of the generalisability of our results, there is a need to conduct further research that develops and examines the effectiveness of support interventions or an integrated home telehealth model, in order to determine whether a fully integrated holistic home telehealth model could alter OPLH outcomes.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study have generated significant new knowledge about the symptoms, experiences and healthcare needs of older persons living with hemodialysis in Thailand. Patients suffer with their physical, psychological and spiritual conditions at home. Therefore, a new technological approach to integrate holistic end of life care for older persons undergoing hemodialysis is needed to provide for them and their caregivers. Additionally, the development of a nurse-led online visiting programme will be useful in helping nurses to improve the quality of end-of-life care by effectively providing assessment, monitoring and counselling services. The integration of holistic home telehealth may be an effective new strategy to improve patients’ physical outcomes, maintain their quality of life and reduce their emotional and spiritual suffering. Furthermore, telehealth enables older people with chronic illnesses to live independently, and helps institutionalised older people to receive acute care more efficiently without the need for increased manpower in healthcare organisations (Hsu et al., 2010).

In short, telehealth offers many benefits that may help with the long-term care of our aging population. Implementing home telehealth might help to meet the needs of the elderly in the aging population, and could reduce rates of readmission to hospital (Hsu et al., 2010).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) and Chiang Mai University, Thailand. The authors whould like to give special thanks to their participants who graciously gave their time to take part in this study.

REFERENCES

Addington-Hall, J.M. and O'Callaghan, A.C., 2009. A comparison of the quality of care provided to cancer patients in the UK in the last three months of life in in-patient hospices compared with hospitals, from the perspective of bereaved relatives: Results from a survey using the VOICES questionnaire. Palliative Medicine. 23: 190-7.

Andersson, S.E., Lindqvist, O., CJ F. et al., 2017. End of life care in residential care homes: A retrospective study of the perspectives of family members using the VOICES questionnaire. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 31: 72-84.

Årestedt, K., Alvariza, A., Boman, K. et al., 2018. Symptom relief and palliative care during the last week of life among patients with heart failure: A national register study. Journal of Pallitive Medicine. 21: 361-367.

Beccaro, M., Caraceni, A. and Costantini, M., 2010. End-of-life care in Italian hospitals: Quality of and satisfaction with care from the caregivers' point of view—Results from the Italian survey of the dying of cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 39: 1003-15.

Bello, A.K., Levin, A., and Lunney, M., 2019. Status of care for end stage kidney disease in countries and regions worldwide: International cross sectional survey. British Medical Journal. 367: 1-13.

Berman, S.J., Wada, C., Minatodani, D. et al., 2011. Home-based preventative care in high-risk dialysis patients: A pilot study. Telemedicine and e-Health. 17: 283–7.

Clarkson, K.A. and Robinson, K., 2010. Life on dialysis: A lived experience. Nephrology Nursing Journal. 37: 29-35.

Cheawchanwattana, A., et al., 2006. The validity of a new practical quality of life measure in patients on renal replacement therapy. Retrieved: www.kb.hsri.or.th

Cowan, D., Smith, L., and Chow, J., 2015. Care of a Patient’s Vascular Access for Haemodialysis: A Narrative Literature Review. Journal of Renal Care. 42: 93-100.

Creswell, J.W. and Plano Clark V.L., 2011. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Crowley, S.T., Belcher, J., Choudhury, D. et al., 2017. Targeting Access to Kidney Care Via Telehealth: The VA Experience. Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease. 24: 22-30.

Davison, S.N., 2010. End of life care preferences and needs: Perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clinical Journal of American Society of Nephrology. 5:195-204.

Frandsen, C.E., Pedersen, E.B., and Agerskov, H., 2020. When kidney transplantation is not an option: Haemodialysis patients' and partners' experiences—A qualitative study. Nursing Open. 7: 1110-1117.

Fung, Timothy KF, et al., 2017. Psychosocial factors predict nonadherence to PD treatment: A Hong Kong survey. Peritoneal Dialysis International. 37: 331-37.

Gerogianni, S. and Babatsikou, F., 2014. Social aspects of chronic renal failure in patients undergoing haemodialysis. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 7: 740-745.

Gullick, J., Monaro, S., and Stewart, G., 2016. Compartmentalising time and space: A phenomenological interpretation of the temporal experience of commencing haemodialysis. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 26: 3382-3395.

