Factors Associated With Loss to Follow-Up of Dental Implant Patients: A Retrospective and Questionnaire-Based Study

Sirimanas Jiaranuchart, Sappasith Panya, Chanyanuch Sahawutiwongsa, Natcha Pakasiriwattanakun, Rujravee Wongpaiboonwattana, and Keskanya Subbalekha*Published Date : June 20, 2025

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2025.052

Journal Issues : Number 3, July-September 2025

Abstract The long-term success of dental implants requires consistent follow-up, however, many patients do not attend these appointments. The factors associated with loss to follow-up (LTFU) remain unknown. This study consisted of two components: a retrospective analysis of dental records and a questionnaire survey of LTFU patients. Treatment records of dental implant patients treated at the Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University, were obtained from the faculty’s hospital database, with LTFU defined as no dental implant check-up record for over one year. A questionnaire was used to determine the reasons for LTFU. Of 698 patient records, 64.04% were LTFU. The 41-60 and 61-70 age groups had lower LTFU risk than those under 40 (OR = 0.6; 95% CI: 0.38 - 0.93; P = 0.02 and OR = 0.49, 95% CI: 0.30 - 0.80; P = 0.004). Half of patients became LTFU at 28 months, with the highest incidence in the first year. Among 208 survey respondents, 66.34% were unaware of the need for check-ups, and those unaware were more likely to schedule a visit (OR = 2.73; 95% CI: 1.48-5.57; P = 0.001). The main reason for LTFU was the lack of scheduled appointments by the dentists (22.6%). In conclusion, this study highlighted the critical importance of early patient education and improved communication strategies to reduce LTFU.

Keywords: Dental implant, Loss to follow-up, Maintenance, Recheck, Long-term success

Funding: This study was supported by the Dental Research Fund (Dental Research Project 3200502#17/2021), Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University.

Citation: Jiaranuchart, S., Panya, S., Sahawutiwongsa, C., Pakasiriwattanakun, N., Wongpaiboonwattana, R., and Subbalekha, K. 2025. Factors associated with loss to follow-up of dental implant patients: A retrospective and questionnaire-based study. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 24(3): e2025052.

INTRODUCTION

Dental implants are a prevalent and effective treatment for replacing missing teeth, demonstrating high success rates and patient satisfaction. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported dental implant survival rates exceeding 95% at the 10-year post-treatment follow-up (Howe et al., 2019). Moreover, more than 73% of the patients undergoing dental implant procedures expressed a high level of satisfaction across various aspects, e.g., esthetics, chewing ability, cleanliness, and phonetics (Wang et al., 2021; Pradyachaipimol et al., 2023).

To maintain the health and functionality of dental implants, self-care by patients and routine professional maintenance are required. Research indicates that a lack of regular implant maintenance correlates with peri-implant tissue inflammation (Monje et al., 2016; Monje et al., 2017; Atieh et al., 2022). Correct and regular implant maintenance has been shown to reduce the failure rate by 90% compared with no maintenance (Bidra et al., 2016; Gay et al., 2016), with at least one annual maintenance visit decreasing the failure rate by 60% (Gay et al., 2016).

Similar to natural teeth, the accumulation of bacterial plaque around dental implants can lead to peri-implant inflammation, resulting in biological complications termed peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis. Unlike natural teeth, the absence of a periodontium makes dental implants more susceptible to biomechanical pathology (Kim et al., 2005). Studies have indicated that a significant proportion of patients with dental implants exhibit signs of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis (Lee et al., 2017; Onclin et al., 2022). Additionally, mechanical complications, such as screw or implant body fractures, occur in 16.3-53.4% of cases within five years after treatment (Pjetursson et al., 2014), significantly impacting patient satisfaction (Wang et al., 2021; Pradyachaipimol et al., 2023).

Regular maintenance visits play a crucial role in reducing dental implant failures (Gay et al., 2016). Early detection and proper treatment of peri-implant mucositis can prevent its progression to peri-implantitis, an irreversible condition leading to implant loss. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated a decrease in peri-implantitis rates from 36.5% to 12.5% in patients who received at least two dental implant maintenance recalls per year (Monje et al., 2016).

Boonyatikarn et al. revealed that 37% of the dental implant patients at the FDCU were lost to follow-up (LTFU) immediately after the final restoration (Boonyatikarn et al., 2021). This discovery prompted a research question: "Why did a considerable number of implant patients fail to follow up?" Limited evidence on LTFU in dental implant patients requires a proactive approach to encourage patient participation in recall and maintenance visits. Understanding the reasons behind patients not having their dental implants rechecked is crucial for minimizing late complications and achieving long-term success. However, there is no report on the reasons why implant patients became LFTU.

The aim of this study was to identify the associated factors and investigate the reasons why dental implant patients at the FDCU did not undergo regular implant check-ups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The study consisted of a retrospective cohort analysis and a questionnaire-based survey, conducted in adherence to the STROBE guidelines (von Elm et al., 2014). The study protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand (HREC-DCU 2021-053).

Samples

To eliminate the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on dental visit lockdown, this study included patients who completed dental implant restoration at FDCU between 2014 and 2015. Individuals with no treatment record related dental implants for over one year were classified as LTFU.

Among them, those who had a follow-up period of less than 1 month or had never attended any visit after complete treatment were identified as a never-followed-up subgroup, while those who attended at least once were classified as ever-followed-up subgroup.

All LTFU patients were subsequently included in a questionnaire-based study and contacted by telephone. Those who could be reached were invited to participate by answering a structured questionnaire. Exclusion criteria included incomplete or unclear treatment records; documented referral to an external dental clinic for implant follow-up; inability to establish contact with the patient; insufficient proficiency in the Thai language; refusal to participate in the study; or a recorded history of implant failure.

The sample size was calculated using G*Power (version 3.1.9.2; Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Germany), employing a logistic regression model with sex as the predictor variable using data from Costa et al. (2023). The analysis was conducted with a significance level (α) of 0.05 and a statistical power (1−β) of 0.60, resulting in an estimated required sample size of 606 patients.

