Effectiveness of an Emergency Illness Prevention Program among Older Adult Caregivers in Northern Thailand

Rossarin Kaewta, Waraporn Boonchieng*, Kannikar Intawong, Noppcha Singweratham, and Sunisa ChansaengPublished Date : October 1, 2025

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2026.005

Journal Issues : Number 1, January-March 2026

Abstract This quasi-experimental study evaluated the effectiveness of an emergency illness prevention program among caregivers of older adults in Northern Thailand. The sample consisted of 120 primary caregivers of older adults living in Northern Thailand were recruited through purposive sampling and divided equally into an experimental group and a control group, with 60 people per group, based on the inclusion criteria. The experimental group received a participatory emergency illness prevention program that was conducted for 10-weeks intervention. Data were collected by using validated questionnaires administered pre- and post-intervention. The instruments showed good reliability: KR-20 = 0.81 for knowledge, Cronbach’s α = 0.87 for self-efficacy, and 0.89 for outcome expectations. The data were analyzed with descriptive statistics, paired t–test, and independent t–test statistics.

The results showed that, post-intervention, the experimental group demonstrated significant improvements in the average scores of knowledge (P<0.001), self-efficacy (P<0.001), and outcome expectations (P<0.001), compared to the control group, which showed no significant changes. Moreover, the pre–post comparison within the experimental group revealed significant improvements across all three outcomes (P<0.001).

The participatory emergency illness prevention program effectively improved caregivers’ capacity to manage emergency conditions in older adults. Integrating the program developed in this study into community health frameworks may enhance elderly care and reduce adverse outcomes.

Keywords: Caregivers, Older adult, Emergency illness, Knowledge, Outcome expectation, Self-efficacy

Graphical Abstract:

Citation: Kaewta, R., Boonchieng, W., Intawong, K., Singweratham, N., and Chansaeng, S. 2026. Effectiveness of an emergency illness prevention program among older adult caregivers in Northern Thailand. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 25(1): e2026005.

INTRODUCTION

Thailand is undergoing a demographic transition into an aging society, with individuals aged 60 years and older accounting for about 20% of the total population in 2024 (Department of Older Persons, 2024; National Statistical Office, 2025; Pruksacholavit, 2025). This shift has led to an increased prevalence of chronic illnesses and functional limitations, reducing independence in activities of daily living (ADLs) and heightening the need for sustained caregiving support (Lumjeaksuwan et al., 2021; Edemekong, 2023). Family caregivers therefore play a crucial role in meeting the physical, emotional, and social needs of older adults.

Globally, caregivers are recognized as central to elder care but often lack training and support, resulting in substantial burden and stress (Bevans and Sternberg, 2012; Adelman et al., 2014; Choi et al., 2024; Cui et al., 2024). Similar challenges are evident in Thailand, particularly in rural areas where access to formal services is limited, and caregivers frequently report high stress and insufficient preparedness (Aung et al., 2022; Ruangritchankul and Pramotesiri, 2024). Evidence consistently shows that caregiver well-being directly shapes patient outcomes, with effective caregiver support linked to better treatment adherence, reduced hospital readmissions, and enhanced quality of life, whereas caregiver stress undermines recovery and psychological health (Bevans and Sternberg, 2012; Northouse et al., 2012; Adelman et al., 2014). These findings underscore that caregiver well-being is not only vital for caregivers themselves but also directly determines the health trajectories of older adults.

Emergency health situations further intensify these challenges. In 2023, Thailand reported more than 1.2 million emergency cases, nearly one-quarter involving older adults, commonly due to falls, strokes, and acute cardiac events (Lumjeaksuwan et al., 2021; National Institute for Emergency Medicine, 2024). Yet many informal caregivers remain unprepared to recognize early warning signs or respond promptly (Pleasant et al., 2020; Sathagathonthun et al., 2021). Strengthening caregivers’ self-efficacy—defined by Bandura (1997) as the belief in one’s ability to organize and execute actions to manage challenging situations—is critical for improving preparedness and care quality. Self-efficacy, shaped by mastery experiences, observation, verbal persuasion, and emotional regulation, has been shown to enhance confidence, persistence, and problem-solving ability, thereby improving both caregiver readiness and care outcomes (Sathagathonthun et al., 2021; Wright et al., 2021). Educational interventions—particularly those using simulations and scenario-based training—have further demonstrated effectiveness in increasing caregiver competence and reducing burden (Pleasant et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2021).

In Thailand, policy initiatives and community pilot programs have emerged to address caregiver training gaps but remain limited in scale (Sanpunya et al., 2022; Suna et al., 2025). Locally relevant, evidence-based programs are therefore urgently needed, as community-based initiatives have shown success in empowering caregivers and integrating eldercare into the primary care system (Aung et al., 2022; Sanpunya et al., 2022). Prior studies highlight the benefits of structured caregiver guidelines and training (Doungchan et al., 2021; Sathagathonthun et al., 2021; Thummakul et al., 2025), while participatory and scenario-based approaches demonstrate improved engagement, knowledge, and competence (Sanpunya et al., 2022; Pongtriang et al., 2024). This study was developed in collaboration with a geriatric health expert, who guided curriculum design, content validation, and activity planning to ensure contextual relevance and rigor.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of an emergency illness prevention program on caregivers’ knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations. Specifically, it examined changes in knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations among caregivers in the experimental group before and after the intervention. Additionally, the study compared these outcomes between the experimental and control groups following the intervention. The findings are expected to provide valuable insights for advancing broader strategies that enhance caregiver readiness and strengthen community-based care systems for older adults in Thailand.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design

This quasi-experimental study employed a two-group, pre-test and post-test design to evaluate the effectiveness of the emergency illness prevention program on knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations among caregivers of older adults in Northern Thailand.

Population and sample

The population consisted of older adults primary caregivers aged 20 years and above residing in Mae Chai District, Phayao Province, Northern Thailand. The sample comprised 120 older adults primary caregivers, purposively recruited from two target subdistricts in Mae Chai District. For this study, a “primary caregiver” was defined as a family member who had been primarily responsible for the daily care of an older adult.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) age 20 years or older; (2) being the primary caregiver of an older adults aged 60 years or above, providing at least three hours of daily care; (3) ability to communicate in Thai; and (4) willingness to participate in all study activities. Exclusion criteria were: (1) being a professional or paid caregiver and (2) having a serious illness.

The sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007), assuming a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5), α = 0.05, power = 0.80, and two-tailed testing, which indicated a minimum of 102 participants. To account for potential attrition, the sample size was increased to 120.

The study sites were Maesuk and Pa Faek Subdistricts in Mae Chai District, Phayao Province, purposively selected due to their high proportion of older adults requiring caregiving, the availability of caregiver networks, and strong collaboration with local health authorities, which facilitated program implementation.

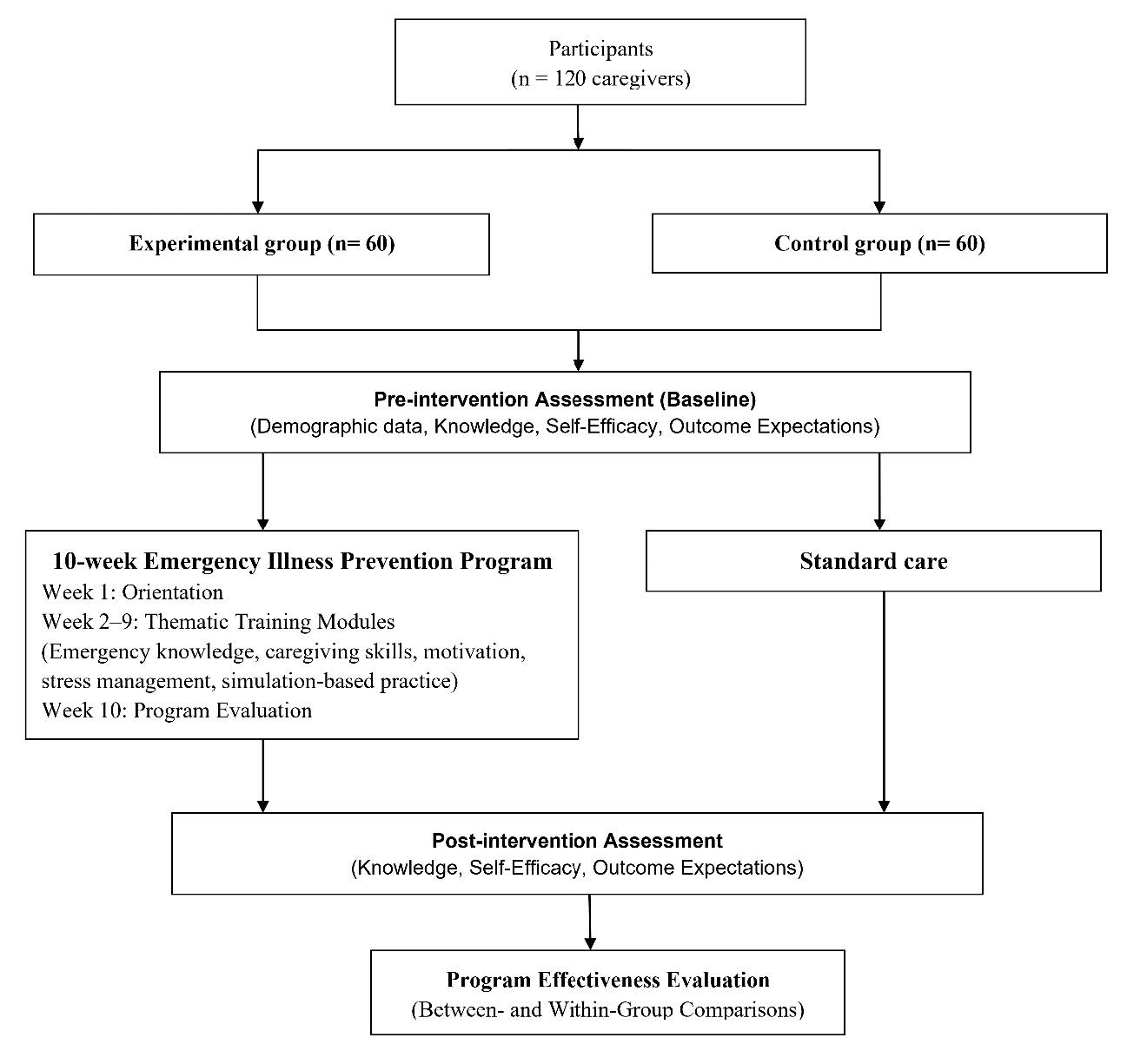

A total of 120 participants were purposively selected and equally assigned to the experimental group (n = 60) and the control group (n = 60). The intervention was implemented over a 10-week period. The control group received standard care based on guidelines routinely practiced in the institution, including routine health education provided by local health authorities, which typically covered basic information on elderly care, nutrition, medication use, and illness prevention. Both groups completed the same validated questionnaires before (pre-test) and after (post-test) the intervention. The flow of the study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the 10-week emergency illness prevention program.

Research instruments

The instruments used in this study were divided into two parts: (1) data collection instruments and (2) program structure and implementation.

Part I: Data collection instruments

1.1 Demographic Data Questionnaire: A structured questionnaire developed by the research team collected information on seven variables: age, gender, marital status, educational level, occupation, monthly income, and number of underlying health conditions.

1.2 Knowledge Questionnaire on Emergency Illness in Older Adults: This 15-item instrument was developed by the research team based on an extensive review of relevant literature and expert consultation. The items addressed causes, risk factors, clinical manifestations, emergency responses, and preventive measures. Dichotomous response options (true/false) were provided, with correct answers scored as 1 and incorrect answers as 0. Knowledge levels were categorized according to Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom, 1956) as high (≥80% of total score), moderate (60–79%), and low (<60%). Content validity, assessed by five experts in geriatric care, emergency nursing, and community health, yielded a Scale-Level Content Validity Index (S-CVI) of 0.89. Internal consistency was confirmed using the Kuder–Richardson Formula 20 (KR-20), with a coefficient of 0.81.

1.3 Self-Efficacy Questionnaire: This instrument was developed based on Bandura’s self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1997) and was adapted to reflect caregiving tasks for older adults, such as medication management and emergency response. A panel of five experts in geriatric care, emergency nursing, and community health reviewed the questionnaire, confirmed its contextual relevance, and finalized 20 positively worded items, which were rated using a five-point Likert scale (1 = very low ability to 5 = very high ability). The items were classified into three domains: (1) self-efficacy in emergency assessment (items 1–4, 13–14), (2) self-efficacy in first aid (items 5–12, 15), and (3) self-efficacy in help-seeking and self-regulation (items 16–20). Scores were interpreted according to Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom, 1956): high (≥80%), moderate (60–79%), and low (<60%). Content validity was strong (S-CVI = 0.92), and Cronbach’s alpha indicated high internal consistency (α = 0.87).

1.4 Outcome Expectation Questionnaire: This 15-item instrument, developed with reference to Bandura’s theoretical framework and reviewed by experts, measured caregivers’ expectations regarding the outcomes of caregiving practices. The items were classified into three domains: (1) outcome expectation in emergency response (items 1–5), (2) outcome expectation in first aid and resuscitation (items 6–9), and (3) outcome expectation in prevention and family preparedness (items 10–15). Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very low expectation) to 5 (very high expectation). Scores were categorized into three levels following Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom, 1956): high (≥80%), moderate (60–79%), and low (<60%). Content validity, confirmed by the expert panel, yielded an S-CVI of 0.94, and Cronbach’s alpha indicated strong internal consistency (α = 0.89).

Part II: Program structure and implementation

The Emergency Illness Prevention Program was conducted over a 10-week period to strengthen caregivers’ knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations. Participatory learning strategies were employed, including lectures, group discussions, demonstrations, hands-on practice, case sharing, and simulation exercises. The curriculum was developed with input from geriatric care specialists to ensure contextual and cultural appropriateness (Table 1). Each session lasted approximately 2–3 hours and was conducted in small groups of 10–12 participants to promote active learning and peer interaction. The program was delivered by experienced nurse instructors in collaboration with community health officers. Instructional materials included printed manuals, case-based scenarios, video presentations, and demonstration kits, all of which were tailored to rural caregiving contexts.

Table 1. Summary of weekly program contents and key learning activities.

|

Week |

Session Topic |

Key Content/Activities |

|

1 |

Introduction |

|

|

2 |

Emergency Conditions in Older Adults |

|

|

3 |

Emergency Care for Older Adults I |

|

|

4 |

Emergency Care for Older Adults II |

|

|

5 |

We Can Do It and Do It Well (Enactive Mastery Experiences) |

|

|

6 |

Observational Learning Activity (Vicarious Experiences) |

|

|

7 |

Confidence-Building Activity (Verbal Persuasion) |

|

|

8 |

Emotional Empowerment Activity (Emotional Arousal) |

|

|

9 |

Enhancing Outcome Expectation Activity |

|

|

10 |

Knowledge Sharing and Reflection Activity |

|

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using two main statistical approaches. First, demographic data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, and group comparisons were performed using inferential statistics, specifically the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and the independent samples t-test for continuous variables. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicated that all outcome variables (knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations) were normally distributed (P>0.05). A paired samples t-test was used to compare differences in knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations between the pre-intervention and post-intervention phases within the experimental group. An independent samples t-test was then used to compare the mean scores of knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations between the experimental and control groups. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Ethical consideration

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board of the Faculty of Public Health, Chiang Mai University (Approval No. ET062/2023)

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

A total of 120 participants were enrolled in the study, with 60 assigned to the experimental group and 60 to the control group. As presented in Table 2, no significant differences were observed between groups in demographic characteristics, confirming baseline comparability.

The majority of participants were female (88.33% in the control group and 91.67% in the experimental group). The mean ages were 52.85 years (SD = 8.71) in the control group and 54.46 years (SD = 9.27) in the experimental group. Most participants had completed secondary school (50.00% and 56.66%, respectively) and were living with their spouses (60.00% and 70.00%, respectively). Agriculture was the most common occupation in both groups (55.00% in the control group and 51.62% in the experimental group). Regarding income, the majority reported earning less than 10,000 baht per month (90.00% and 93.33%, respectively). In terms of health status, most participants reported having two chronic conditions (58.33% in the control group and 41.67% in the experimental group).

Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests showed no statistically significant differences between groups across demographic or health-related variables (P>0.05).

Table 2. Demographic variables of the control and the experimental group.

|

Demographic Characteristics |

Control (n = 60) |

Experimental (n = 60) |

P-value |

||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

0.543a |

|

Male |

7 |

11.67 |

5 |

8.33 |

|

|

Female |

53 |

88.33 |

55 |

91.67 |

|

|

Age (years) |

|

|

|

|

0.150a |

|

30 – 39 |

4 |

6.67 |

6 |

10.00 |

|

|

40 – 49 |

17 |

28.33 |

7 |

11.67 |

|

|

50 – 59 |

24 |

40.00 |

29 |

48.33 |

|

|

60 years and older |

15 |

25.00 |

18 |

30.00 |

|

|

Min - Max |

(37 - 69) |

(31 - 69) |

|

||

|

Mean (SD) |

52.85 (8.71) |

54.46 (9.27) |

|

||

|

Education level |

|

|

|

|

0.934a |

|

Primary school and lower |

20 |

33.33 |

18 |

30.00 |

|

|

Secondary school |

30 |

50.00 |

34 |

56.66 |

|

|

Diploma |

4 |

6.67 |

3 |

5.00 |

|

|

Graduate and above |

6 |

10.00 |

5 |

8.34 |

|

|

Marital status |

|

|

|

|

0.496a |

|

Single |

12 |

20.00 |

10 |

16.67 |

|

|

Lived with their spouse |

36 |

60.00 |

42 |

70.00 |

|

|

Separated from their spouses |

12 |

20.00 |

8 |

13.33 |

|

|

Occupational status |

|

|

|

|

0.755a |

|

Unemployed/housewife |

9 |

15.00 |

13 |

21.69 |

|

|

Agriculture |

33 |

55.00 |

31 |

51.62 |

|

|

General laborer |

12 |

20.00 |

12 |

20.00 |

|

|

Merchant/Self-employed |

6 |

10.00 |

4 |

6.69 |

|

|

Monthly income (baht/month) |

|

|

|

|

0.579b |

|

≤ 5,000 |

37 |

61.67 |

44 |

73.33 |

|

|

5,001 – 10,000 |

17 |

28.33 |

12 |

20.00 |

|

|

10,001 – 15,000 |

5 |

8.33 |

3 |

5.00 |

|

|

≥ 15,001 |

1 |

1.67 |

1 |

1.67 |

|

|

Number of chronic conditions of older adults |

|

|

|

|

0.370b |

|

1 |

9 |

15.00 |

13 |

21.67 |

|

|

2 |

35 |

58.33 |

25 |

41.67 |

|

|

3 |

10 |

16.67 |

15 |

25.00 |

|

|

4 |

4 |

6.67 |

4 |

6.67 |

|

|

>5 |

2 |

3.33 |

3 |

4.99 |

|

Note. a = Pearson chi-square test; b = Fisher’s exact test.

Effectiveness of the emergency illness prevention program on caregivers’ knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations

Both within-group and between-group analyses were conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the emergency illness prevention program among caregivers of older adults in Northern Thailand.

Within-Group Analysis. As shown in Table 3, paired t-tests revealed that the experimental group demonstrated statistically significant improvements in knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations from pre-intervention to post-intervention (all P<0.001). In contrast, no significant changes were observed in the control group across these outcomes (all P>0.05).

Table 3. Comparison of pre- and post-intervention mean scores of caregivers’ knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations within groups (paired t-test).

|

Variables |

Mean (SD) |

t |

P-value |

|

|

Baseline (Pre-intervention) |

Week 10 (Pre-intervention) |

|||

|

Control group (n=60) Knowledge Self-Efficacy Outcome Expectations |

7.51 (1.94) 47.73 (8.37) 49.83 (8.45) |

7.81 (1.79) 47.80 (8.34) 50.92 (7.40) |

-1.207 -4.253 -1.466 |

0.232 0.323 0.148 |

|

Experimental group (n=60) Knowledge Self-Efficacy Outcome Expectations |

7.41 (2.24) 48.75 (9.74) 47.82 (6.71) |

12.45 (0.98) 82.27 (6.49) 67.12 (5.28) |

-18.364 -28.932 -23.941 |

<0.001*** <0.001*** <0.001*** |

Note. P<0.05*, P<0.01**, P<0.001***

Between-Group Analysis. Independent t-test results are presented in Table 4. At pre-intervention, there were no significant differences between the experimental and control groups in knowledge, self-efficacy, or outcome expectations (all P>0.05). However, at post-intervention, the experimental group achieved significantly higher scores than the control group in all three outcomes (all P<0.001).

These findings provide strong evidence that the program was effective in enhancing caregivers’ knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations.

Table 4. Comparison of mean scores of caregivers’ knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations between experimental and control groups (independent t-test)

|

Variables |

Mean (SD) |

t |

P-value |

|

|

Control group (n=60) |

Experimental group (n=60) |

|||

|

Knowledge Baseline (Pre-intervention) Week 10 (Post-intervention) |

7.51 (1.94) 7.81 (1.79) |

7.41 (2.24) 12.45 (0.98) |

-0.261 17.511 |

0.794 <0.001** |

|

Self-Efficacy Baseline (Pre-intervention) Week 10 (Post-intervention) |

47.73 (8.37) 47.80 (8.34) |

48.75 (9.74) 82.27 (6.49) |

0.613 25.255 |

0.541 <0.001** |

|

Outcome Expectations Baseline (Pre-intervention) Week 10 (Post-intervention) |

49.83 (8.45) 50.92 (7.40) |

47.82 (6.71) 67.12 (5.28) |

-1.447 13.805 |

0.151 <0.001** |

Note. P<0.05*, P<0.01**, P<0.001***

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study indicate that the participatory emergency illness prevention program significantly enhanced caregivers’ knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations in providing care for older adults. These results are supported by the statistical analyses, which demonstrated that the experimental group showed significant improvements in all three outcomes from pre- to post-intervention, whereas the control group did not (all P<0.001 vs. P>0.05). Moreover, between-group comparisons revealed no differences at baseline, but significantly higher post-intervention scores in the experimental group compared with the control group across all domains (all P<0.001). These findings provide strong evidence of the program’s effectiveness, aligning with prior studies reporting that structured, participatory training can improve caregivers’ capacity to recognize and respond to emergency situations (Liu et al., 2021; Kaewsriwong et al., 2023; Pongtriang et al., 2024).

Although overall improvements were observed, prior studies have noted that certain knowledge domains—particularly the ability to recognize subtle early warning signs of emergency illness—may remain limited even after training (Pongtriang et al., 2024). Similarly, outcome expectations related to the long-term sustainability of caregiving and the perceived impact on older adults’ quality of life have demonstrated only limited improvement. Furthermore, evidence from Thai caregiver interventions suggests that emotional coping and stress management within self-efficacy are domains that often improve more gradually, requiring continuous reinforcement and peer support (Boonyathee et al., 2021).

To address these gaps, future implementations of the program could incorporate structured stress management modules, including guided mindfulness exercises, peer support groups, and periodic refresher sessions delivered by community health volunteers. Embedding booster sessions post-intervention may also help sustain program gains, as demonstrated in prior intervention studies that integrated follow-up reinforcement to consolidate self-efficacy over time (Pongtriang et al., 2024).

Overall, this study reinforces the value of participatory, scenario-based training programs for caregivers, particularly in under-resourced settings. Future research should explore the long-term sustainability of intervention effects, with specific attention to knowledge, emotional, and psychological domains, and examine the program’s generalizability across diverse community contexts.

RESEARCH LIMITATIONS

This study has some limitations. The geographic focus on Northern Thailand restricts generalizability, and the use of purposive sampling may introduce selection bias. The quasi-experimental design also limits the ability to establish strong causal inferences. In addition, caregiver behavior was not directly assessed, making it difficult to confirm whether knowledge and skills were applied in practice. Future research should address these issues through probability sampling, multi-site recruitment, behavioral outcome measures, and long-term follow-up.

CONCLUSION

The participatory emergency illness prevention program significantly improved caregivers’ knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations in caring for older adults. These findings highlight the value of community-based interventions tailored to caregivers’ needs, particularly among vulnerable populations with limited access to formal training. Implementing such programs can enhance caregiving quality and potentially reduce adverse outcomes in older adults.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Future studies should consider employing randomized controlled trials with larger and more diverse samples to enhance the generalizability of findings. Longitudinal follow-up is recommended to assess the sustainability of behavioral changes and knowledge retention over time. Importantly, future research should integrate behavioral outcome measures—such as direct observation of caregiving practices in simulated or real emergency situations—to capture whether improvements translate into observable competencies. Finally, evaluating the cultural relevance, cost-effectiveness, and scalability of such participatory programs will be essential to support integration into broader community health systems and inform health policy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to sincerely thank all caregivers who participated in this study for their valuable time and cooperation. Special appreciation is extended to the Faculty of Public Health, Chiang Mai University, for providing support and resources throughout the research process. We also acknowledge the assistance of the local community health centers and staff who facilitated data collection and intervention sessions. Their contributions were essential to the successful completion of this study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they hold no competing interests.

REFERENCES

Adelman, R.D., Tmanova, L.L., Delgado, D., Dion, S., and Lachs, M.S. 2014. Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA. 311(10): 1052-1060. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.304

Aung, M.N., Srinonprasert, V., Prasert, V., Kannawat, N., Rojpaisarnkit, K., Toh, N., and Anantanasuwong, T. 2022. Effectiveness of a community-integrated intermediary care (CIIC) service model in Thailand: A randomized controlled trial. Health Research Policy and Systems. 20(1): 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-022-00911-5

Bandura, A. 1997. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman.

Bevans, M.F. and Sternberg, E.M. 2012. Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. JAMA. 307(4): 398-403. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.29

Bloom, B.S. 1956. Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. Longmans, Green, New York.

Boonyathee, S., Seangpraw, K., Ong-Artborirak, P., Auttama, N., Tonchoy, P., Kantow, S., Bootsikeaw, S., Choowanthanapakorn, M., Panta, P., and Dokpuang, D. 2021. Effects of a social support family caregiver training program on changing blood pressure and lipid levels among elderly at risk of hypertension in a northern Thai community. PLoS One. 16(11): e0259697. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259697

Choi, H., Lee, Y., and Yu, H. 2024. Factors influencing caregiver burden among family caregivers of community-dwelling older adults with chronic diseases: A systematic review. Healthcare. 12(10): 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12101002

Cui, L., Sun, M., Wu, S., Zhao, Y., and Liang, H. 2024. Caregiver burden and its impact on quality of life among family caregivers of patients with cancer: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 24: 18321. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18321-3

Department of Older Persons. 2024. Situation of the Thai Older Persons 2023. Ministry of Social Development and Human Security.

Doungchan, N., Sinprasert, P., Throngthieng, W., Wanchai, A., Sutthilak, C., and Banlengchit, S. 2021. Stroke in older people and guidelines for strengthening caregivers. Journal of the Royal Thai Army Nurses. 22(1): 20-28.

Edemekong, P.F. 2023. Activities of daily living (ADLs). In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.G., and Buchner, A. 2007. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical Power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 39(2): 175-191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Kaewsriwong, S., Buaboon, N., Kummabutr, J., and Phoolphoklang, S. 2023. Knowledge, attitude, social support, and caring ability of family caregivers of chronic illness patients in a community. Nursing Journal of Chiang Mai University. 50(3): 84-98.

Liu, C., Chen, X., Huang, M., Xie, Q., Lin, L., Chen, S., and Shi, D. 2021. Effect of health belief model education on increasing cognition and self-care behaviour among elderly women with malignant gynaecological tumours in Fujian, China. Journal of Healthcare Engineering. 2021: 1904752. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/1904752

Lumjeaksuwan, M., Patcharasopit, S., Seksanpanit, C., Sritharo, N., Aeampuck, A., and Wittayachamnankul, B. 2021. The trend of emergency department visits among the elderly in Thailand. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health. 10(1): 25-28. https://doi.org/10.4103/WHO-SEAJPH.WHO-SEAJPH_67_21

National Institute for Emergency Medicine. 2024. Annual report 2023. Ministry of Public Health. https://www.niems.go.th/1/Ebook/Detail/19848?group=23

National Statistical Office. 2025. The 2024 survey of the older persons in Thailand. Ministry of Digital Economy and Society.

Northouse, L.L., Katapodi, M.C., Song, L., Zhang, L., and Mood, D.W. 2012. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 30(11): 1227-1234. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5798

Pleasant, M., Molinari, V., Dobbs, D., Meng, H., and Hyer, K. 2020. Effectiveness of online dementia caregivers training programs: A systematic review. Geriatric Nursing. 41(6): 921-935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.07.004

Pongtriang, P., Soontorn, T., Sumleepun, J., Chuson, N., and Songwathana, P. 2024. Effect of emergency scenario-based training program on knowledge, self-confidence, and competency of elderly caregiver volunteers in a rural Thai community: A quasi-experimental study. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery. 12(4): 267-277.

Pruksacholavit, P. 2025. Aging population and employment in Thailand: Towards inclusive legal reforms [Conference presentation slides]. Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training. https://www.jil.go.jp/english/events/seminar/20250326/documents/Thailand_PPT.pdf

Ruangritchankul, S., and Pramotesiri, P. 2024. Caregiver burden in caregivers of older persons. Royal Thai Army Medical Journal. 77(1): 57-64.

Sanpunya, T., Intayos, H., and Jarkthong, S. 2022. Effects of an empowerment program on caregivers of older adults undergoing hip fracture surgery, Phare Hospital. Journal of Nursing and Public Health Research. 3(1): 33-48.

Sathagathonthun, G., Chairat, R., and Nateeprasittipon, P. 2021. The development of elderly caring guideline for caregivers in Tamnak Tham Subdistrict, Nong Muang Khai, Phrae Province. NU Journal of Nursing and Health Sciences. 15(3): 81-97.

Suna, N., Miankerd, W., and Cheausuwantavee, T. 2025. Developing a policy model to support family caregivers of dependent older adults in Bangkok. Journal of Population and Social Studies. 33: 524-543. https://doi.org/10.25133/JPSSv332025.028

Thummakul, D., Chusri, O., and Kwanyuen, R. 2025. Developing a program to promote the ability of caregivers to care for the elderly with dementia. Journal of Health Science of Thailand. 34(3): 488-500.

Wright, R., Lowton, K., Hanson, B.R., and Grocott, P. 2021. Older adult and family caregiver preferences for emergency department based-palliative care: An experience-based co-design study. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances. 3: 100016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2020.100016

OPEN access freely available online

Natural and Life Sciences Communications

Chiang Mai University, Thailand. https://cmuj.cmu.ac.th

Rossarin Kaewta1, Waraporn Boonchieng2, *, Kannikar Intawong2, Noppcha Singweratham2, and Sunisa Chansaeng3

1 Public Health Program, Faculty of Public Health, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

2 Faculty of Public Health, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

3 Faculty of Public Health and Allied Health Sciences, Praboromarajchanok Institute, Ministry of Public Health, Sirindhorn College of Public Health Suphanburi, Suphanburi 72000, Thailand.

Corresponding author: Waraporn Boonchieng, E-mail: waraporn.b@cmu.ac.th

ORCID iD:

Waraporn Boonchieng: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4084-848X

Rossarin Kaewta: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-6842-9531

Kannikar Intawong: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2704-9595

Noppcha Singweratham: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4925-8497

Sunisa Chansaeng: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-8510-3998

Total Article Views

Editor: Decha Tamdee,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: June 4, 2025;

Revised: September 15, 2025;

Accepted: September 18, 2025;

Online First: October 1, 2025