Diversity and Diurnal Habitat Utilization Behavior of Birds at Blue Lake, Prince of Songkla University, Pattani Campus, Pattani, Thailand

Somsak Buatip, Sitthisak Jantarat, Areena Truenae, Nurasiyah Teemasa, Tanakorn Chantasuban, Supaporn Saengkaew*, and Supakan BuatipPublished Date : September 23, 2025

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2026.003

Journal Issues : Number 1, January-March 2026

Abstract This study examines the diurnal habitat utilization of birds at Blue Lake, Prince of Songkla University, Pattani Campus, Pattani, Thailand from November 2024 to February 2025. Surveys were conducted twice monthly from 06:00 h to 19:00 h, divided into seven time intervals. Data collection involved the use of 10×42 mm binoculars and a telescope to record species composition, abundance, and behavior. A total of 69 species from 32 families were recorded, with February and the 08:00–09:00 h interval showing the highest species richness (57 species). Ardeidae was the most represented family (11 species), and the Edible-nest Swiftlet (Aerodramus fuciphagus) was the most abundant species. The Shannon-Wiener diversity index (H') averaged 2.91, peaking in November (3.13) and during the 12:00–13:00 h interval (3.26). The evenness index (E') averaged 0.69, with the highest values similarly in November (0.80) and within 12:00–13:00 h (0.85). Thirty-three species were present in all months, while 26 species were detected throughout all time intervals. The bird community included 40 resident species, 22 winter visitors, 1 as a resident–winter visitor, 2 as breeding visitors, and 4 were not available. Species of conservation concern included Black-capped Kingfisher (Halcyon pileata) and Javan Myna (Acridotheres javanicus) (vulnerable), and Asian Golden Weaver (Ploceus hypoxanthus) (near threatened). Birds exhibited a bimodal pattern in foraging, flying, and resting behaviors. Foraging and flying peaked in the morning (08:00–09:00 h) and late afternoon, while resting was most frequent between 12:00–17:00 h. Hierarchical cluster analysis revealed four time-interval groups and nine bird assembled groups. Findings reveal temporal bird activity shifts, stressing habitat conservation to support avian diversity and protection.

Keywords: Bird diversity, Conservation, Diurnal behavior, Pattani Bay, Urban Wetland

Graphical Abstract:

Funding: This research was supported by the Research Subsidy for Pattani Campus Development, Fiscal Year 2025 (Project Code: SAT6703028S), Prince of Songkla University, Pattani Campus, Thailand.

Citation: Buatip, S., Jantarat, S., Truenae, A., Teemasa, N., Chantasuban, T., Saengkaew, S., and Buatip, S. 2026. Diversity and diurnal habitat utilization behavior of birds at blue lake, Prince of Songkla University, Pattani campus, Pattani, Thailand. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 25(1): e2026003.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, around 9,800 to 10,000 bird species have been recorded (Clements et al., 2024), while Thailand hosts more than 1,000 species (Bird Conservation Society of Thailand, 2022). accounting for approximately 10% of the world’s bird species. This makes Thailand as one of the most bird-diverse countries globally. Birds play a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance (Whelan et al., 2008) by aiding in pollination, seed dispersal, scavengers, predators, pest control and ecosystem engineers (Johnson et al., 2010; Graham et al., 2018; Chanthorn et al., 2019; Grilli et al., 2019; Maisey et al., 2021; Naniwadekar et al., 2021). Additionally, birds serve as important bioindicators of environmental quality and ecosystem health (Fernández et al., 2005; Piratelli et al., 2008; Chowdhury et al., 2014) due to their adaptability to various habitats. Studying bird activity is crucial for understanding various aspects of their life, including food availability, social structure, and environmental factors such as rainfall, temperature, humidity, and predation. The daily activity of birds is shaped by their individual needs and interactions with other organisms, along with ecological factors such as group size and foraging behavior. Additionally, research on habitat use and foraging ecology in wetland birds is essential for understanding how species within a habitat partition their resources (Asokans et al., 2010; Aissaoui et al., 2011; Lillywhite and Brischoux, 2012). Behavioral patterns of birds are frequently employed to assess the functional role of wetland habitats and the ecological benefits they offer to wetland species (Reinecke, 1981; Brennan et al., 2005). Examples of studies include those conducted in Ithaca, NY, USA (Bonter et al., 2013) and southern Ethiopia (Kassa et al., 2021).

Prince of Songkla University, Pattani Campus, is located in Rusamilae Subdistrict, Mueang District, Pattani Province. It represents an urban ecosystem along the Gulf of Thailand, situated on the left side of the Pattani River estuary, covering an area of approximately 1.54 square kilometers. The campus features mangroves and mudflats to the north, along with canals, ponds, abandoned shrimp farms, buildings, lawns, gardens, large trees, forested areas, and scattered shrublands. These diverse habitats attract a variety of bird species, including forest birds, waterbirds, raptors, and shorebirds, which utilize the campus for various activities such as foraging, nesting, raising chicks, and resting during migration (Buatip and Chantasuban, 2021). Blue Lake is a small wetland that has been developed from an abandoned shrimp pond within the campus to serve as a recreational, leisure, and exercise area. However, a study on bird diversity was conducted at the Pattani Campus in 2017-2018 (Buatip et al., 2022), but no data was collected on the temporal habitat utilization of birds throughout the day. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the diversity of birds utilizing Blue Lake at different times of the day. The findings will serve as baseline data to support campus administrators and the Division of Physical and Environmental Affairs in managing the green spaces, which provide critical habitats for birds. Additionally, the study will contribute to the development of an urban ecological learning center, using birds as an educational medium for students, university staff, and the public in the future alongside recreational activities. While bird diversity in Pattani Bay area has been studied, little is known about how birds use wetlands throughout the day. This study addresses that gap by examining daily patterns of species diversity, behavior, and the presence of conservation-priority species at Blue Lake.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Area