Data collection

Treatment records of patients who underwent dental implant placement and restoration at FDCU between January 2014 and December 2015 were retrieved using treatment fee codes from the hospital’s electronic database during October and December 2021. Each patient’s chart was retrospectively reviewed for a six-year period following the date of implant treatment completion.

Collected data included patient age at the time of implant treatment completion classified as ≤40, 41-60, 61-70, and ≥ 71 years old, sex, number of implants confirmed by treatment records and radiographs, implant locations classified as anterior, posterior, or both, type of prosthesis supported by the implant as either fixed or removable, and the departments responsible for surgical and prosthetic procedures, categorized as Educational Clinic (treatment provided by postgraduate students), Specialist Department (treatment by experienced specialist dentists), or Special Dental Clinic (treatment by experienced specialist dentists). The date of the last dental visit that included any documentation related to the implant was also recorded. The duration of dental implant follow-up was calculated from the date of implant treatment completion to the date of the last recorded visit with implant-related documentation.

According to previous study, patients with dental implants should be recalled for check-up visits every six months or yearly (Bidra et al., 2016; Gay et al., 2016). Similarly, the general follow-up protocol for dental implants at FDCU recommends check-ups every six months during the first year, and annually thereafter. Patients without an implant-related treatment record for over one year were classified as LTFU. LTFU patients who agreed to participate completed a phone questionnaire to explore reasons for LTFU.

Questionnaire development and administration

A structured questionnaire was developed to investigate the reasons for LTFU among dental implant patients. The questionnaire consisted of five items: (1) “Are you aware that your dental implant should be periodically rechecked?”; (2) “What is the major reason for not coming to follow-up?, choose only 1 best answer from the following 14 choices”; (3) “What are the minor reasons for not coming to follow-up?, choose any of the following 14 choices except the major reason chosen for your major reason”; (4) “Has the COVID-19 pandemic affected your ability to attend follow-up visits?”; and (5) “Would you like to schedule an implant check-up appointment at FDCU?”

All five questions were initially included in a pilot study involving 30 LTFU patients. Open-ended responses were collected for questions 2 and 3 to explore the reasons for non-attendance. These responses were thematically analyzed and categorized into 14 distinct reasons (Table 1), and appropriate changes were made to clarify specific questions that could generate ambiguity. The final structured questionnaire included three dichotomous questions (Items 1, 4, and 5) and two multiple-choice questions (Items 2 and 3). For question 2, participants selected one major reason, while question 3 allowed for multiple secondary reasons. The finalized questionnaire was administered to the target LTFU population via telephone interviews in Thai language. Responses were recorded as frequencies and percentages.

Table 1. Major and minor reasons leading LTFU.

|

Reasons |

Major reasons* |

Minor reasons** |

||

|

Ranking |

Number (n (%)) |

Ranking |

Number (n (%)) |

|

|

Their dentists did not schedule any appointments since the latest visit. |

1 |

47 (22.6) |

2 |

53 (19.6) |

|

Having regular dental health checked up by other clinics. |

2 |

33 (15.9) |

4 |

29 (10.7) |

|

Do not realize that dental implants require a routine checkup. |

3 |

22 (10.6) |

3 |

40 (14.8) |

|

No symptoms at the implant site. |

4 |

18 (8.7) |

1 |

72 (26.7) |

|

Waiting for a recall from the clinic but have never gotten any calls or contacts. |

5 |

16 (7.7) |

7 |

10 (3.7) |

|

Do not have time to have the implant rechecked. |

6 |

12 (5.8) |

10 |

5 (1.9) |

|

Concerned about COVID-19 pandemic. |

7 |

11 (5.3) |

6 |

14 (5.2) |

|

Moving to another city. |

8 |

10 (4.8) |

8 |

7 (2.6) |

|

Inconvenient to come for implant check-up at the FDCU. |

9 |

10 (4.8) |

5 |

17 (6.3) |

|

The recall appointment was postponed due to COVID-19 and have never gotten a new one yet. |

10 |

8 (3.9) |

14 |

3 (1.1) |

|

Their dentists informed them that they should return to the clinic only if they have symptoms at the implant site. |

11 |

7 (3.4) |

11 |

5 (1.9) |

|

The dental student who placed or restored the implant graduated and they did not know whom to contact. |

11 |

7 (3.4) |

12 |

4 (1.5) |

|

The visit had been canceled, and they did not know how to make another appointment. |

11 |

7 (3.4) |

8 |

7 (2.6) |

|

Do not know how to contact to make an appointment. |

14 |

0 |

12 |

4 (1.5) |

|

Total responses |

208 (100) |

270 (100) |

||

Note: * LTFU patients selected one major reason.

* LTFU patients were allowed for selecting multiple secondary reasons.

LTFU: Loss to follow-up, FDCU: Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University

Statistical analyses

The data were entered and analyzed using the SPSS statistical program version 22 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the demographic characteristics of the study population. Continuous variables, such as age, number of implants and follow-up duration, are presented as means with standard deviations. Differences in continuous variables between groups were assessed using t-tests. Categorical variables, including follow-up status, gender, age group, number of implants, implant location, clinic providing surgery, clinic providing restoration type of restoration, major and minor reasons of LTFU, awareness, dental implant follow-up participation, need to schedule new follow-up visit, and impact of COVID on dental visit were presented as frequencies and percentages.

The association between demographic factors and LTFU, demographic factors and awareness, awareness and dental implant follow-up participation, and awareness and need to schedule new appointment were assessed using simple binary logistic regression analysis. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to quantify the strength of these associations. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Additionally, to assess patient retention in follow-up care after implant treatment, a Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed. The event was defined as LTFU following the patient's latest follow-up visit. The survival time was calculated from the date of implant treatment completion to the date of the last recorded follow-up. Patients who continued to attend follow-up visits until the end of the observation period were censored. The incidence density of LTFU was calculated as the number of LTFU events per 100 person-years, using total person-time from implant treatment completion to LTFU or censoring.