Han, E., Shiraz, F., Haldane, V. et al., 2019. Biopsychosocial experiences and coping strategies of elderly ESRD patients: A qualitative study to inform the development of more holistic and person-centred health services in Singapore. BMC Public Health. 19: 1-13.

Hirst, S.P., Lane, A.M., and Miller, C.A., 2015. Miller's nursing for wellness in older adults. Wolters Kluwer, 45: 151-158.

He, W., Goodkind, D., and Kowal P., 2016. An Aging World: 2015 International Population Reports. U.S. Government Publishing Office, Washington, DC.

Hoang, V.L., Green, T., and Bonner, A. 2019. Informal caregivers of people undergoing haemodialysis: Associations between activities and burden. Journal of Renal Care, 45: 151-158.

Hsu, H., Chu, T., Yen, J. et al., 2010. Development and implementation of a national telehealth project for long-term care: A preliminary study. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine. 97: 286-292.

Hunt, K.J., and Addington-Hall, J., 2011. A toolkit for the design and planning of locally-led VOICES end of life care surveys.

Hunt, K. J., Shlomo, N., and Addington-Hall, J., 2014. End-of-life care and preferences for place of death among the oldest old: Results of a population-based survey using VOICES-Short Form. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 17: 176-82.

Ishani, A., Christopher, J., Palmer, D. et al., 2016. Center for Innovative Kidney Care. Telehealth by an Interprofessional Team in Patients With CKD: A Randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 68: 41-9.

Jones, D.W., Harvey, K., Harris, J.P. et al., 2017. Understanding the impact of haemodialysis on UK National Health Service patients’ well-being: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 27: 193-204.

Johnston, M.J., King, D., Arora, S. et al., 2015. Smartphones let surgeons know WhatsApp: An analysis of communication in emergency surgical teams. The American Journal of Surgery. 209: 45-51.

Kang, X., Li, Z., and Nolan, M.T., 2011. Informal caregivers' experiences of caring for patients with chronic heart failure: Systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 26: 386-94.

Katon, W.J., Lin, E.H., Von Korff M., et al. 2010. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illness. The New England Journal of Medicine. 363: 261-2620.

Knodel, J., Teeraichitchainan, B., Prachuabmoh, V. et al., 2015. The situation of Thailand’s older population: An update based on the 2014 Survey of older persons in Thailand (Research report no.: 15-847), retrieved from University of Michigan Population Studies Center.

Kotanko, P., et al., 2007. Size matters: body composition and outcomes in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Blood purification. 25: 27-30.

Liyanage, T., Ninomiya, T., Jha, V. et al., 2015. Worldwide access to treatment for end stage kidney disease: A systematic review. Lancet. 385: 1975-82.

Miyashita, M., Morita, T., Sato, K. et al., 2015. A nationalwide survey of quality of end-of-life cancer care in designed cancer, inpatients pallitive care units, and home hospices in Japan: The J-HOPE study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 50: 38-47.e3.

Minatodani, D.E., Chao, P.J., and Berman, S.J., 2013. Home telehealth: facilitators, barriers, and impact of nurse support among high-risk dialysis patients. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health. 19: 573-8.

Marrufo, G., Colligan, E.M., Negrusa, B. et al., 2020. Association of the comprehensive end-stage renal disease care model with medicare payments and quality of care for beneficiaries with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Internal Medicine. 180: 852-860.

Murtagh, F. E. M., Addington-Hall, J., Donohoe, P. et al., 2006. Symptom management in patients with established renal failure managed without dialysis. Journal of Renal Care. 32: 93-8.

Murtagh, F.E.M., Addington-Hall, J. and Higginson, I.J, 2007. The prevalence of symptoms in end-stage renal disease: A systematic review. Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease. 14: 82-99.

Murtagh. F.E.M., Sheerin, N.S., Addington-Hall, J. et al., 2011. Trajectories of illness in stage 5 chronic kidney disease: A longitudinal study of patient symptoms and concerns in the last year of life. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 6: 1580-90.

Nephrology Society of Thailand, 2020. Annual reports on Thailand’s renal replacement therapy figures for the years 2016 to 2019[Online]. Available at: https://www.nephrothai.org/annual-report-thailand-renal-replacement-therapy-2007-2019-th/pdf (Accessed: 1 May 2021).