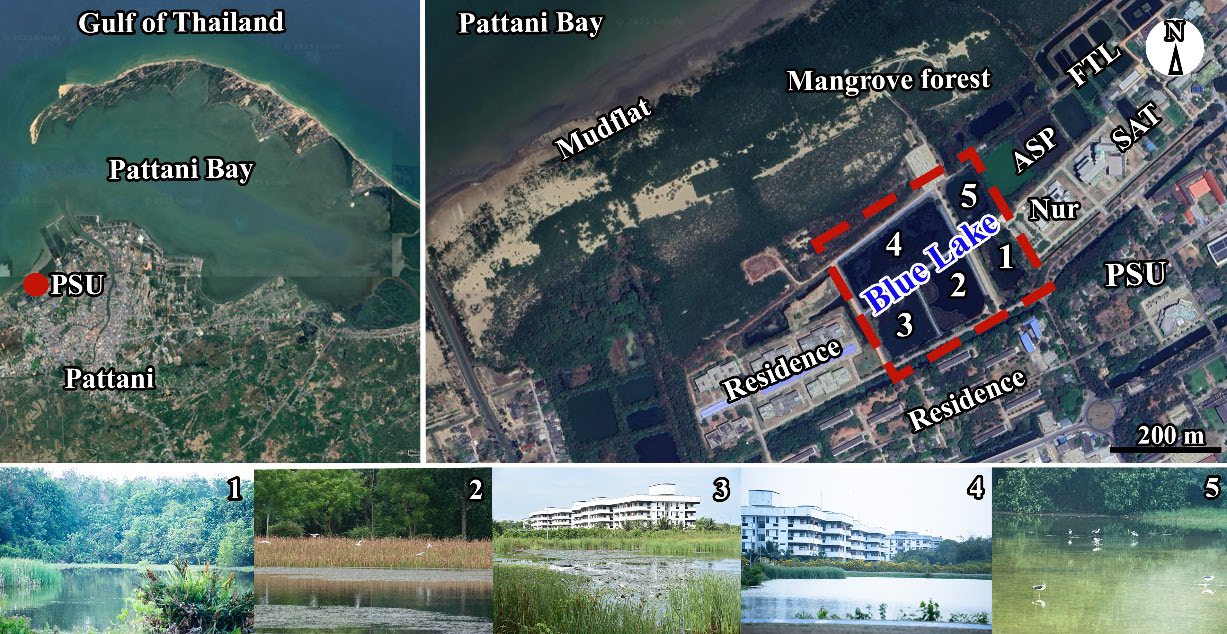

Prince of Songkla University, Pattani Campus, is in Moo 6, Rusamilae Subdistrict, Mueang District, Pattani Province, covering an area of approximately 1.54 square kilometers. It borders the Gulf of Thailand to the north, with a coastline of about 2 kilometers. Most of the green space consists of native tree species planted by the community when the university was relocated to Pattani. Blue Lake area has been developed for recreational purposes from an abandoned 5 shrimp ponds, covering an area of approximately 0.07 square kilometers. The area is characterized as a wetland, consisting of 5 abandoned shrimp ponds. Water levels range from 30 - 180 centimeters, and the water varies from slightly fresh to brackish, depending on the pond. Dominant aquatic plants include Typha angustifolia, Nymphaea spp., Najas marina, and Ruppia maritima. At the edges, the main plant species observed are Thespesia populnea, Leucaena leucocepphala and Excoecaria agallocha (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study area: Blue Lake, Prince of Songkla University (PSU), Pattani Campus; ASP: Abandoned shrimp pond; FTL: Fisheries Technology Lab; Nur: Faculty of Nursing; PSU: Prince of Songkla University, Pattani Campus; SAT: Faculty of Science and Technology, Map modified from Google Maps (2024).

Birds Count

Bird diversity was surveyed along predefined routes using a 1,000-meter line transect. Surveys were conducted within the time of 06:00 h to 18:00 h, divided into 7-time intervals: 06:00-07.00, 08:00-09.00, 10:00-11.00, 12:00-13.00, 14:00-15.00, 16:00-17.00, and 18:00-19.00. A 10×42 mm binoculars and a telescope were used to record the species and number of birds observed, with surveys conducted twice per month between November 2024-February 2025. Bird species were identified based on the field guide by Nabhitabhata et al. (2007) while the accuracy of scientific names was verified using eBird (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2025), and their conservation status was classified according to the IUCN Red List (version 2025-1) (IUCN, 2025).

Descriptions of bird behaviors in the study area

Foraging behavior refers to the strategies birds use to find and acquire food, varying by species and availability. These include pecking, where birds use their beaks to collect food from the ground or vegetation; hawking, which involves catching airborne insects while flying; and diving, where birds catch aquatic prey by plunging into water. Resting behavior involves activities that reduce movement and maintain the bird's condition. Birds may perch on branches or structures, stand/loaf on the ground or in shallow water, preen/bathe to maintain feathers, or sleep/roost alone or in groups, usually at night. And Fly-Through behavior occurs when birds pass through the study area without using its resources, such as during foraging flights (searching for food in flight) or commuting flights (traveling between roosting and feeding sites) (Fauzi et al., 2025).

Data analysis

- Species Diversity Index was calculated using the Shannon-Wiener Index formula (Shannon, 1949)

Where:

pi is the proportion of species i relative to the total population of birds

S is the total number of bird species

H′ is the species diversity index

- Evenness Index

Where:

H′ is the Shannon-Wiener species diversity index

S is the total number species of bird

E′ is the evenness index

Statistical analysis

This study collected ecological data on bird species, population numbers, data collection months, and time intervals (06:00, 08:00, 10:00, 12:00, 14:00, 16:00, 18:00) from November 2024 to February 2025. Two-way Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (THCA) was used to cluster data in both rows and columns, identifying similarities or differences in two-dimensional data. THCA analyzed bird species and their numbers using PC-ORD version 7.11 with the Group Average linkage method and Euclidean distance. Results were presented as a two-dimensional dendrogram, showing clustering based on spatial and temporal patterns and species similarity.

RESULTS

Birds’ diversity in Blue Lake

A total of 6,047 birds, 69 species and 32 families were observed and found within the research period. The highest species was recorded in February totaling 57 species (1,752 individuals, 28.97%). 08:00-09:00 h was recorded as the highest number of bird species totaling 57 species (1,256 individuals, 20.77%). The species diversity index (H') throughout the study period was 2.91, with the highest values recorded in November 2024 and between 12:00-13:00 h, at 3.13 and 3.26, respectively. The evenness index (E') for the entire period was 0.69, with the highest values observed in November 2024 and between 12:00-13:00 h, at 0.80 and 0.85, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. The accumulated number of species, total number of birds, H', and E' of birds observed at Blue Lake, Prince of Songkla University, Pattani Campus, from November 2024 to February 2025.

|

Time |

Bird Species |

Number of birds |

H' |

E' |

|

|

Total |

% |

||||

|

Sep. 2024 |

49 |

1,243 |

20.56 |

3.13 |

0.80 |

|

Dec. 2024 |

50 |

1,339 |

22.14 |

3.00 |

0.77 |

|

Jan. 2025 |

44 |

1,713 |

28.33 |

2.50 |

0.66 |

|

Feb. 2025 |

57 |

1,752 |

28.97 |

2.87 |

0.71 |

|

06.00-07.00 |

39 |

1,039 |

17.18 |

2.70 |

0.74 |

|

08.00-09.00 |

57 |

1,256 |

20.77 |

2.88 |

0.71 |

|

10.00-11.00 |

45 |

631 |

10.43 |

3.18 |

0.84 |

|

12.00-13.00 |

46 |

557 |

9.21 |

3.26 |

0.85 |

|

14.00-15.00 |

52 |

724 |

11.97 |

3.09 |

0.78 |

|

16.00-17.00 |

45 |

968 |

16.01 |

2.56 |

0.67 |

|

18.00-19.00 |

38 |

872 |

14.42 |

1.75 |

0.48 |

|

Blue Lake |

69 |

6,047 |

100 |

2.91 |

0.69 |

The family with the most bird species recorded is Ardeidae with 11 species. The top 5 most common bird species observed are Edible-nest Swiftlet (Aerodramus fuciphagus) 32.38% (1,958), Yellow-vented Bulbul (Pycnonotus goiavier) 7.74% (468), Yellow Bittern (Botaurus sinensis) 5.34% (323), Spotted Dove (Spilopelia chinensis) 4.58% (277) and Pink-necked Green-Pigeon (Treron vernans) 4.18% (253). The frequently found birds in every month of the survey totaled to 33 species in which 16 species of birds were observed only in a single month. The most frequent birds observed every time during the daily survey totaled 26 species and only 10 species were observed at a single time of the day (Table 2, Figure 2).