RESULTS

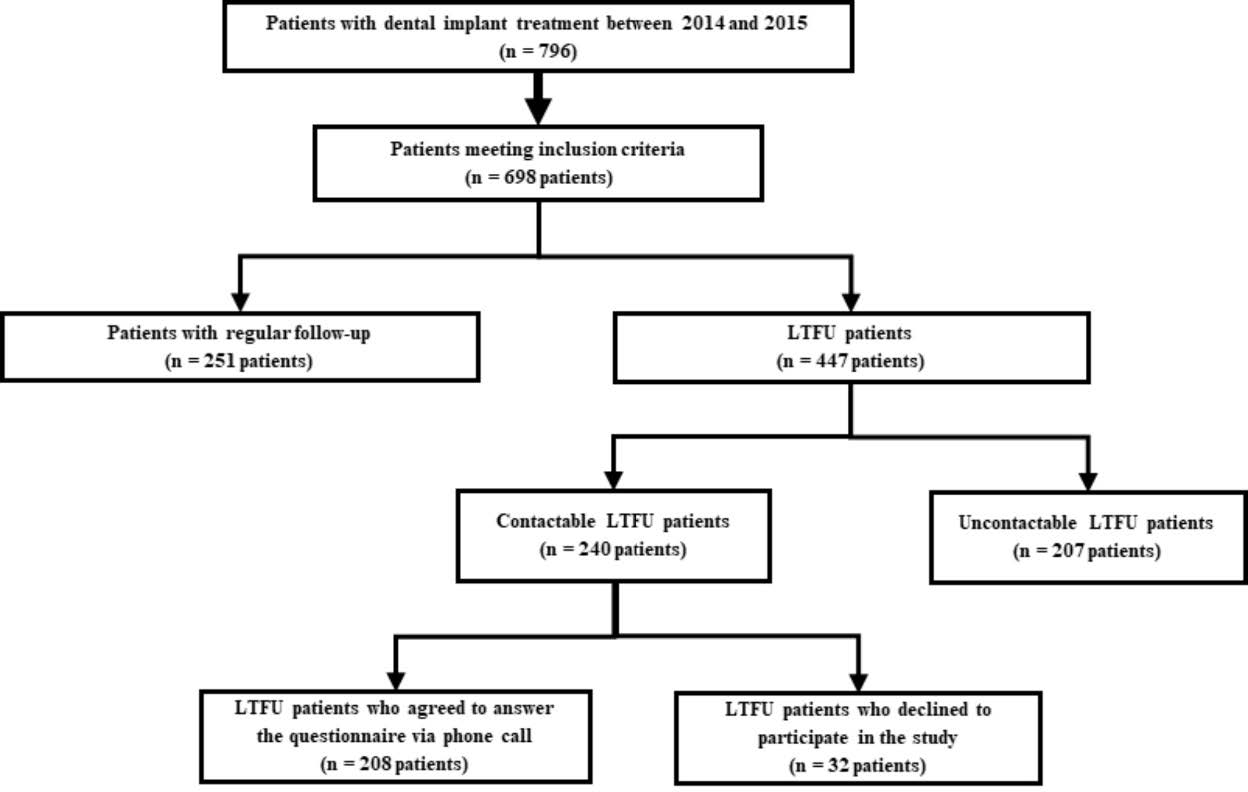

A total of 796 treatment records of dental implant patients who underwent dental implant placement and restoration at FDCU from January 2014 to December 2015 were collected during October and December 2021. In the retrospective analysis, 698 patients with 1,241 dental implants were included, while others were excluded due to unclear treatment records. Among these, 447 records were categorized in the LTFU group. Out of the 447 records, 240 could be contacted via phone call, and 208 agreed to answer the questionnaire, resulting in a high response rate of 86.67%.

Patient demographics

As shown in Table 2, among the 698 patients, 62.78% were female. The mean age of the patients was 52.86 ± 13.23 years, and the largest age group was 41-60 years old (49%). The distribution comprised 25.9%, 18.6%, and 5.6% of the patients in the 61-70 years old, less than 40 years old, and more than 71 years old, respectively, age groups.

On average, each patient had 1.58 ± 0.97 dental implants, with 61.7% having a single implant. Most of the patients had posterior implants (75.4%), and 18.2% and 5.9% had anterior implants and both anterior and posterior implants, respectively. Regarding the restoration, approximately 96.8% of the patients had fix prosthesis on implants and 3.2% having a bridge, a removable prosthesis and mixed restoration types, respectively.

Most of the patients (59.2%) received surgical treatment in the educational clinics, and 40% were treated by specialists in the Special Dental Clinic. For the prosthetic procedures, 41.3% and 38.3% of all patients were treated by specialists in Special dental clinic and postgraduate students in educational clinic, respectively. Another 13.8% received treatment in the Special Dental Clinic.

Factors associated with LTFU

In this study, demographic and clinical factors were evaluated for their association with LTFU among dental implant patients. Gender was not significantly associated with LTFU, with female patients exhibiting a slightly higher, but non-significant, likelihood of being lost to follow-up compared to male patients (OR = 1.11; 95% CI: 0.81–1.52; P = 0.52). In contrast, age demonstrated a statistically significant association. Patients aged 41–60 years (OR = 0.60; 95% CI: 0.38–0.93; P = 0.02) and 61–70 years (OR = 0.49; 95% CI: 0.30–0.80; P = 0.004) had significantly lower odds of being lost to follow-up compared to those aged ≤40 years, indicating that middle-aged and older patients were more likely to adhere to follow-up schedules. (Table 2)