National Statistics Office, 2014. Ministry of Information and Communication Technology Older Persons in Thailand [Online]. Available at: http://web.nso.go.th/en/survey/age/tables_older_2014.pdf (Accessed: 13 January 2021).

Noble, H., Meyer, J., Bridges, J. et al., 2010. Exploring symptoms in patients managed without dialysis: a qualitative research study. Journal of Renal Care. 36: 9-15.

O’Neill, Jessica L, et al., 2014. Collaborative hypertension case management by registered nurses and clinical pharmacy specialists within the Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACT) model. Journal of general internal medicine. 29: 675-81.

Pungchompoo, W., 2013. Experiences and health care needs of older people with End Stage Renal Disease managed without dialysis in Thailand during the last year of life (University of Southampton).

Pungchompoo, W., 2014. Situation of Palliative Care in Thai Elderly Patient with End Stage Renal Disease. Nursing Journal. 41: 166-177.

Pungchompoo W., Richardson A., and Brindle L.A., 2016. Experiences and needs of older people with end stage renal disease: Bereaved carers perspective. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 22: 490-99.

Pungchompoo, W., et al., 2019. Experiences of symptoms and health service preferences among older people living with chronic diseases during the last year of life. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 25: 129-41.

Rifkin, D.E., et al., 2013. Linking clinic and home: a randomized, controlled clinical effectiveness trial of real-time, wireless blood pressure monitoring for older patients with kidney disease and hypertension. Blood pressure monitoring. 18: 8.

Roberts, D., Tayler, C., MacCormack, D. et al., 2007. Telenursing in hospice palliative care. The Canadian Nurse. 103: 24-7.

Saisunantararom, W., et al., 2015. Associations among spirituality, health-related quality of life, and depression in pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients: An exploratory analysis in Thai Buddhist patients. Religions. 6: 1249-62.

Swidler, Mark, 2009. Dialysis decisions in the elderly patient with advanced CKD and the role of nondialytic therapy. American Society of Nephrology Geriatric Nephrology Curriculum. 1-7.

Suwanrada, W., Pothisiri, W., Siriboon, S. et al., 2016. Evaluation of the replication project of the elderly home care volunteers. Bangkok: College of Population Studies, Chulalongkorn University.

Thiamwong, L. and Pungchompoo, W., 2018. Embedding palliative care into healthy aging: A narrative case study from Thailand. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 20: 416-20.

Tipseankhum, N., et al., 2016. Experiences of people with advanced cancer in home-based palliative care. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research. 20: 238-51.

Tousignant, M., et al., 2011. Patients' satisfaction of healthcare services and perception with in-home telerehabilitation and physiotherapists' satisfaction toward technology for post-knee arthroplasty: an embedded study in a randomized trial. Telemedicine and e-Health. 17: 376-82.

Tummalapali, S.L. and Ibrahim, S.A., 2020. Alternative Payment Models and Opportunities to Address Disparities in Kidney Disease. American Journal Kidney Disease. 1-10.

Weisbord, S.D., Mor, M.K., Sevick, M.A. et al., 2014. Associations of depressive symptoms and pain with dialysis adherence, health resource utilization, and mortality in patients receiving chronic hemodialysis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 9: 1594-1602.

World Health Organization, 2004. A community health approach to palliative care for HIV/AIDS and cancer patients in sub-Saharan Africa. A community health approach to palliative care for HIV/AIDS and cancer patients in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Health Organization. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42919. (Accessed: 5 May 2021).

Wu, Fan, Wu, Taiyang, and Yuce, Mehmet Rasit, 2019. An internet-of-things (IoT) network system for connected safety and health monitoring applications. Sensors, 19: 1-21.

Zalai, D., Szeifert, L., and Novak, M., 2012. Psychological distress and depression in patients with chronic kidney disease. Seminars in dialysis (25: Wiley Online Library). 428-38.

OPEN access freely available online

Chiang Mai University Journal of Natural Sciences [ISSN 16851994]

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

https://cmuj.cmu.ac.th

Wanicha Pungchompoo1* and Warawan Udomkhwamsuk2

1 Department of Medical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Chiang Mai University, Thailand.

2 Department of Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Corresponding author: Wanicha Pungchompoo, E-mail: wanicha.p@cmu.ac.th

Total Article Views

Editor: Veerasak Punyapornwithaya,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: February 25, 2021;

Revised: June 29, 2021;

Accepted: July 2, 2021;