Based on the seasonal classification by Nabhitabhata et al. (2007), birds are categorized into 40 resident species. 22 Winter visitors, including the Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis), Common Greenshank (Tringa nebularia), Whiskered Tern (Chlidonias hybrida), Black Baza (Aviceda leuphotes), Japanese Sparrowhawk (Tachyspiza gularis), Purple Heron (Ardea purpurea), Grey Heron (Ardea cinerea), Chinese Pond-Heron (Ardeola bacchus), Brown Shrike (Lanius cristatus), Arctic Warbler (Phylloscopus borealis), etc. Black-winged Stilt (Himantopus himantopus) is both a resident-winter visitor, while the Blue-tailed Bee-eater (Merops philippinus) is a resident-breeding visitor. Oriental Pratincole (Glareola maldivarum) is a breeding visitor. Four species, Oriental Darter (Anhinga melanogaster), Asian Openbill (Anastomus oscitans), Asian Golden Weaver (Ploceus hypoxanthus), and Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) did not exhibit any specific seasonal status in Pattani. According to the conservation status from the IUCN (2025), 2 bird species were classified as vulnerable namely Javan Myna (Acridotheres javanicus) and Black-capped Kingfisher (Halcyon pileata). Asian Golden Weaver (Ploceus hypoxanthus) was categorized as near threatened (Table 2, Figure 2)

Figure 2. Top 5 avian species by abundance and conservation concerns: focus on vulnerable and near threatened taxa; A: Edible-nest Swiftlet (Aerodramus fuciphagus); B: Yellow-vented Bulbul (Pycnonotus goiavier); C: Yellow Bittern (Botaurus sinensis); D: Spotted Dove (Spilopelia chinensis); E: Pink-necked Green-Pigeon (Treron vernans); F: Javan Myna (Acridotheres javanicus); G: Black-capped Kingfisher (Halcyon pileata); H: Asian Golden Weaver (Ploceus hypoxanthus)

Table 2. Species, number of birds on month and time between a day, Conservation status following IUCN red list and Seasonal status of birds in the Blue Lake area of Prince of Songkla University, Pattani Campus (Nov. 2024-Feb. 2025).

|

Family/Species |

Common name |

Total |

Month |

Time between a day |

Conservation status IUCN red list |

Seasonal status |

|||||||||

|

Nov 2024 |

Dec 2024 |

Jan 2025 |

Feb 2025 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|||||

|

Anatidae Dendrocygna javanica |

Lesser Whistling Duck |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Alcedinidae Alcedo atthis |

Common Kingfisher |

5 |

4 |

- |

- |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

LC |

W |

|

Halcyon pileata |

Black-capped Kingfisher |

3 |

- |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

VU |

W |

|

Pelargopsis capensis |

Stork-billed Kingfisher |

9 |

3 |

5 |

- |

1 |

- |

4 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Halcyon smyrnensis |

White-throated Kingfisher |

27 |

8 |

12 |

2 |

5 |

5 |

8 |

6 |

- |

3 |

4 |

1 |

LC |

R |

|

Todiramphus chloris |

Collared Kingfisher |

7 |

- |

2 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

LC |

R |

|

Meropidae Merops philippinus |

Blue-tailed Bee-eater |

205 |

42 |

48 |

64 |

51 |

4 |

43 |

34 |

35 |

52 |

37 |

- |

LC |

R-B |

|

Cuculidae Eudynamys scolopaceus |

Asian Koel |

40 |

14 |

12 |

8 |

6 |

4 |

8 |

2 |

6 |

4 |

8 |

8 |

LC |

R |

|

Phaenicophaeus tristis |

Green-billed Malkoha |

2 |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Centropus sinensis |

Greater Coucal |

2 |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Apodidae Aerodramus fuciphagus |

Edible-nest Swiftlet |

1,958 |

234 |

278 |

740 |

706 |

365 |

431 |

119 |

30 |

135 |

323 |

555 |

LC |

R |

|

Columbidae Geopelia striata |

Zebra Dove |

34 |

5 |

9 |

7 |

13 |

1 |

2 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

1 |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Spilopelia chinensis |

Spotted Dove |

277 |

38 |

103 |

92 |

44 |

12 |

29 |

59 |

65 |

61 |

48 |

3 |

LC |

R |

|

Treron vernans |

Pink-necked Green-Pigeon |

253 |

65 |

126 |

33 |

29 |

30 |

90 |

14 |

28 |

30 |

56 |

5 |

LC |

R |

|

Rallidae Amaurornis phoenicurus |

White-breasted Waterhen |

112 |

37 |

24 |

22 |

29 |

23 |

17 |

14 |

14 |

24 |

11 |

9 |

LC |

R |

|

Poliolimnas cinereus |

White-browed Crake |

100 |

1 |

17 |

46 |

36 |

12 |

18 |

19 |

10 |

13 |

24 |

4 |

LC |

R |

|

Gallinula chloropus |

Eurasian Moorhen |

38 |

- |

- |

16 |

22 |

8 |

7 |

7 |

4 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

LC |

W |

|

Gallicrex cinerea |

Watercock |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Porphyrio poliocephalus |

Grey-headed Swamphen |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Scolopacidae Actitis hypoleucos |

Common Sandpiper |

5 |

1 |

3 |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

3 |

1 |

- |

- |

LC |

W |

|

Tringa nebularia |

Common Greenshank |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

LC |

W |

|

Recurvirostridae Himantopus himantopus |

Black-winged Stilt |

16 |

13 |

2 |

1 |

- |

2 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

6 |

- |

- |

LC |

R-W |

|

Glareolidae Glareola maldivarum |

Oriental Pratincole |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

LC |

B |

|

Laridae Chlidonias hybrida |

Whiskered Tern |

9 |

- |

2 |

2 |

5 |

1 |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

2 |

LC |

W |

|

Accipitridae Aviceda leuphotes |

Black Baza |

4 |

4 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

LC |

W |

|

Haliastur indus |

Brahminy Kite |

12 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

- |

- |

4 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

LC |

R |

|

Icthyophaga leucogaster |

White-bellied Sea-Eagle |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Tachyspiza gularis |

Japanese Sparrowhawk |

7 |

4 |

2 |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

3 |

2 |

LC |

W |

|

Podicipedidae Tachybaptus ruficollis |

Little Grebe |

150 |

46 |

34 |

28 |

42 |

20 |

21 |

19 |

28 |

23 |

16 |

23 |

LC |

R |

|

Anhingidae Anhinga melanogaster |

Oriental Darter |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

LC |

NA |

|

Phalacrocoracidae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Microcarbo niger |

Little Cormorant |

235 |

110 |

53 |

31 |

41 |

75 |

37 |

28 |

20 |

14 |

43 |

18 |

LC |

W |

|

Ardeidae Ardea purpurea |

Purple Heron |

46 |

9 |

9 |

18 |

10 |

6 |

6 |

12 |

5 |

12 |

4 |

1 |

LC |

W |

|

Ardea cinerea |

Grey Heron |

41 |

17 |

6 |

12 |

6 |

11 |

8 |

7 |

7 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

LC |

W |

|

Ardea coromanda |

Eastern Cattle-Egret |

3 |

- |

- |

2 |

1 |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

LC |

W |

|

Ardea intermedia |

Intermediate Egret |

114 |

14 |

21 |

62 |

17 |

18 |

9 |

9 |

13 |

18 |

10 |

37 |

LC |

W |

|

Ardea alba |

Great Egret |

87 |

24 |

11 |

13 |

39 |

37 |

12 |

7 |

13 |

4 |

9 |

5 |

LC |

W |

|

Egretta garzetta |

Little Egret |

120 |

25 |

20 |

29 |

46 |

46 |

12 |

7 |

7 |

9 |

9 |

30 |

LC |

R-B |

|

Ardeola bacchus |

Chinese Pond-Heron |

120 |

23 |

39 |

37 |

21 |

30 |

14 |

10 |

7 |

11 |

10 |

38 |

LC |

W |

|

Butorides striata |

Striated Heron |

7 |

2 |

- |

3 |

2 |

- |

4 |

- |

1 |

2 |

- |

- |

LC |

W |

|

Nycticorax nycticorax |

Black-crowned Night Heron |

8 |

1 |

- |

4 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

- |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

LC |

NA |

|

Botaurus cinnamomeus |

Cinnamon Bittern |

5 |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

3 |

- |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Botaurus sinensis |

Yellow Bittern |

323 |

49 |

102 |

96 |

76 |

52 |

52 |

52 |

57 |

49 |

37 |

24 |

LC |

R |

|

Ciconiidae Anastomus oscitans |

Asian Openbill |

41 |

1 |

3 |

15 |

22 |

10 |

16 |

11 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

LC |

NA |

|

Laniidae Lanius cristatus |

Brown Shrike |

21 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

7 |

- |

7 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

- |

LC |

W |

|

Corvidae Crypsirina temia |

Racket-tailed Treepie |

6 |

3 |

- |

2 |

1 |

- |

2 |

- |

2 |

- |

2 |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Corvus macrorhynchos |

Large-billed Crow |

7 |

3 |

3 |

- |

1 |

3 |

2 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Rhipiduridae Rhipidura javanica |

Malaysian Pied-Fantail |

44 |

15 |

20 |

2 |

7 |

7 |

13 |

4 |

7 |

4 |

6 |

3 |

LC |

R |

|

Aegithinidae Aegithina tiphia |

Common Iora |

47 |

21 |

7 |

11 |

8 |

- |

14 |

8 |

13 |

4 |

7 |

1 |

LC |

R |

|

Muscicapidae Copsychus saularis |

Oriental Magpie-robin |

56 |

2 |

17 |

17 |

20 |

6 |

26 |

4 |

7 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

LC |

R |

|

Sturnidae Acridotheres javanicus |

Javan Myna |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

VU |

W |

|

Acridotheres tristis |

Common Myna |

141 |

36 |

59 |

22 |

24 |

21 |

34 |

15 |

11 |

20 |

31 |

9 |

LC |

R |

|

Acridotheres grandis |

Great Myna |

38 |

24 |

10 |

- |

4 |

- |

12 |

10 |

10 |

6 |

- |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Hirundinidae Hirundo tahitica |

Tahiti Swallow |

80 |

36 |

6 |

15 |

23 |

28 |

11 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

19 |

8 |

LC |

R |

|

Pycnonotidae Pycnonotus goiavier |

Yellow-vented Bulbul |

468 |

155 |

106 |

95 |

112 |

46 |

92 |

23 |

33 |

83 |

166 |

25 |

LC |

R |

|

Cisticolidae Prinia flaviventris |

Yellow-bellied Prinia |

227 |

34 |

58 |

70 |

65 |

59 |

42 |

23 |

40 |

20 |

23 |

20 |

LC |

R |

|

Cisticola juncidis |

Zitting Cisticola |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Orthotomus sutorius |

Common Tailorbird |

5 |

- |

1 |

1 |

3 |

- |

3 |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Orthotomus ruficeps |

Ashy Tailorbird |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Acrocephalidae Acrocephalus bistrigiceps |

Black-browed Reed Warbler |

77 |

3 |

18 |

13 |

43 |

16 |

23 |

11 |

6 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

LC |

W |

|

Acrocephalus orientalis |

Oriental Reed Warbler |

17 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

11 |

1 |

11 |

- |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

LC |

W |

|

Phylloscopidae Phylloscopus borealis |

Arctic Warbler |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

LC |

W |

|

Acanthizidae Gerygone sulphurea |

Golden-bellied Gerygone |

2 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Dicaeidae Dicaeum cruentatum |

Scarlet-backed Flowerpecker |

81 |

6 |

30 |

31 |

14 |

34 |

12 |

12 |

11 |

8 |

3 |

1 |

LC |

R |

|

Nectariniidae Anthreptes malacensis |

Brown-throated Sunbird |

6 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

- |

2 |

1 |

- |

2 |

1 |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Cinnyris jugularis |

Olive-backed Sunbird |

140 |

70 |

9 |

21 |

40 |

13 |

31 |

28 |

22 |

24 |

20 |

2 |

LC |

R |

|

Ploceidae Ploceus hypoxanthus |

Asian Golden Weaver |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

NT |

NA |

|

Estrildidae Lonchura striata |

White-rumped Munia |

5 |

- |

- |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

LC |

R |

|

Lonchura punctulata |

Scaly-breasted Munia |

71 |

19 |

34 |

- |

18 |

11 |

10 |

12 |

8 |

18 |

4 |

8 |

LC |

R |

|

Lonchura atricapilla |

Chestnut Munia |

66 |

2 |

- |

14 |

50 |

16 |

31 |

9 |

4 |

0 |

4 |

2 |

LC |

R |

|

Note: Time between a day; 1: 06.00-07.00; 2: 08.00-09.00; 3: 10.00-11.00; 4: 12.00-13.00; 5: 14.00-15.00; 6: 16.00-17.00; 7: 18.00-19.00 Conservation status IUCN Red List; LC: Least Concern; NT: Near Threatened; VU: Vulnerable Seasonal status; B: Breeding visitor; R: Resident; R-B: Resident-Breeding visitor; R-W: Resident-Winter visitor; W: Winter visitor; NA: Not Available |

|||||||||||||||

The diurnal habitat utilization behavior of birds in the study area.

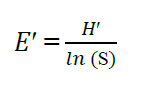

This research found that bird foraging behavior commenced at dawn (06:00 h), involving 13.14% (35 species) of the total observed species. Activity peaked at 08:00–09:00 h, accounting for 13.37% (51 species). Subsequently, the number of foraging species declined before increasing again in the late afternoon (16:00–17:00 h), with a second peak observed at 18:00–19:00 h, comprising 10.84% (24 species). Resting behavior was most frequently observed during 08:00–09:00 h and 12:00–17:00 h, with the highest occurrence recorded between 16:00–17:00 h, accounting for 3.75% (29 species) of the total. Flying behavior was most prominent during the early morning hours (06:00–09:00 h), gradually declining thereafter, before increasing again in the afternoon (14:00–17:00 h). The highest morning activity was observed at 08:00–09:00 h, accounting for 4.56% (30 species), while the peak in the afternoon occurred at 16:00–17:00 h, representing 3.57% (24 species) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Birds’ behavior (foraging, resting and flying) in Blue Lake, categorized by time periods (06:00-19:00 h) between November 2024-February 2025; A: total species; B: percentage of behavior of total birds.

DISCUSSION

Birds’ diversity in Blue Lake

Blue Lake of PSU Pattani is considered as a small open wetland with aquatic vegetation and year-round water retention. It is located along Pattani bay’s coast, surrounded by diverse ecosystems, including mangroves, mudflats, salt marshes, salt pans, active and abandoned shrimp ponds, rice fields, canals, and wastewater ponds. Hence, the proximity of these habitats facilitates bird movement, providing essential foraging, nesting, breeding, and stopover sites for resident and migratory birds (Ruttanadakul and Ardsungnoen, 1985; Ruttanadakul and Chaipakdee, 1987; Buatip et al., 2013, 2014; Buatip and Chantasuban, 2021; Buatip et al., 2022). This study recorded 69 bird species, including 29 waterbirds (42.03%), exceeding the discovery by Buatip et al. (2022), who recorded 65 species (20 waterbirds, 30.76%) at Blue Lake from March 2017 to February 2018. The most frequently observed species was the Edible-nest Swiftlet (Aerodramus fuciphagus), likely due to a model swiftlet house established in the university since 2010 (Lueangthuwapranit, 2019).

Compared to the findings of Buatip et al. (2022), this study recorded 20 additional bird species, of which seven were newly documented within the entire university area: Eurasian Moorhen (Gallinula chloropus), Grey-headed Swamphen (Porphyrio poliocephalus), White-bellied Sea-Eagle (Icthyophaga leucogaster), Oriental Darter (Anhinga melanogaster), Javan Myna (Acridotheres javanicus), Zitting Cisticola (Cisticola juncidis), and Asian Golden Weaver (Ploceus hypoxanthus). Notably, three of these species had never been previously reported in Pattani Bay. Although Javan Myna (Acridotheres javanicus) was observed only once during the survey at Blue Lake, it is known to occur in larger numbers in other parts of the campus. Asian Golden Weaver (Ploceus hypoxanthus) was first recorded nesting in 2024, while Zitting Cisticola (Cisticola juncidis) sighted once in January 2025. These findings clearly align with previous studies (Sa-Ar et al., 2018; Buatip and Chantasuban, 2021; Buatip et al., 2022), which reported a steady influx of new species into Pattani bay. Meanwhile, 16 species from the earlier study were absent from this survey but still present in other university areas, most likely due to differences in survey duration, seasonal coverage, and methodology. The 2017-2018 study surveyed once daily at 06:00–11:00 h (Buatip et al., 2022), whereas this study used a different approach.

The area has transformed into a wetland ecosystem. Aquatic plants, native and newly planted trees, enrich biodiversity exist along the banks. Blue Lake now provides crucial ecological services, supporting various animal groups. Birds, as apex consumers, help maintain balance. Numerous fish species inhabit the pond, including Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), Java tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus), Common Snakehead (Channa striata), and Three-spot gourami (Trichopodus trichopterus). Meanwhile, the surrounding terrestrial environment supports various insects, amphibians, and reptiles. In addition, aerial insects are abundant in the area, serving as prey for insectivorous birds. Blue Lake has become a key habitat attracting diverse bird species with varying diets, like findings from the Chaipattana Foundation’s project at Laem Phak Bia, Phetchaburi (The Chaipattana Foundation, 2008). Granivores include Zebra Dove (Geopelia striata), Spotted Dove (Spilopelia chinensis), and Munias. Nectarivores include Scarlet-backed Flowerpecker (Dicaeum cruentatum) and Sunbirds. Insectivores range from Green-billed Malkoha (Phaenicophaeus tristis) and Common Iora (Aegithina tiphia) to various warblers. Aerial insectivores include Blue-tailed Bee-eater (Merops philippinus), Swiftlets, and Swallows. Piscivores such as Oriental Darter (Anhinga melanogaster), Herons, and Egrets coexist with small aquatic/benthic invertebrate feeders like Lesser Whistling Duck (Dendrocygna javanica) and Common Sandpiper (Actitis hypoleucos). Molluscivores include the Asian Openbill (Anastomus oscitans), while predators like Japanese Sparrowhawk (Tachyspiza gularis) and Brown Shrike (Lanius cristatus), scavengers like Large-billed Crow (Corvus macrorhynchos), Greater Coucal (Centropus sinensis) and Brahminy Kite (Haliastur indus), etc., contribute to ecosystem balance.

In addition, the location of Blue Lake lies along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway of migratory birds, near Pattani Bay’s coastline (Ruttanadakul and Ardsungnoen, 1985; Ruttanadakul and Chaipakdee, 1987; Buatip and Chantasuban, 2021), similar to coastal areas from Samut Sakhon to Phetchaburi (Sripanomyom et al., 2011). It is also linked to mangroves and mudflats, which have a higher benthic biomass than other parts of the Malay Peninsula (Swennen and Marteijn, 1985, 1988). Pattani Bay is also one of the three most important mudflat areas in Southeast Asia. (Deppe, 1999). During the survey, 25 migratory bird species were recorded, including members of Scolopacidae, Recurvirostridae, Ardeidae, Laniidae, Accipitridae, and Acrocephalidae (Table 2).

Additionally, the area provides ecosystem services to certain groups of migratory birds, such as Oriental Pratincole (Glareola maldivarum), which is a breeding visitor distributed across East Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia. (Tobgay, 2017). While it does not nest at Blue Lake, it uses nearby mudflats near Ban Bang Pla Mo, about 3.5 kilometers west of the university. Chantasuban et al. (2024) reported its breeding grounds in the Phu Lan Khwai peat swamp, 38 kilometers south in Thung Yang Daeng District, Pattani. The Blue-tailed Bee-eater (Merops philippinus) is a resident-breeding visitor distributed in Southeast Asia and breeding in South Asia as well as Southeast Asia (Kasambe, 2005; Yuan et al., 2006; Patra and Chowdhury, 2017; IUCN, 2025). Although no nesting has been recorded at Blue Lake, breeding has been documented near the 912 Radio Station in Narathiwat (82 km east) and the Phu Lan Khwai peat swamp in Thung Yang Daeng, Pattani (38 km south) (Chantasuban et al., 2024). And Black-winged Stilt (Himantopus himantopus), a resident-winter visitor, breeds in Pond 5 during the dry season when the pond is cracked. Breeding has also been observed in nearby mudflats, salt marsh, and salt pan. And the other species that nest and rear young in the area include the Little Grebe (Tachybaptus ruficollis), which builds floating nests with aquatic plants, the Asian Golden Weaver (Ploceus hypoxanthus) and Chestnut Munia (Lonchura atricapilla), which weave nests in sedge thickets, and the White-breasted Waterhen (Amaurornis phoenicus), Yellow-vented Bulbul (Pycnonotus goiavier), and Yellow-bellied Prinia (Prinia flaviventris).

According to the IUCN Red List, species listed as vulnerable include the Javan Myna (Acridotheres javanicus) and Black-capped Kingfisher (Halcyon pileata). The Javan Myna (Acridotheres javanicus), native to Java and Bali, has spread to the southern Malay Peninsula, Singapore, Sumatra, Borneo, Christmas Island, Japan, Taiwan, and Thailand (Tasirin and Fitzsimon, 2014; Chantasuban et al., 2024; IUCN, 2025). The Black-capped Kingfisher (Halcyon pileata) is often found in mangrove forests and coastal wetlands, and migrates across Thailand, South and Southeast Asia, and parts of China and Korea in summer. Its nesting range extends to the Mongolian Autonomous Region, with occasional sightings in Russia and Japan (Nabhitabhata et al., 2007; Brazil, 2009; Woodall and Kirwan, 2013; Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2025). And Asian Golden Weaver (Ploceus hypoxanthus), listed as near threatened, shares this status with migratory shorebirds in Pattani Bay, such as the Curlew Sandpiper (Calidris ferruginea), Red-necked Stint (Calidris ruficollis), Red Knot (Calidris canutus), and Malaysian Plover (Anarhynchus peronii) (Buatip and Chantasuban, 2021). It inhabits flooded agricultural areas and natural wetlands. In Thailand, it is a resident species in the central, northern, and northeastern regions, and is also distributed in southeast Asia (Nabhitabhata et al., 2007; Razaq et al., 2023; Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2025).

The diurnal habitat utilization behavior of birds in the study area.

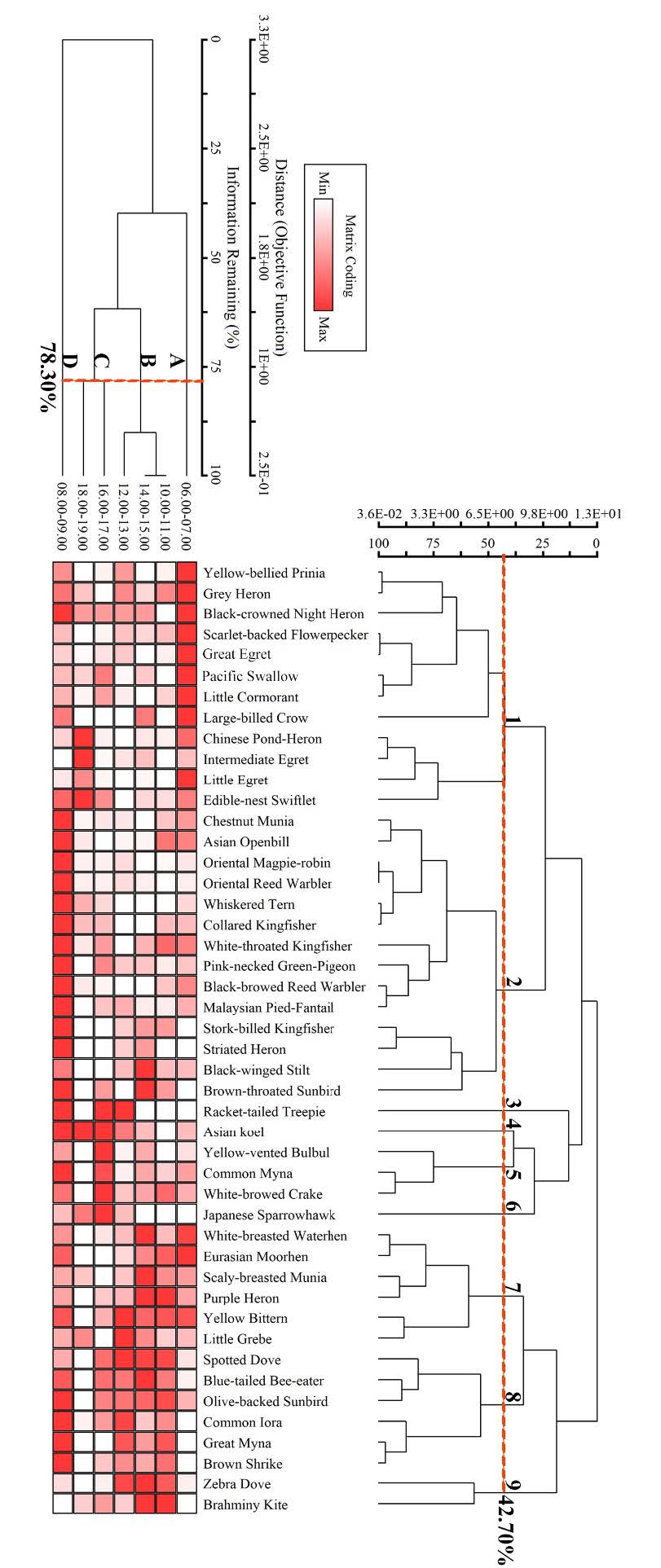

The analysis of the relationship between time periods and bird species occurrence at Blue Lake, based on species with more than 5 individuals, included 46 species, accounting for over 99% of the total bird count. A two-way Hierarchical Cluster Analysis using the Group Average method and Euclidean similarity in PC-ORD 7.11 software revealed 4 time periods (A, B, C, and D) at a similarity level of 78.30%. Additionally, 9 bird species clusters were identified at a similarity level of 42.70% (Figure 4). The details are as follows:

During the 06:00-07:00 h period (Group A), bird activity was primarily observed in Group 1, with nine prominent species, along with three species from Group 7. Of these, nine were waterbirds, indicating that these species begin foraging early in the morning. The most notable species included Little Egret (Egretta garzetta), Great Egret (Ardea alba), Grey Heron (Ardea cinerea), Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax), Yellow Bittern (Botaurus sinensis), Eurasian Moorhen (Gallinula chloropus), White-breasted Waterhen (Amaurornis phoenicus), Little Cormorant (Microcarbo niger), Large-billed Crow (Corvus macrorhynchos), Tahiti Swallow (Hirundo tahitica), Scarlet-backed Flowerpecker (Dicaeum cruentatum), and Yellow-bellied Prinia (Prinia flaviventris).

During the 10:00-15:00 h period (Group B), bird species from Groups 2, 3, 7, 8, and 9 were observed, totaling 15 species. Among them, 12 were considered prominent, including Spotted Dove (Spilopelia chinensis), Zebra Dove (Geopelia striata), Black-winged Stilt (Himantopus himantopus), Little Grebe (Tachybaptus ruficollis), Purple Heron (Ardea purpurea), White-breasted Waterhen (Amaurornis phoenicus), Brahminy Kite (Haliastur indus), Racket-tailed Treepie (Crypsirina temia), Common Iora (Aegithina tiphia), Blue-tailed Bee-eater (Merops philippinus), Brown-throated Sunbird (Anthreptes malacensis), and Scaly-breasted Munia (Lonchura punctulata).

During the 16:00-19:00 h period (Group C), birds from Groups 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6 were observed, totaling 9 species. The most prominent species recorded during this time included Asian Koel (Eudynamys scolopaceus), Intermediate Egret (Ardea intermedia), Chinese Pond-Heron (Ardeola bacchus), White-browed Crake (Poliolimnas cinereus), Japanese Sparrowhawk (Tachyspiza gularis), Edible-nest Swiftlet (Aerodramus fuciphagus), Yellow-vented Bulbul (Pycnonotus goiavier), Common Myna (Acridotheres tristis), and Racket-tailed Treepie (Crypsirina temia).

During the 08:00-09:00 h period (Group D), almost all bird groups were recorded, except for Group 9. This period marked the peak of avian activity, with up to 44 species observed. Notably were only the Intermediate Egret (Ardea intermedia) and the Brahminy Kite (Haliastur indus). Twenty-one species were especially prominent during this time, including Pink-necked Green-Pigeon (Treron vernans), Asian Koel (Eudynamys scolopaceus), White-throated Kingfisher (Halcyon smyrnensis), Collared Kingfisher (Todiramphus chloris), Stork-billed Kingfisher (Pelargopsis capensis), Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax), Striated Heron (Butorides striata), Asian Openbill (Anastomus oscitans), Whiskered Tern (Chlidonias hybrida), Common Myna (Acridotheres tristis), Great Myna (Acridotheres grandis), Oriental Magpie-robin (Copsychus saularis), Malaysian Pied Fantail (Rhipidura javanica), Racket-tailed Treepie (Crypsirina temia), Common Iora (Aegithina tiphia), Brown Shrike (Lanius cristatus), Oriental Reed Warbler (Acrocephalus orientalis), Black-browed Reed Warbler (Acrocephalus bistrigiceps), Brown-throated Sunbird (Anthreptes malacensis), Olive-backed Sunbird (Cinnyris jugularis), and Chestnut Munia (Lonchura atricapilla). Feeding and resting were the most frequently observed behaviors during this period, along with the highest rate of movement between foraging sites.

Figure 4. Two-way Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (THCA) was used to analyze bird species and their abundance in the Blue Lake area of Prince of Songkla University, Pattani Campus, identifying 46 species, which accounted for more than 99% of the total bird population

Birds typically exhibit a bimodal foraging pattern, with two distinct peaks. The first peak occurs in the morning (06:00-09:00 h), when birds replenish energy reserves after an overnight fast, reducing the risk of starvation. During the midday hours, birds rest, minimize movement, and seek shelter in dense vegetation to avoid heat stress. The second peak happens between 16:00-19:00 h, as birds gather energy to sustain themselves overnight. Similar patterns of foraging behavior have been observed in species such as the Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus), Tufted Titmouse (Baeolophus bicolor), White-breasted Nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis), and House Finch (Haemorhous mexicanus) in Ithaca, NY, USA, where they forage before sunrise and reduce activity by sunset (Bonter et al., 2013). In Southern Ethiopia, the Egyptian Goose (Alopochen aegyptiaca) exhibited peak foraging activity during the morning (07:00-09:00 h) and afternoon (16:00–18:00 h) hours, in both the wet and dry seasons (Kassa et al., 2021). Habitat selection in birds is primarily driven by food availability and the characteristics of foraging areas. The abundance and distribution of food, as well as the diversity of vegetation, provide varied and reliable food sources. Leaf litter is also critical for sustaining arthropod communities, which serve as an essential food source for many bird species (Strong and Sherry, 2000; Fayt, 2003; Díaz, 2006; Watson and Herring, 2012; Okore and Amadi, 2016).

This study provides essential baseline data for bird diversity and daily activity patterns in an urban wetland. The findings highlight Blue Lake's role as a habitat for both residents and migratory birds, including vulnerable species. Such information supports habitat management planning, minimizes human disturbance during peak activity periods, and promotes the integration of bird-friendly practices into urban green space development.

CONCLUSION

The Blue Lake at Prince of Songkla University, Pattani Campus, is a small wetland (0.07 square kilometers) developed from an abandoned pond for recreational use. Bird surveys from November 2024 to February 2025 recorded 69 species from 32 families, with the highest species richness observed in February (57 species, 1,752 individuals, 28.97%). The peak bird diversity was during the 08:00–09:00 h period (57 species, 1,256 individuals, 20.77%). The Ardeidae family was the most diverse, with 11 species. The most abundant species were the Edible-nest Swiftlet (Aerodramus fuciphagus) (32.38%), Yellow-vented Bulbul (Pycnonotus goiavier) (7.74%), and Yellow Bittern (Botaurus sinensis) (5.34%). Sixteen species were recorded once, while 26 were present throughout the day. Of these species, 22 were classified as winter visitors, 1 as a resident–winter visitor, 2 as breeding visitors, and 4 were not available. The Black-capped Kingfisher (Halcyon pileata) and Javan Myna (Acridotheres javanicus) are vulnerable species, and the Asian Golden Weaver (Ploceus hypoxanthus) is near threatened. The Diversity Index (H') was 2.91, and the Evenness Index (E') was 0.69, with peak values in November 2024 and 12:00-13:00 h. The observed bird community exhibited clear bimodal patterns in foraging, flying, and resting behaviors. Foraging activity peaked during 08:00–09:00 h and again between 18:00–19:00 h, indicating preferred feeding times during cooler periods of the day. Flying behavior also showed peaks at 08:00–09:00 h and 16:00–17:00 h, while resting behavior was most frequent during 08:00–09:00 h and 12:00–17:00 h, with a peak at 16:00–17:00 h. Blue Lake serves as an ecologically important site for breeding, nesting, foraging, roosting, and a stopover for migratory birds along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway. Future management should prioritize a balanced coexistence between humans and birds through participatory management, with expert input from ornithologists and ecologists. PSU blue lake, a precious nature for human and birds in search for life happiness.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Research Subsidy for Pattani Campus Development, Fiscal Year 2025 (Project Code: SAT6703028S), Prince of Songkla University, Pattani Campus, Thailand. The authors gratefully acknowledge this funding support.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Somsak Buatip: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Visualization Supervision Project, Administration Funding Acquisition. Sitthisak Jantarat: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing – Review and Editing. Areena Truenae: Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft Preparation. Nurasiyah Teemasa: Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft Preparation. Tanakorn Chantasuban: Validation. Supaporn Saengkaew: Validation, Formal Analysis, Resources, Data Curation, Writing – Review and Editing, Visualization, Supervision. Supakan Buatip: Investigation. All authors have read and approved of the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they hold no competing interests.

REFERENCES

Aissaoui, R., Tahar, A., Saheb, M., Guergueb, L., and Houhamdi, M. 2011. Diurnal behaviour of Ferruginous Duck (Aythya nyroca) wintering at the El-Kala wetlands (northeast Algeria). Bulletin de l’Institut Scientifique, Section Sciences de la Vie. 33: 67-75.

Asokan, S., Ali, A.M.S., Manikannan, R., and Nithiyanandam, G.T. 2010. Population densities and diurnal activity pattern of the Indian Roller Coracias benghalensis (Aves: Coraciiformes) in Nagapattinam District, Tamil Nadu, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa. 2: 1185–1191. https://doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o2308.1185-91

Bird Conservation Society of Thailand. 2022. Revised Checklist of Thai birds July 2022. https://www.bcst.or.th/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Checklist_ThaiBirds_2022.xlsx

Bonter, D.N., Zuckerberg, B., Sedgwick, C.W., and Hochachka, W.M. 2013. Daily foraging patterns in free-living birds: Exploring the predation –starvation trade-off. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 280(1760): 20123087. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.3087

Brazil, M. 2009. Birds of East Asia. Princeton University Press, America.

Brennan, E.K., Smith, L.M., Haukos, D.A., and LaGrange, T.G. 2005. Short term response of wetland birds to prescribed burning in Rainwater Basin wetlands. Wetlands. 25(3): 667–674. https://doi.org/10.1672/0277-5212(2005)025[0667:SROWBT]2.0.CO;2

Buatip, S. and Chantasuban, T. 2021. Species and distribution of shorebirds in Pattani Bay. Burapha Science Journal. 26(1): 117-135.

Buatip, S., Chantasuban, T., Thongroy P., and Chavavongsa, C. 2022. Bird diversity in Prince of Songkla University area, Pattani Province. Burapha Science Journal. 27(3): 1889-1910.

Buatip, S., Karntanut, W., and Swennen, C. 2013. Nesting period and breeding success of the little egret Egretta garzetta in Pattani province, Thailand. Forktail. 29: 120-123.

Buatip, S., Karntanut, W., and Swennen, C. 2014. Food habit of little egrets (Egretta garzetta) at a colony in Pattani, Southern Thailand. Natural History Bulletin of the Siam Society. 60(1): 53-59.

Chantasuban, T., Buatip S., and Buatip, S. 2024. Bird diversity in paddy-field area, Nam Dam Sub-district, Thung Yang Daeng District, Pattani Province. Burapha Science Journal. 29(2): 463-480.

Chanthorn, W., Hartig, F., Brockelman, W.Y., Srisang. W., Nathalang, A., and Santon, J. 2019. Defaunation of large-bodied frugivores reduces carbon storage in a tropical forest of Southeast Asia. Scientific Reports. 9: 10015. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46399-y

Chowdhury, R., Sarkar, S., Nandy, A., and Talapatra, S.N. 2014. Assessment of bird diversity as bioindicators in two parks, Kolkata, India. International Letters of Natural Sciences. 16: 131-139. https://doi.org/10.56431/p-043hvp

Clements, J.F., Rasmussen, P.C., Schulenberg, T.S., Iliff, M.J., Fredericks, T.A., Gerbracht, J.A., Lepage, D., Spencer, A., Billerman, S.M. Sullivan, B.L., et al. 2024. The eBird/Clements checklist of Birds of the World: v2024. Downloaded from https://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2025. eBird [internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 March 2]. Available from: https://ebird.org/explore.

Deppe, F. 1999. Intertidal mudflats worldwide. Practical course at the Common Wadden Sea Secretariat (CWSS), Germany.

Díaz, L. 2006. Influences of forest type and forest structure on bird communities in oak and pine woodlands in Spain. Forest Ecology and Management. 223(1-3): 54-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2005.10.061

Fauzi, N.A., Munian, K., Mahyudin, N.A.A., and Norazlimi, N.A. 2025. Ecological insights on the feeding behaviour of waterbirds in an important bird and biodiversity area of South West Johor Coast, Malaysia. Biodiversity Data Journal. 13: e141250. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.13.e141250

Fayt, P. 2003. Insect prey population changes in habitats with declining vs. stable three-toed woodpecker Picoides tridactylus populations. Ornis Fennica. 80(4): 182–192.

Fernández, J.M., Selma, M.A.E., Aymerich, F.R., Sáez, M.T.P., and Fructuoso, M.F.C. 2005. Aquatic birds as bioindicators of trophic changes and ecosystem deterioration in the Mar Menor lagoon (SE Spain). Hydrobiologia. 550: 221-235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-005-4382-0

Graham, N.A.J., Wilson, S.K., Carr, P., Hoey, A.S., Jennings, S., and MacNeil, M.A. 2018. Seabirds enhance coral reef productivity and functioning in the absence of invasive rats. Nature. 559: 250-253. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0202-3

Grilli, M.G., Bildstein, K.L., and Lambertucci, S.A. 2019. Nature’s clean-up crew: Quantifying ecosystem services offered by a migratory avian scavenger on a continental scale. Ecosystem Services. 39: 100990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2019.100990

IUCN. 2025. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2025-1. [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2024 February 20]. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org.

Johnson, M., Kellermann, J., and Stercho A. 2010. Pest reduction services by birds in shade and sun coffee in Jamaica. Animal Conservation. 13(2): 140-147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2009.00310.x

Kasambe, R. 2005. Breeding behaviour of Blue-tailed Bee-eaters (Merops philippinus) in Central India. Newsletter for Birdwatchers. 45(1): 10-13.

Kassa, M., Balakrishnan, M., and Afework, B. 2021. Diurnal activity patterns, habitat use and foraging habits of Egyptian goose (Alopochena egyptiacus Linnaeus, 1766) in the Boyo wetland, southern Ethiopia. SINET: Ethiopian Journal of Science. 44(2): 182-192. https://doi.org/10.4314/sinet.v44i2.5

Lillywhite, H.B. and Brischoux, F. 2012. Is it better in the moonlight? Nocturnal activity of insular cotton mouth snakes increases with lunar light levels. Journal of Zoology. 286: 194–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.2011.00866.x

Lueangthuwapranit, C. 2019. Construction of low-cost Edible-Nest Swiftlet Houses (1st ed). Pattani info Co., Ltd., Pattani.

Maisey, A.C., Haslem, A., Leonard, S.W., and Bennett, A.F. 2021. Foraging by an avian ecosystem engineer extensively modifies the litter and soil layer in forest ecosystems. Ecological Applications. 31(1): e02219. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2219

Nabhitabhata, J., Lekagul, K., and Sanguansombat, W. 2007. Dr. Boonsong's bird guide of Thailand. Darnsutha Press, Bangkok.

Naniwadekar, R., Mishra, C., Isvaran, K., and Datta, A. 2021. Gardeners of the forest: Hornbills govern the spatial distribution of large seeds. Journal of Avian Biology. 52(11): e02748. https://doi.org/10.1111/jav.02748

Okore, O. and Amadi, C. 2016. Bird species of Mouau with special emphasis on foraging behavior of the northern grey-headed sparrow (Passer griseus). Animal Research International. 13(1): 2338-2344.

Patra, A. and Chowdhury, G. 2017. Behavioral ecology of blue tailed bee eaters (Merops philippinus) in Hooghly and Burdwan District of West Bengal, India. International Research Journal of Biological Sciences. 6(11): 31-35.

Piratelli, A., Sousa, S.D., Corrêa, J.S., Andrade, V.A., Ribeiro, R.Y., Avelar, L.H., and Oliveira, E.F. 2008. Searching for bioindicators of forest fragmentation: Passerine birds in the Atlantic forest of southeastern Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Biology. 68(2): 259-268. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842008000200006

Razaq, A., Forcina, G., Olsson, U., Tang, Q., Tizard, R., Lin, N., Pwint, N., and Khan, A.A. 2023. Phylogeography and diversification of Oriental weaverbirds (Ploceus spp.): A gradual increase of eurytopy. Avian Research. 14: 100-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avrs.2023.100120

Reinecke, K.J. 1981. Winter waterfowl research needs and efforts in the Mississippi Delta. International Waterfowl Symposium Transactions. 4: 231-236.

Ruttanadakul, N. and Ardsungnoen, S. 1985. Wader population’s around the Prince of Songkla University, Pattani campus, Southern Thailand. Proceedings of 6th Thailand Wildlife Seminar (pp. 224-251). Kasetsart University, Bangkok.

Ruttanadakul, N. and Chaipakdee, W. 1987. The studies of the status and some characteristics of the migratory Waterbird population in Pattani province. Faculty of Science and Technology, Pattani.

Sa-Ar, I., Limparungpatthanakij, W., Tonsakulrungruang, K., Nualsri, C., and Round, P.D. 2018. New bird records from the southern provinces of Thailand on the Thai-Malay Peninsula, 2005-2017. Birding ASIA. 29: 59-67.

Shannon, C.E. 1949. Mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal. 27: 379-423. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x

Sripanomyom, S., Round, P.D., Savini, T., Trisurat, Y., and Gale, G.A. 2011. Traditional salt-pans hold major concentrations of overwintering shorebirds in Southeast Asia. Biological Conservation. 144(1): 526-537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2010.10.008

Strong, A.M. and Sherry, T.W. 2000. Habitat-specific effects of food abundance on the condition of ovenbirds wintering in Jamaica. Journal of Animal Ecology. 69(5): 883-895. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2656.2000.00447.x

Swennen, C. and Marteijn, E.C.L. 1985. Feeding ecology studies in the Malay Peninsula. ln D. Parish, D.R. Wells (eds.) Interwader Annual Report 1984 (pp.13-26). Interwader, Kuala Lumpur.

Swennen, C. and Marteijn, E.C.L. 1988. Foraging behaviour of Spoon-billed Sandpipers Eurynorhynchus pygmeus on a mudflat in Peninsular Thailand. Natural History Bulletin of the Siam Society. 36: 85-88.

Tasirin, S.J. and Fitzsimons, J.A. 2014. Javan (White-vented) Myna Acridotheres javanicus and Pale-bellied Myna A. cinereus in North Sulawesi. Kukila. 18(1): 27-31.

The Chaipattana Foundation. 2008. Birds of Laem Phak Bia. Amarin Book Center Co., Ltd., Nonthaburi.

Tobgay, T. 2017. First record of Oriental Pratincole Glareola maldivarum for Bhutan. Birding ASIA. 27: 120-121.

Watson, D.M. and Herring, M. 2012. Mistletoe as a keystone resource: An experimental test. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279(1743): 3853-3860. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.0856

Whelan, C.J., Wenny, D.G., and Marquis, R.J. 2008. Ecosystem services provided by birds. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1134(1): 25-60. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1439.003

Woodall, P.F. and Kirwan, G.M. 2013. Black-capped Kingfsher (Halcyon pileata). In J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D.A. Christie, E. de Juana (eds.) Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Yuan, H.W., Burt, D.B., Wang, L.P., Chang, W.L., Wang, M.K., Chiou, C.R., and Ding, T.S. 2006. Colony site choice of blue-tailed bee-eaters: Influences of soil, vegetation, and water quality. Journal of Natural History. 40(7-8): 485-493. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222930600681043

OPEN access freely available online

Natural and Life Sciences Communications

Chiang Mai University, Thailand. https://cmuj.cmu.ac.th

Somsak Buatip1, 2, Sitthisak Jantarat1, 2, Areena Truenae3, Nurasiyah Teemasa3, Tanakorn Chantasuban1, 2, Supaporn Saengkaew1, 2, *, and Supakan Buatip3

1 Natural History Museum and Local Learning Network, Faculty of Science and Technology, Prince of Songkla University, Pattani campus, Pattani 94000, Thailand.

2 Department of Science, Faculty of Science and Technology, Prince of Songkla University, Pattani campus, Pattani 94000, Thailand.

3 Faculty of Education, Prince of Songkla University, Pattani campus, Pattani 94000, Thailand.

Corresponding author: Supaporn Saengkaew, E-mail: supaporn.sae@psu.ac.th

ORCID iD: Supaporn Saengkaew: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0301-0779

Sitthisak Jantarat: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-0376-0808

Somsak Buatip: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4933-0484

Supakan Buatip: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-7623-581X

Total Article Views

Editor: Wasu Pathom-a ree,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: May 25, 2025;

Revised: August 27, 2025;

Accepted: September 15, 2025;

Online First: September 23, 2025