Other variables, including the number of implants per patient, implant location, and the type of clinic providing surgical or prosthetic treatment, did not exhibit statistically significant associations with LTFU (all P > 0.05). Although patients with removable prostheses showed a lower likelihood of LTFU compared to those with fixed restorations (OR = 0.46; 95% CI: 0.19–1.07), this trend did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.07). Lastly the duration of follow-up was strongly associated with LTFU status; patients who were LTFU had a significantly shorter mean follow-up duration (13.7 months) compared to those who remained in dental implant follow-up (64.6 months) (P < 0.0001). (Table 2)

Table 2. Prevalence of LTFU and odds ratio of factors associated with LTFU among dental implant patients.

|

Demographic data |

Number (n (%)) |

OR |

P-value |

95%CI |

||||

|

LTFU |

FU |

Total |

||||||

|

Gender |

||||||||

|

Male |

167 (37.2) |

100 (39.8) |

267 (38.3) |

1.00 |

|

|||

|

Female |

280 (62.8) |

151 (60.2) |

431 (61.7) |

1.11 |

0.52 |

0.81- .52 |

||

|

Age |

52.3 ± 13.4 |

53.9 ± 12.9 |

52.9 ± 13.2 |

0.13 |

-0.48-3.68 |

|||

|

≤40 years old |

96 (21.8) |

34 (13.5) |

130 (18.6) |

1.00 |

|

|||

|

41-60 |

218 (48.8) |

128 (51) |

346 (49.6) |

0.60 |

0.02* |

0.38-0.93* |

||

|

61-70 |

107 (23.9) |

76 (30.3) |

183 (26.2) |

0.49 |

0.004* |

0.30-0.80* |

||

|

≥ 71 years old |

26 (5.9) |

13 (5.2) |

39 (5.6) |

0.71 |

0.38 |

0.33-1.53 |

||

|

Number of implant(s)/ patient |

1.6 ± 1.1 |

1.6 ± 0.9 |

1.6 ± 1.0 |

|

0.203 |

-0.25-0.05 |

||

|

1 |

281 (62.9) |

150 (59.8) |

431 (61.7) |

1.00 |

|

|||

|

2-3 |

148 (33.1) |

89 (35.5) |

237 (34.0) |

0.89 |

0.48 |

0.64-1.23 |

||

|

≥ 4 |

18 (4) |

12 (4.8) |

30 (4.3) |

0.80 |

0.56 |

0.38-1.71 |

||

|

Location of implants |

||||||||

|

Anterior region |

86 (18.7) |

44 (17.7) |

130 (18.2) |

1.00 |

|

|||

|

Posterior region |

337 (75.5) |

190 (76.3) |

527 (75.4) |

0.94 |

0.76 |

0.62-1.41 |

||

|

Both |

26 (5.8) |

15 (6) |

41 (5.9) |

0.92 |

0.82 |

0.44-1.91 |

||

|

Clinic providing surgery |

||||||||

|

Educational clinic |

258 (57.7) |

155 (61.8) |

413 (59.2) |

1.00 |

|

|||

|

Specialist department |

6 (1.3) |

0 (0) |

6 (0.9) |

|

||||

|

Special dental clinic |

183 (40.9) |

96 (38.2) |

279 (40.0) |

1.15 |

0.40 |

0.83-1.57 |

||

|

Clinic providing restoration |

||||||||

|

Educational clinic |

170 (38) |

97 (38.6) |

267 (41.0) |

1.00 |

|

|||

|

Specialist department |

52 (11.6) |

44 (17.5) |

96 (14.7) |

0.67 |

0.10 |

0.42-1.08 |

||

|

Special dental clinic |

189 (42.3) |

99 (39.4) |

288 (44.2) |

1.09 |

0.63 |

0.77-1.54 |

||

|

Types of restoration on implant |

||||||||

|

Fix prosthesis |

435 (97.8) |

238 (95.2) |

673 (96.8) |

1.00 |

|

|||

|

Removable prosthesis |

10 (2.2) |

12 (4.8) |

22 (3.2) |

0.46 |

0.07 |

0.19-1.07 |

||

|

Follow-up duration |

13.70 ± 19.60 |

64.60 ± 14.00 |

32.00 ± 30.22 |

< 0.0001* |

48.10-53.70* |

|||

Note: * Statistically significant at P ≤ 0.05 and 95%CI; LTFU, Loss to follow-up; FU, Follow-up; FDCU, Faculty of Dentistry Chulalongkorn University; OR, Odd ratio; 95%CI, 95% confident interval

LTFU status among dental implant patients

In this retrospective data collected in 2021, among the patients who received dental implant placement during 2014 and 2015, 447 (64%) were LTFU, and 251 (36%) were still adhering to the follow-up program. These patients were followed for a minimum of less than 1 month and a maximum of 72 months. Half of the patients were LTFU at 28 months after implant placement (95% CI: 19.5-36.5) (Figure 1).

The incidence density of LTFU was 10.67 per 100 person-years. The first year after implant placement revealed the highest incidence rate of LTFU at 48/100 person-years. Subsequently, the incidence rate of LTFU varied at different post-treatment durations: 9/100 person-years, 11/100 person-years, 13/100 person-years, and 6/100 person-years at the second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth years, respectively.

Figure 1. Flow diagram illustrating the study protocol and the number of participants in each stage of the study.

Awareness of patients on dental implants follow-up

To understand the reasons causing patients with dental implant rehabilitation to miss their follow-up visits, a survey was conducted with LTFU patients. 447 LTFU patients were contacted by phone call. Among them 240 were reachable, and 208 patients agreed to answer the questionnaire, resulting in an 86.67% response rate (Figure 2). The patients were predominantly women (62.0%), with a mean age of 51.46 ± 13.23 years. Nearly half of the patients (48.3%) were in the 40–60-year-old age group, and 24.6%, 22.7%, and 4.3% were in the ≤40, 61-70, and ≥71-year-old age groups, respectively. (Table 3)

The responses to "Do you know that your dental implant should have been rechecked?" revealed that 66.34% (138 patients) were unaware that they should have their implants checked every 6-12 months. All demographic and clinical factors were not significantly associated with awareness of the need for dental implant follow-up. Gender, age, implant location, type of surgical or restorative clinic, and type of prosthesis showed no statistically significant associations (P > 0.05). Interestingly, among the unaware patients, 51.4% had a follow-up period of less than 1 month (frequently associated with routine post-operative assessments following initial dental implant use) or never returned for implant check-ups after the prosthetic restoration was inserted. Only 39.1% of the aware patients (69 patients) had ever come for dental implant follow-up. Although patients in the ever-follow-up group demonstrated higher odds of awareness (OR = 0.543; 95% CI: 0.26 - 1.12; P = 0.09), this association did not reach statistical significance. The mean follow-up period of the unaware group was 3.67 months shorter than that of the aware group; however, the difference was not significant (P = 0.239; 95% CI: -9.82 - 2.47) (Table 3).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Mayer curve of six years cumulative LTFU rate among patients with dental implant.

Reasons for LTFU of dental implant-treated patients

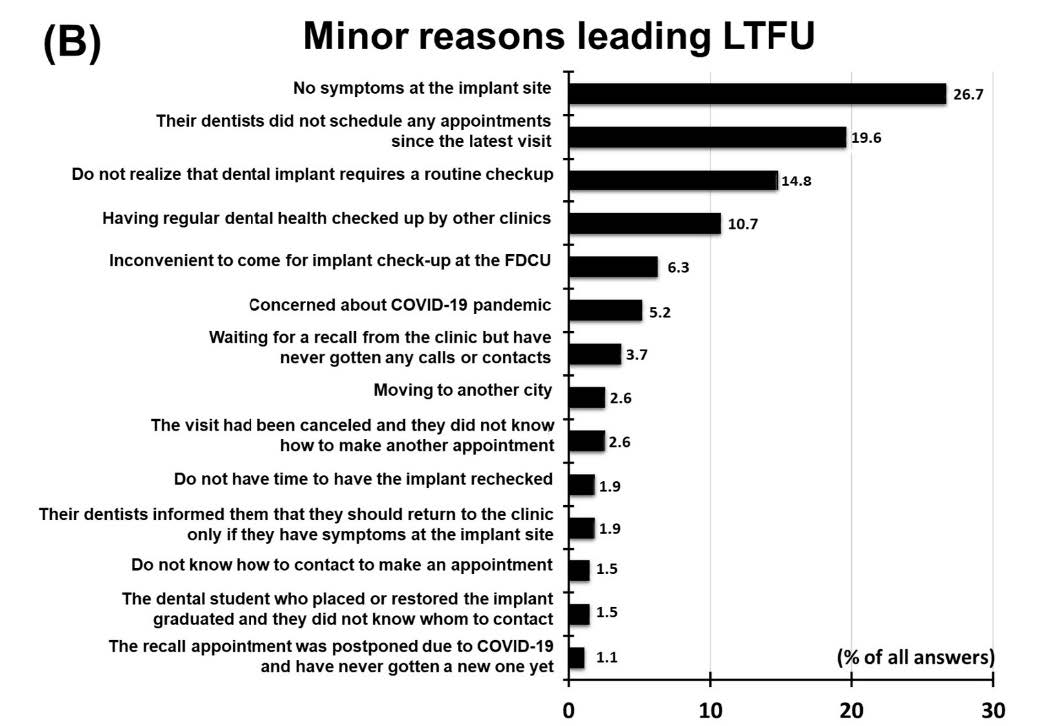

To identify the main reasons why the patients who received dental implants at FDCU were LFTU, the patients were asked to select one of 14 reasons prepared from the pilot study in response to the question, "What is the major reason for not coming to follow-up?" Among the 208 replies for the major reason for LTFU, the most frequently chosen major factor was their dentists' failure to schedule any appointments since the latest visit (22.6%), followed by having their dental health regularly checked at other clinics (15.9%), failing to realize the need for routine checkups for dental implants (10.6%), and the absence of any symptoms at the implant site (8.7%) (Table 1, Figure 3A).

Figure 3. The frequency of reasons for LTFU. major reasons (A) (Participants could choose only one best answer), minor reasons (B) (Participants were allowed to choose multiple contributing reasons).

To identify other associated reasons for LTFU, patients were asked to choose the minor reasons for LTFU. The patients provided 270 selections. No symptoms at the implant site were the most frequently cited minor reason (26.7%), followed by their dentists not scheduling any appointments since the latest visit (19.6%), failing to realize that dental implants require routine checkups (14.8%), and having their dental health regularly checked at other clinics (10.7%) (Table 1, Figure 3B).

Additionally, LTFU patients were asked for their attitudes on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the decision to attend or not to attend dental implant check-ups by using the question, “Has the COVID-19 pandemic affected your ability to attend follow-up visits?” One hundred and eight patients (51.92%) reported that the COVID-19 pandemic affected their dental follow-up visits.

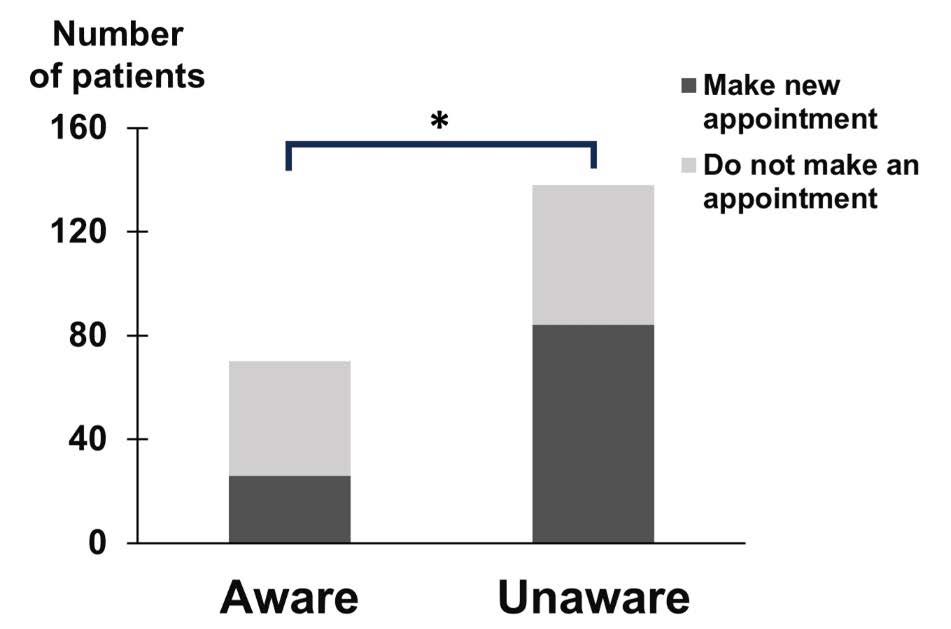

Lastly, the patients were asked, “Would you like to schedule an implant check-up appointment at FDCU?” One hundred and ten patients (52.88%) were willing to make an appointment for follow-up. Combining this information with the first question, 84 of 138 patients (60.78%) who were not aware of implant check-ups wanted to make an appointment for implant check-up, however, only 26 of 70 patients (37.14%) who were aware of implant check-ups wanted to make an appointment. The intention to make a new dental implant checkup visit was 2.73-fold significantly higher in the unaware patients compared with the other group (OR = 2.73; 95% CI: 1.48-5.57; P = 0.001) (Table 3, Figure 4).

Table 3. Prevalence of unawareness regarding dental implant follow-up and odds ratios for factors associated with awareness among lost to LTFU patients.

|

Factors |

Number (n (%)) |

OR |

P-value |

95%CI |

||||||

|

Unawareness |

Awareness |

Total |

||||||||

|

Gender |

|

|

||||||||

|

Male |

52 (37.7) |

27 (38.6) |

79 (38.0) |

1.000 |

|

|||||

|

Female |

86 (62.3) |

43 (61.4) |

129 (62.0) |

1.070 |

0.830 |

0.56-2.07 |

||||

|

Age |

51.28 ± 13.22 |

51.83 ± 13.35 |

51.46 ± 13.23 |

0.670 |

-3.27-4.41 |

|||||

|

≤40 years old |

32 (23.2) |

19 (27.5) |

19 (27.5) |

1.000 |

|

|||||

|

41-60 |

66 (47.8) |

34 (49.3) |

100 (48.3) |

0.429 |

0.331 |

0.08-2.36 |

||||

|

61-70 |

36 (26.1) |

11 (15.9) |

47 (22.7) |

0.356 |

0.212 |

0.07-1.80 |

||||

|

≥71 years old |

4 (2.9) |

5 (7.2) |

9 (4.3) |

0.213 |

0.078 |

0.04-1.19 |

||||

|

Location of implants |

|

|

||||||||

|

Anterior region |

27 (19.6) |

13 (18.6) |

40 (19.2) |

1.000 |

|

|||||

|

Posterior region |

105 (76.1) |

50 (71.4) |

115 (74.5) |

1.162 |

0.864 |

0.21-6.48 |

||||

|

Both |

6 (4.3) |

7 (10.0) |

13 (6.3) |

1.195 |

0.827 |

0.24-5.90 |

||||

|

Clinic providing surgery |

|

|||||||||

|

Educational clinic |

80 (58.0) |

35 (50.0) |

115 (55.3) |

1.000 |

|

|||||

|

Specialist department |

3 (2.2) |

3 (4.3) |

6 (2.9) |

1.275 |

0.698 |

0.3 -4.34 |

||||

|

Special dental clinic |

55 (39.9) |

32 (45.7) |

87 (41.8) |

1.239 |

0.856 |

0.12-12.47 |

||||

|

Clinic providing restoration |

|

|

||||||||

|

Educational clinic |

55 (39.9) |

18 (25.7) |

73 (35.1) |

1.000 |

|

|||||

|

Specialist department |

17 (12.3) |

12 (17.1) |

29 (13.9) |

0.986 |

0.985 |

0.23-4.30 |

||||

|

Special dental clinic |

58 (42.0) |

35 (50.0) |

93 (44.7) |

0.405 |

0.174 |

0.77-1.54 |

||||

|

Type of restoration on implant |

|

|

||||||||

|

Fix prosthesis |

137 (99.3) |

66 (94.3) |

203 (97.6) |

1.000 |

|

|||||

|

Removable prosthesis |

1 (0.7) |

4 (5.8) |

5 (2.4) |

0.365 |

0.456 |

0.03-5.17 |

||||

|

Dental implant follow-up participation |

|

|||||||||

|

Never |

71 (51.4) |

27 (38.6) |

98 (47.1) |

1.000 |

|

|

||||

|

Ever |

67 (48.6) |

43 (61.4) |

110 (52.9) |

0.543 |

0.090 |

0.26-1.12 |

||||

|

Need to schedule new follow-up visit |

|

|

||||||||

|

No |

54 (39.2) |

44 (62.9) |

98 (47.1) |

1.000 |

|

|

||||

|

Yes |

84 (60.8) |

26 (37.1) |

110 (52.9) |

2.730 |

0.001* |

1.48-5.75* |

||||

|

Follow-up duration |

14.80 ± 21.86 |

18.48 ± 19.49 |

16.90 ± 20.47 |

0.239 |

-9.82-2.47 |

|||||

Figure 4. Frequency of patients with implants who were aware and unaware of the necessity of dental implant follow-up. The group of unaware patients consisted of 60.78% of all LTFU patients who participated in the interview. These patients showed significantly higher frequencies of their need to make new dental implant check-up appointments than the aware group. (OR = 2.73; 95%CI: 1.48-5.75; P-value = 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

This aim of this retrospective, questionnaire-based study was to comprehensively investigate the associated factors and reasons related to LTFU in dental implant patients. According to Boonyatikarn et al. (2021), there were 2,734 dental implant patients at the FDCU between January 2014 and December 2018. To streamline the study and eliminate the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on LTFU, we included 698 patients who underwent implant placement from 2014 to 2015.

Despite the well-established benefits of regular maintenance visits in reducing the complications and failures of dental implants, emphasizing the importance of early detection and prevention of peri-implant diseases for long-term implant survival (Gay et al., 2016; Monje et al., 2016; Goh and Lim, 2017), the LTFU rate among patients receiving dental implant treatment at FDCU was notably high. The standard follow-up protocol at FDCU stipulated follow-up appointments every six months during the first postoperative year, transitioning to annual recalls thereafter. Consequently, this study defined patients with no implant-related treatment record at FDCU for a period exceeding one year as LTFU. In this six-year retrospective study, 64.04% of included patients were LTFU. This finding aligns with Brunello et al., where 84% of dental implant patients reported in the questionnaire that they did not attend follow-up visits (Brunello et al., 2020). In contrast, Derk et al.'s questionnaire-based study reported a high rate (79.1%) of annual follow-up visits among patients with dental implants (Derks et al., 2015), and Rentsch-Kollar et al. (2021) reported a very high recall attendance in patients with mandibular implant-retained dentures, exceeding 90% at the 10-year follow-up period (Rentsch-Kollar et al., 2010). Discrepancies in the LTFU rates among these studies may stem from variations in study design; since our study provided the actual LTFU rate from treatment records only at FDCU, others relied on patient self-reported questionnaires. These discrepancies may be attributed to differences in study design, as the present study utilized objective clinical records from a single institution, whereas other studies relied on patient self-reported questionnaires. Additionally, prosthesis type may influence follow-up behavior; the implant-retained overdentures assessed by Rentsch-Kollar et al. (2010) inherently require regular maintenance (e.g., replacement of retentive components), in contrast to the predominantly fixed prostheses in the current study. In addition, although one of the most frequently cited reasons for LTFU involved patients receiving implant maintenance outside of FDCU or attending the institution for unrelated dental services, such instances were not captured in our data. This exclusion was considered based on previous findings indicating that nearly half of general dentists are hesitant to manage implant maintenance due to insufficient training and lack of appropriate equipment (Rudeejaraswan et al., 2021). However, further investigation is necessary to elucidate additional factors influencing different LTFU rates.

Significant differences in the risk of LTFU were observed between age groups, with the youngest group having the highest risk, significantly higher than the 40-60 and 61-70 years old age groups, and higher than those 71 years and older. This contrasts with studies by Derk et al. (2015) and Wu et al. (2018) that reported higher LTFU rates in the older age group receiving dental implant and periodontal treatment. A similar age associated LTFU pattern was reported by Davies et al. (2016), where the no-show rate in clinic operational research decreased with increasing patient age, but a slightly increasing no-show rate was observed in patients more than 75 years old (Davies et al., 2016). The risk of LTFU may be influenced by health conditions, health awareness, and working status, varying between age groups.

In Thailand, where 60 years old is a common retirement age, younger patients under 60 may experience fewer oral health problems and limited free time due to work, negatively influencing dental visit attendance. Conversely, patients 61-70 years old might have no time restrictions and be healthy enough to attend dental visits, resulting in the lowest risk of LTFU in this age group. The increasing risk of LTFU in patients aged 70 and older may be influenced by their health conditions, limiting their ability to attend follow-up dental visits.

Sex, the number of implants in each patient, implant location, type of implant restoration, and the type of clinic providing the surgery or restoration were not associated with the LTFU rate. This aligns with Sugihara et al. (2010), Tandon et al. (2016), and Wu et al. (2018), who found that sex did not play a significant role in patients missing dental appointments. However, systematic reviews by George et al. (2007), Oberoi et al. (2014), and Hajek et al. (2021) reported an association between sex and patient attendance in dental services. Additionally, no significant difference was observed in the LTFU rates between the educational clinics and special clinics providing either the surgical or restorative procedures. Educational clinics, where treatment is performed by dental students, offer direct patient contact, while special clinics may involve more complicated procedures, leading to difficulties in contacting the hospital after the students graduate.

To estimate the time to LTFU among patients who received dental implants, this study found that approximately half of the patients were LTFU at 28-weeks after implant placement. Among these patients, approximately half had a follow-up period of less than one month or never attended an implant check-up visit. Interestingly, the incidence rate of LTFU in the first year was ~5-fold higher than in the subsequent years, suggesting that patients who participated in the follow-up program for more than one year after implant placement were more likely to adhere to the dental implant check-up program in the following years. This emphasizes the importance of making appointments or providing encouragement to patients to participate in dental implant follow-up visits during the first year after implant placement. However, because this is the first report on the time to LTFU in dental implant patients, further studies in different environments or conditions are required.

To investigate the reasons behind LTFU, the questionnaire contained 14 reasons obtained from a pilot study. These reasons can be categorized into two groups: hospital-related and patient-related factors (eight reasons). Patients were asked to choose one of the 14 reasons as the major reason for LTFU and two or three as minor reasons. The three most common major reasons for LTFU were dentists not making appointments since the last visit, patients were receiving regular dental checks at other clinics, and patients not realizing that dental implants require routine

check-ups.

The most common minor reason for LTFU reported by dental implant patients was the absence of symptoms at the implant site. Similar reasons causing the missing of dental implant maintenance and regular dental recall visits were reported by other studies (Devaraj and Eswar, 2012; Brunello et al., 2020). Other studies have noted that the cost of dental treatment or patient income (Australian Research Centre for Population Oral Health, 2008; Oberoi et al., 2014; Tu et al., 2023) and forgetfulness (Shabbir et al., 2018) are common reasons for irregular dental attendance. However, dental implant patients did not specifically mention these factors. This discrepancy could be attributed to the distinctive characteristics of dental implant patients, who may have the financial means to afford high-cost treatments, such as dental implants. Nevertheless, it was undeniable that socioeconomic status (SES) and health literacy are factors known to influence dental service utilization (Australian Research Centre for Population Oral Health, 2008; Oberoi et al., 2014; Tu et al., 2023). Common misconceptions about implants among Thai patients with dental implant (e.g., Dental implants require less maintenance or carry no risk of treatment) may also contribute to LTFU (Vipattanaporn et al., 2019). In addition, many studies stated that patients often presented themselves for dental care at the later stages of dental disease when overt symptoms are present, and people do not believe in the value of regular dental visits (Sugihara et al., 2010; Currie et al., 2021). Therefore, these mentioned factors should be investigated for their association with LTFU. Also, they suggested that dental practitioners should educate patients about the importance of regular dental care.

Interestingly, 66.34% of all patients did not know that dental implants should be periodically checked. After being informed of the importance of regular dental implant check-ups, 60.9% of previously uninformed patients expressed an intent to make a new appointment, however, only 37% of patients who were already aware of the importance of dental implant check-ups wanted to make new appointments. Therefore, dentists and dental staff should inform and re-emphasize the need for maintenance, including when the patient does not exhibit symptoms, and provide clear information to decrease misunderstanding and misinterpretation, especially during the first year after treatment completion. Based on the study results, we recommend that dentists make recall appointments for their implant patients to retain them in the system (Brunello et al., 2020). Additionally, a missed dental appointment policy should be programmed and clearly explained to the patient, including messaging, calling, and reminders 2-3 days before the appointment (Parikh et al., 2010; Prasad and Anand, 2012). Difficulty in contacting the dental office and making an appointment has often been mentioned. Some patients complained that because the hospital did not provide a 1-year recall schedule and no reminder call, they had to record the date and make a booking in advance themselves. Moreover, they felt it was complicated to make an appointment.

In addition, given the significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the healthcare system (Prajapati et al., 2021), this study also reports the effect of the pandemic on the LTFU of dental implant patients. Half of the dental implant patients reported the influence of COVID-19 on their decision to attend dental visits, including dental implant check-ups. In González et al. (2022), patients more than 60 years old expressed reluctance to go to the dentist due to the fear of COVID-19 infection. However, dental implant follow-up is considered a low-risk procedure for disease transmission because no aerosol is generated during the treatment. Therefore, communication with patients about the precautions in dental clinics and the risk of infection plays a crucial role in reducing patients' anxiety and fear (Salgarello et al., 2022). It is assumed that without the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of LTFU patients would have been lower.

A key strength of this study is its comprehensive design, combining retrospective record analysis with a prospective questionnaire survey for both quantitative assessment of LTFU rates and qualitative exploration of patient attitudes and reasons for LTFU. The large sample size and high response rate strengthen the reliability of the findings, while the use of clinical records provides a more objective measure than self-reported adherence. Analysis of factors such as age, awareness, and intent to return yields actionable insights for improving follow-up care. Nevertheless, as it was conducted at a single academic institution, the generalizability of the findings to other settings, such as private clinics or rural populations, may be limited, though the inclusion of patients from both educational and special clinics, which differ in treatment costs and dentist experiences, introduced some diversity. The retrospective design may result in incomplete data, and treatment records lacked important variables such as dental anxiety, SES, and health literacy. Further study should employ these factors in the investigation.

While the questionnaire identified key reasons for LTFU, reliance on self-reported data introduces potential recall and social desirability biases, and fixed response options may not fully capture individual experiences. Additionally, institutional barriers such as insufficient staffs to manage missed appointments were not evaluated. Furthermore, this study employed only univariate logistic regression without adjusting for potential confounders. Future research should apply multivariate logistic regression to better identify independent predictors of LTFU and account for interrelated factors.

Despite these limitations, the study makes a strong contribution by highlighting the critical importance of early patient education and improved communication strategies to reduce LTFU and enhance the long-term success of dental implants.

CONCLUSION

This research sheds light on the high rate of LTFU among dental implant patients, emphasizing the need for proactive measures to educate and encourage patients, particularly during the critical first year post-treatment. Dentists should prioritize informing patients about the necessity of regular implant check-ups, dispelling misconceptions, and implementing effective appointment scheduling systems. The impact of external factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, should be considered in patient communication strategies. Overall, this study provides valuable insights to improve patient adherence to dental implant follow-up programs, contributing to the long-term success of dental implants.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University. The authors are grateful to OMFS Department residents for facilitating. We thank Dr. Kevin Tompkins for revising the language in this manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sirimanas Jiaranuchart: Designed the research method, collected the data, conducted the analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript.

Sappasith Panya: Analyzed and interpreted the data, and contributed to manuscript writing.

Chanyanuch Sahawutiwongsa, Natcha Pakasiriwattanakun Rujravee, Wongpaiboonwattana: Collected the data, conducted the analysis and contributed to manuscript writing.

Keskanya Subbalekha: Designed the research method, conducted the analysis and interpretation, and critically revised manuscript.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATION

This research was approved by the Human Research Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University (HREC-DCU 2021-053).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they hold no competing interests.

REFERENCES

Atieh, M.A., Almutairi, Z., Amir-Rad, F., Koleilat, M., Tawse-Smith, A., Ma, S., Lin, L., and Alsabeeha, N.H.M. 2022. A retrospective analysis of biological complications of dental implants. International Journal of Dentistry. 2022: 1545748.

Australian Research Centre for Population Oral Health. 2008. Factors associated with infrequent dental attendance in the Australian population. Australian Dental Journal. 53(4): 358-362.

Bidra, A.S., Daubert, D.M., Garcia, L.T., Gauthier, M.F., Kosinski, T.F., Nenn, C.A., Olsen, J.A., Platt, J.A., Wingrove, S.S., Chandler, N.D. et al. 2016. A systematic review of recall regimen and maintenance regimen of patients with dental restorations. Part 2: Implant-borne restorations. Journal of Prosthodontics. 25 Suppl 1: S16-S31.

Bidra, A.S., Daubert, D.M., