Effectiveness of an Alcohol Relapse Prevention Program Based on the Satir Model in Alcohol-dependent Women

Soontaree Srikosai*, Darawan Thapinta, Phunnapa Kittirattanapaiboon and Nawanant PiyavhatkulPublished Date : 2019-08-25

DOI : 10.12982/CMUJNS.2014.0033

Journal Issues : Number 2,May-August-2014

Abstract

This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of an alcohol relapse prevention program based on the Satir Model on self-esteem, self-efficacy, life congruence and drinking behaviors by measuring heavy drinking days, abstinence days and levels of serum gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) in alcohol-dependent women. A randomized controlled trial was designed. Thirty-nine alcohol-dependent women hospitalized at either Suan Prung Psychiatric Hospital or Thanyarak Chiangmai Hospital, in Chiang Mai, Thailand, were randomly assigned into an experimental group of 18 women or a control group of 21 women. Results revealed that immediately following, and at 12 and 16 weeks after completing the alcohol relapse prevention program, participants in the experimental group demonstrated statistically significant increased self-esteem, self-efficacy and life congruence; increased abstinence days; and decreased heavy drinking days compared to the control group. In addition, at 16 weeks after completing the program, the experimental group had statistically significant lower levels of serum GGT than the control group. The alcohol relapse prevention program based on the Satir Model improved psychological health and prevented alcohol relapse among alcohol-dependent women.

Keywords: Alcohol-dependent women, Effectiveness, Relapse prevention, Satir Model

INTRODUCTION

Studies in Thailand and other countries indicate that significant risk factors for alcohol relapse in women include: (1) depression (Gjestad et al., 2011; Snow & Anderson, 2000; Zywiak et al., 2006); (2) stress from marriage and stress caused by an alcoholic spouse (Chansantor, 1998; Kamkan, 2005; Chowwilai, 2006; Walitzer & Dearing, 2006 and Jongchokdee, 2010); (3) low self-esteem (Angove & Fothergill, 2003; Silverstone & Salsali, 2003 and Jakobsson et al., 2008); (4) low self-efficacy (Scott, Foss, & Dennis, 2005; Moos & Moos, 2006; Mensinger et al., 2007 and Maisto et al., 2008); (5) disconnectedness (Masters & Carlson, 2006); and (6) psychological trauma caused by sexual/physical/emotional abuse (Chansantor, 1998; Knopik et al., 2004; Chowwilai, 2006).

Existing relapse prevention programs (from 2001 to 2010) were identified through literature reviews using Cochrane, Joannabrigs, PubMed, Science Direct and CINAHL database records, including database records from the Thai University Library Digital Collection and Thai journals. Using systematic review methods, five types of interventions were identified as significantly effective in stopping drinking when compared to control groups. However, none of these relapse prevention programs has been adopted in Thailand for a variety of reasons. Up to now, no intervention program has addressed factors specifically related to alcohol relapse in women.

Evidence indicates that women have difficulty coping with their internal feelings and emotions. Alcohol consumption is one way in which they try to cope with unpleasant emotions. Understanding that alcohol consumption is a coping phenomenon correlates well with the therapeutic belief about coping as established by the Satir Model, which states that the problem is not the problem; coping is the problem (Satir, 1983 and Satir et al., 1991). The Satir Model views symptoms of intra-psychic conflict – stress, depression, pain, trauma, conflict, suffering, low self-esteem and alcohol consumption – as a person’s way to cope with emotional pain or negative feelings. According to the Satir Model, alcohol-dependent women drink and relapse to drinking in order to cope with their intra-psychic conflict.

The Satir Model focuses on internal change. As literature reviews indicate, the Satir Model is appropriate for helping alcohol-dependent patients change their intra-psychic world. Using the iceberg as a metaphor for a person’s intra-psychic world, the Satir Model addresses a person’s yearnings, expectations, perceptions, feelings and feelings about feelings, as well as their survival coping patterns and behavior. Alcohol-dependent women continue to consume alcohol because they have unfulfilled yearnings, and drinking alcohol is their dysfunctional response to those feelings. However, if their yearnings are fulfilled, and a functional coping response can be established, then alcohol-dependent women can become positive choice makers. They are able to take responsibility for their internal and external world. They are more congruent, experience higher self-esteem and can relate empathetically with others (Satir, 1983 and Satir et al., 1991).

Five previous studies indicated that nursing intervention based on the Satir Model could effect intra-psychic change in alcohol-dependent patients. However, these studies also showed gaps of knowledge about the prevention of relapse among alcohol-dependent women. None of the programs had been designed to manage factors of alcohol relapse among women, the internal validity of the studies was also limited – there was no random allocation and none of the studies used a control group. Three studies did not address the variables of drinking behavior or alcohol relapse prevention. Furthermore, none focused on the inability to cope with psychological problems faced by alcohol-dependent women.

The state-of-the-art thinking about factors related to alcohol relapse among women indicate that alcohol relapse prevention programs need to be tailored to women by using a randomized controlled trial. In addition, currently existing alcohol relapse prevention programs do not specifically address factors of alcohol relapse in women that may lead to rapid relapse and more frequent re-admission. This study examines the effectiveness of an alcohol relapse prevention program based on the Satir Model on self-esteem, self-efficacy, life congruence, heavy drinking days, abstinence days and serum gamma-glutamyl transferase levels in alcohol-dependent women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and sample

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) design, double-blind clinical trial compares an alcohol relapse prevention program based on the Satir Model with regular care. First, the research assistants at each of the two research sites who interviewed participants to obtain data were blind to treatment allocation. Second, the participants in both groups did not know, or were blind to, which group they participated in.

Ethical Consideration. Data were collected after the research proposal had been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing, Chiang Mai University; Suan Prung Psychiatric Hospital; and Thanyarak Chiangmai Hospital.

Sample and setting. The sample was obtained from Suan Prung Psychiatric Hospital and Thanyarak Chiangmai Hospital, in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Fifty-one subjects agreed and 45 met inclusion criteria in this study. Thirty-nine subjects participated in this study and were interviewed at the baseline. Final analysis included only 27 subjects.

Inclusion included women dependent on alcohol at the mild to moderate level as assessed by the Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (SADQ), 25 years old or older, having almost low to almost high self-esteem, and almost low to almost high life congruence as measured by the Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory Adult Form and the Life Congruence Scale, respectively. Other inclusion criteria were having moderate to severe depressive symptoms as assessed by the PHQ-9, completing regular inpatient psychosocial care, having a psychiatrist or physician sign for discharge from the hospital, and having a spouse or family members who could participate in the program twice.

Participants were not recruited for the study if they received a diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, or received any of the following anti-relapse medication: Disulfiram, Topiramate or anti-craving medications.

Random allocation. Eighteen participants were randomly assigned to the experimental group and 21 participants to the control group by simple random sampling with replacement.

Instrument for data collection. The Timeline Follow-back interview (TLFB) was used to collect retrospective drinking information on alcohol use 30 days prior to hospitalization. The TLFB, developed by Sobell and Sobell (Gmel & Rehm, 2004), has been found to have high test-retest reliability and concurrent validity across multiple populations of drinkers (Klein et al., 2007). Heavy drinking for women in this study is defined as ≥ 4 drinks during one occasion (Gmel & Rehm, 2004; Sommers 2005; WHO, 2001).

Laboratory testing was used to evaluate the level of serum GGT. The GGT is a biochemical measurement that is not vulnerable to problems of inaccurate recall or reluctance of individuals to give candid reports of their drinking behaviors or attitudes (Gmel & Rehm, 2004). In this study, the GGT blood test was conducted twice: before being discharged from the hospital, which averaged 4-6 weeks of inpatient treatment; and at 16 weeks after program completion.

The Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory Adult Form is a rating scale of 25 items developed by Coopersmith (1984). This scale is based on the definition of ‘self-esteem’ as defined by Coopersmith, which is similar to Satir’s definition (Satir & Baldwin, 1983). The SEI-Adult Form consists of four components of the self – specifically, social, academic, family and personal areas of experience. The total scale scores range from 25 to 150, with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem. This scale was translated into Thai and tested for reliability by Wongleakpai (1989). The researcher evaluated the validity of the Thai version of the SEI-Adult form by calculating the content validity index (CVI) from opinions of six experts. The mean of item-level CVI was 0.75 and the scale-level CVI was 0.75. The reliability of this scale was determined by a one-week test-retest, and the internal consistency was estimated with 10 alcohol-dependent women. The correlation coefficient was 0.88 (p = 0.01); the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.81.

The General Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale is a rating scale developed by Matthias Jerusalem and Ralf Schwarzer in 1981. It is a 4-point rating scale with 10 items to assess perceived self-efficacy regarding coping and adaptation abilities in both daily activities and isolated stressful events. The scale is designed for adults and adolescents ≥ 12 years of age. The total scale scores range from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating stronger belief in self-efficacy. This scale was translated into a Thai version by Sukmak et al. (2002) and it was administered to 103 amphetamine-dependent patients for components and confirmatory factor analyses. The researcher tested the internal consistency reliability of this scale among 10 alcohol-dependent women before using it in this study. The Chronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.86.

The Life Congruence Scale is a rating scale developed by Lee (2002), a 7-point rating scale with 21 items. This scale is based on the ‘congruence concept’ of the Satir Model. The original, 75-item congruence scale developed by Lee was translated into a Thai version and the psychometric properties of the scale were determined by Srikosai and Taweewattanaprecha (2011). The scale has five dimensions: intrapsychic, interpersonal, spiritual, creative and communal. The total scores range from 21 to 147, with higher scores indicating higher life congruence. The validity and reliability of the Thai version of the Life Congruence Scale were established and high (Srikosai & Taweewattanaprecha, 2011). The reliability of the Thai version of the Life Congruence Scale was determined by an internal consistency estimate with 10 alcohol-dependent women from Suan Prung Psychiatric and Thanyarak Chiangmai Hospitals. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.81.

Data analysis: Descriptive statistics, t-test, Two-Way Repeated-Measures ANOVA (Mix Model) and Mann-Whitney U test.

Procedure for developing the program

(1) Review Satir Model concepts, the therapeutic beliefs of the Satir Model and related literature. (2) Develop the first draft in English. This step was required to get the input a non-Thai speaking expert who was essential to developing an effective protocol. (3) Submit the English version and a research proposal to six experts for process evaluation in the areas of language, feasibility and appropriateness. (4) Revise the English program based on the recommendations and suggestions of the experts. (5) Test with four alcohol-dependent women for feasibility and appropriateness. (6) Develop a Thai version from the English version and from the outcomes of testing in order to get a protocol intended for women with alcohol dependence who are Thai, speak Thai and come from a Thai cultural context. (7) Submit the Thai version to six Thai experts to examine the process for language, feasibility and appropriateness. (8) Revise the Thai version based on the suggestions of experts. (9) Test again with four alcohol-dependent women for feasibility and appropriateness.

RESULTS

Thirty-nine participants ranged in age from 25 to 60 years, with an average age of starting to drink of 18 years. Nineteen participants were married. A similar number were divorced/widowed and single. Twenty-six participants completed primary school and most participants worked in agriculture. A majority had income lower than THB 3,000 (USD 93) per month and never smoked. Most of participants stated that the cause of their drinking or re-drinking was stress, followed by persuasion from friends or spouse. The number of one-time and multiple admissions were similar, and the diagnoses were alcohol dependence (F10.2) and alcohol dependence and alcohol-induced psychotic disorder (F10.2 and F10.5) (61.5% and 25.6%, respectively). No aspects of the demographic characteristic of participants in the experimental group were different from participants in the control group.

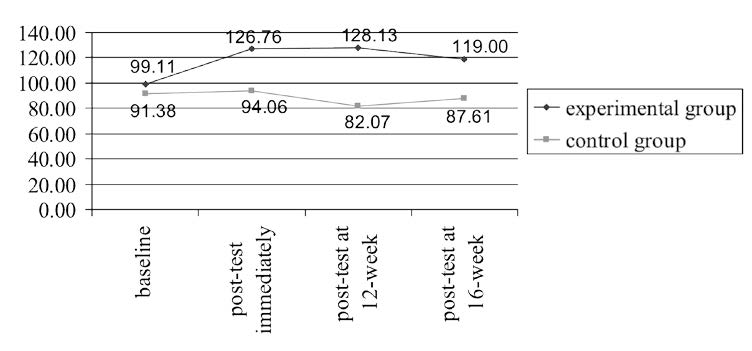

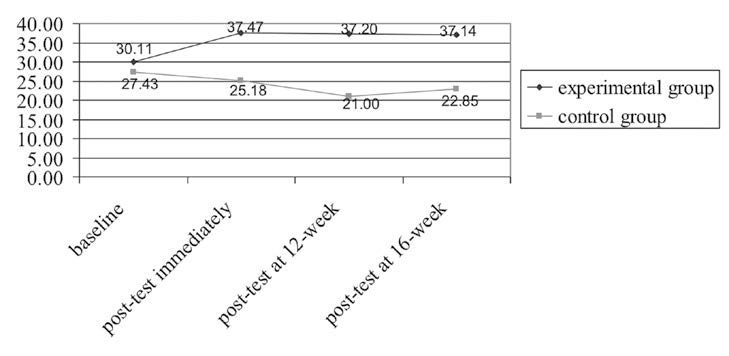

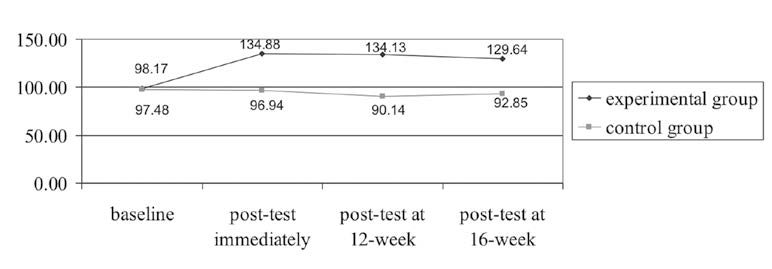

The scores of self-esteem, self-efficacy and life congruence in the experimental group were significantly higher than the control group at the post-est immediately after completing the program, and at 12 and 16 weeks after program completion (Figure 1, 2, 3).

Figure 1. Change in overall self-esteem scores of the experimental and control groups over time.

Figure 2. Change in overall self-efficacy scores of the experimental and control groups over time.

Figure 3. Change in overall life congruence scores of the experimental and control groups over time.

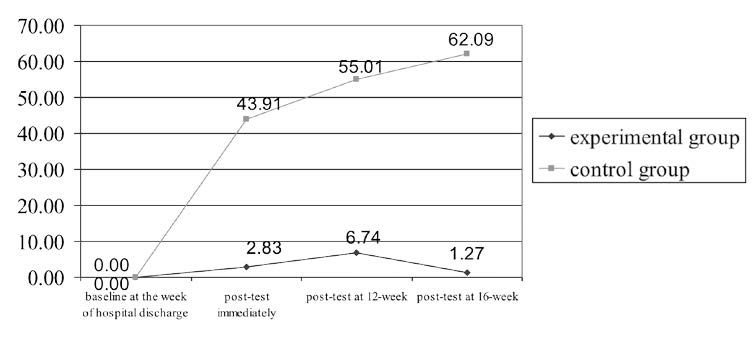

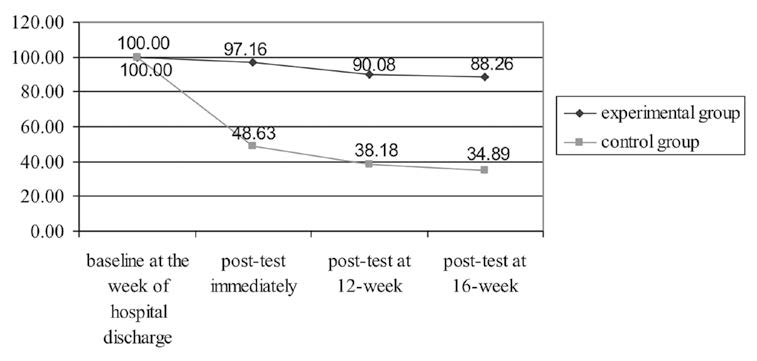

The scores of percent of heavy drinking days in the experimental group were significantly lower than the control group at post-test immediately after completing the program, and at 12 and 16 weeks after program completion (p < 0.01) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Change in overall percent of heavy drinking days of the experimental and control groups over time.

The scores of percent of abstinence days in the experimental group were significantly higher than the control group at post-test immediately after completing the program, and at 12 and 16 weeks after program completion (p < 0.01) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Change in overall percent of abstinence days of the experimental and control groups over time.

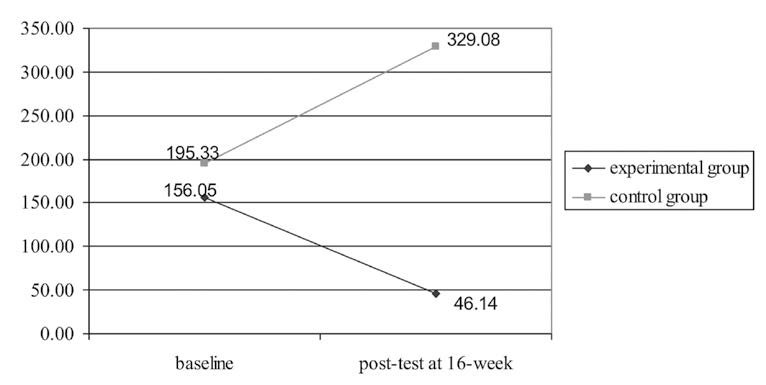

The level of serum GGT in the experimental group was significantly lower than the control group at 16 weeks after program completion (p < 0.001) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Change in overall level of serum gamma-glutamyl transferase of the experimental and control groups over time.

DISCUSSION

Participants in the experimental group had significantly higher self-esteem, self-efficacy and life congruence at immediate post-test, and at 12 and 16 weeks after program completion, than participants in the control group, which indicates that an alcohol relapse prevention program based on the Satir Model is effective over time on increasing self-esteem, self-efficacy and life congruence, when compared to regular care. A possible explanation is that the participants continued to experience their own positive life energy. They were able to cope well with intra-psychic conflict and utilize their improved coping styles because their yearnings were fulfilled. This was achieved by the therapist using five essential elements in each therapy session, including ‘positive directional goals’, ‘systematic approach’, ‘internal experiential’, ‘change focused’ and ‘the use of self’. The therapist facilitated the participants’ increased self-esteem and self-acceptance as a step for the patients to learn to fulfill their other yearnings by themselves. When an individual’s yearnings are fulfilled, then realistic and positive expectations to the self, to others and from others are present. These changed expectations can affect perceptions of reality, and positive directional feelings and positive feelings about feelings can eventually be achieved (Satir, 1983; Satir et al., 1991).

These findings support previous studies that found that five alcoholdependent women who received two to three therapy sessions based on the Satir Model had higher mean scores of self-esteem compared to baseline scores (73.40 versus 91.40) (Srikosai & Taweewattanaprecha, 2012) and five patients with alcohol problems who received five sessions of couples therapy based on the Satir Model increased self-esteem from relatively low scores to relatively high scores (Bangsaeng, 2010). A woman with mixed anxiety/depressive disorder, after being treated with the Satir Model, could accept herself and feel more confidence, pride and independence. These changes decreased her depression and anxiety (Jainkitjapaiboon, 2009). Alcohol-dependent men and their family members, after completing family therapy based on the Satir Model, had better self-esteem scores and perceptions about family function (Patmanee, 2009). Furthermore, Taiwanese women who experienced an educational program based on the Satir Model achieved internal change or positive self-growth through non-defensive acceptance of their family of origin. They could recognize and accept themselves, and accept their family members as they were. They became aware of change and could make positive changes towards internal growth (Pei, 2008).

Participants in the experimental group had significantly less heavy drinking days and increased abstinence days at an immediate post-test, and at 12 weeks and 16 weeks after program completion than participants in the control group. Apossible explanation is that higher self-esteem, self-efficacy and life congruence are associated with changes in drinking behaviors. Based on the Satir Model (Satir, 1983; Satir et al., 1991), if yearnings are fulfilled, then positive expectations are present and perception of reality increase. Positive directional feelings and feelings about feelings will be achieved and congruent survival coping stance will be used, and these lead to healthy behavior – choosing not to drink. The interaction of each level of the iceberg also leads to becoming a positive choice-maker, taking responsibility for one’s internal and external world, being more congruent and experiencing higher self-esteem. Participants in the experimental group showed the ability to control drinking during the program.

Participants in the experimental group had significantly lower levels of serum gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) 16 weeks after program completion (p < 0.001) than participants in the control group. This finding is the result of increased alcohol abstinence and decreased heavy drinking, consistent with the literature, which states that after 2-6 weeks of abstinence, levels of GGT generally decrease to within the normal reference range (Gmel & Rehm, 2004; Kranzler & Tennen, 2005). A systematic review of studies found that the GGT level is a more sensitive marker for heavy drinking in women than carbohydrate-deficient transferring (CDT). In addition, the sensitivity of GGT in women is 60 percent versus 52 percent sensitivity for the macrocytic volume (MCV). The GGT test, therefore, appears to be the most appropriate single biological marker to assess mid-term and long-term drinking in women (Sommers, 2005). If participants have increased alcohol abstinence days or decreased heavy drinking days, less serum GGT leaks across the cell membrane into the blood (Allen et al., 2003). Therefore, the effects of an alcohol relapse prevention program based on the Satir Model on drinking behaviors have strong reliability because lower GGT levels were present.

CONCLUSION

These research results add new knowledge that an alcohol relapse prevention program based on the Satir Model leads to higher self-esteem, self-efficacy and life congruence; fewer heavy drinking days; more abstinence days and a decrease in GGT levels among alcohol-dependent women. This program should be used as a nursing intervention for female patients with alcohol dependence hospitalized in psychiatric hospitals or hospitals for alcohol and drug dependence treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Center for Alcohol Studies for financial support of this study.

REFERENCES

Allen, J. P., P. Sillanaukee, N. Strid, and R.Z. Litten. 2003. Biomarkers of heavy drinking. In J.P. Allen and V.B. Wilson (Eds.), Assessing alcohol problems: A guide for clinicians and researchers (pp. 37-53). (2nd ed.). National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health.

Angove, R., and A. Fothergill. 2003. Women and alcohol: Misrepresented and misunderstood. Journal of Psychiatry and Mental Health Nursing, 10(2), 213-219.

Banmen, J. 2007. If depression is the solution, what are the problems? The Satir Journal, 1(2), 61-81.

Bangsaeng, S. 2010. Couple therapy for patient with alcohol user admitted in Khon Kaen Rajanakarind Psychiatric Hospital based on Satir’s Model. Master’s independent study, Khon Kaen University, Thailand.

Banmen, J., and K. Maki-Benmen. 2006. Application of the Satir Growth Model introduction. Retrieved May 12, 2011, from http://www.satir.

Chansantor, A. 1998. Contributing factors to and effects of alcohol dependence among women. Master’s thesis, Chiang Mai University, Thailand.

Chouwilai, J. 2006. The alcohol consumption: as a factor of domestic violence. In Center for Alcohol Studies (Ed.), The Second National Alcohol Conference: Alcohol Consumption and Related problems in Thailand (pp. 48-49), 13-14 December, 2006. Rama Garden Hotel, Bangkok, Thailand.

Coopersmith, S. 1984. SEI: Self-esteem inventory. California: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Ford, S. 2007. Satir in the Sand Tray: facilitating peace within. The Satir Journal, 1(3), 2-26.

Gjestad, R., J. Franck, K.A. Hagtvet, and B. Haver. 2011. Level and change in alcohol consumption, depression and dysfunctional attitudes among females treated for alcohol addiction. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 46(3), 292-300.10.1093/alcalcagr018

Gmel, G., and J. Rehm. 2004. Measuring alcohol consumption. In contemporary drug problems (pp. 467-474), 31(3). New York: Fall.

Jakobsson, A., G. Hensing, and F. Spak. 2008. The role of gendered conceptions in treatment seeking for alcohol problems. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 22(2), 196-202. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00513.X

Jainkitjapaiboon, P. 2009. Individual Psychotherapy with Satir Model: Case study of the patient with mixed anxiety depressive disorder. Bulletin of Suan Prung, 25(1), 90-104.

Jongchokdee, P. 2010. The effectiveness of stress inoculation training program among wives of patients with alcohol dependence. Master’s thesis, Burapa University, Thailand.

Kamkan, J. 2005. The socio-cultural context affecting on alcohol drinking behavior in the worker of Dongkilek village, Chachang Sub-district, San Kamphaeng District, Chiang Mai Province. Master’s independent study, Chiang Mai University, Thailand.

Klein, A.A., P.R. Stasiewicz, J.R. Koutsky, C.M. Bradizza, and S.F. Coffey. 2007. A psychometric evaluation of the Approach and Avoidance of Alcohol Questionnaire (AAAQ) in alcohol dependent outpatients. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29, 231-240. 10.1007/S10862-007-9044-2

Knopik, V.S., A.C. Heath, P.A.F. Madden, K.K. Bucholz, W.S. Slutske, E.C. Nelson, and et al. 2004. Genetic effects on alcohol dependence risk: re-evaluating the importance of psychiatric and other heritable risk factors. Psychological Medicine, 34(8), 1519-1530. 10.1017/S0033291704002922

Kranzler, H. R., and H. Tennen. 2005. How to measure relapse in humans. In R. Spanagel & K.F. Mann (Eds.), Drugs for relapse prevention of alcoholism (pp. 23-39). Basel: Birkhauser Verlag.

Lee, B.K. 2002. Development of a congruence scale based on the Satir Model. Contemporary Family Therapy, 24(1), 217-239. 10.1023/A:1014390009534

Maisto, S.A., P.R. Clifford, R.L. Stout, and C.M. Davis. 2008. Factor mediating the association between drinking in the first year after alcohol treatment and drinking at three years. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 52(1), 728-737.

Masters, C., and D.S. Carlson. 2006. The process of reconnecting: recovery from the perspective of addicted women. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 17(4), 205-210. 10.1080/10884600600995200

Mensinger, J.L., K.G. Lynch, T.R. TenHave, and J.R. McKay. 2007. Mediators of telephone-based continuing care for alcohol and cocaine abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(5), 775-784. Retrieved July 23, 2010, rom NIH Public Assess: Author Manuscript. 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.775

Moos, R.H., and B.S. Moos. 2006. Rates and predictors of relapse after natural and treated remission from alcohol use disorders. Addiction, 101(2), 212-222. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01310.X

Patmanee, K. 2009. Family therapy in family with alcohol dependence patient based on Satir Model. Master’s independent study, Khon Kaen University, Thailand.

Pei, Y. 2008. From caterpillar to butterfly: Action research study of a Satir-based women’s program in Taiwan. The Satir Journal, 2(1), 55-107.

Satir, V. 1983. Conjoint family therapy. (3rd ed.). Palo: Science and Behavior Books.

Satir, V., and S.M. Baldwin. 1983. Satir step by step: A guide to creating change in families. Palo Alto: Science and behavior books.

Satir, V., Banmen, J., Gerber, J., & Gomori, M. 1991. The Satir Model: Family therapy and beyond. California: Science and behavior book.

Scott, C.K., M.A. Foss, and M.L. Dennis. 2005. Pathways in the relapse-treatment-recovery cycle over 3 years. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 28, S63-S72. 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.09.006

Silverstone, P. H., and M. Salsali. 2003. Low self-esteem and psychiatric patients: Part I The relationship between low self-esteem and psychiatric diagnosis. Annals of General Hospital Psychiatry, 2(2), doi:10.1186/1475-2832-2-2

Snow, D., and C. Anderson. 2000. Exploring the factors influencing relapse and recovery among drug and alcohol addicted women. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services, 38(7), 8-19.

Sommers, M.S. 2005. Measurement of alcohol consumption: Issues and challenges. In J.J. Fitzpatrick (Series Ed.), Annual review of nursing research (Volume 23): Alcohol use, Misuse, Abuse, and Dependence (pp. 27-64). New York: Springer.

Srikosai, S., and S. Taweewattanaprecha. 2012. Internal change among alcohol-dependent persons receiving Satir Transformational Systemic Therapy: a case study of inpatients. Suan Prung Psychiatric Hospital, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Srikosai, S., and S. Taweewattanaprecha. 2011. Psychometric evaluation of the Life-Congruence Scale based on the Satir Model: Thai version. Journal of the Psychiatric Association of Thailand, 56(3), 21-30.

Sukmak, V., A. Sirisoonthon, and P. Meena. 2002. Validity of the general perceived self-efficacy scale. Journal of the Psychiatric Association of Thailand, 47(1), 31-37.

Walitzer, K.S., and R.L. Dearing. 2006. Gender differences in alcohol and substance use relapse. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 128-148. 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.003

Wongleakpai, N. 1989. Effects of the relationship group on self-esteem among youth. Master’s thesis, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand.

WHO. 2001. Why screen for alcohol use?. In B. F. Thomas, H-B. C. John, S. B. John, & N. G. Maristela (Eds.), AUDIT, The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care (pp. 5-9). (2nd ed.). Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence.

Zywiak, W.H., R.L. Stout, W.B. Trefry, I. Glasser, G.J. Connors, and S.A. Maisto, et al. 2006. Alcohol relapse repetition, gender, and predictive validity. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(4), 349-353. 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.004

Soontaree Srikosai1*, Darawan Thapinta1, Phunnapa Kittirattanapaiboon2 and Nawanant Piyavhatkul3

1 Faculty of Nursing, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand

2 Department of Mental Health, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi 11000, Thailand

3 Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand

*Corresponding author. E-mail: s.srikosai@gmail.com

Total Article Views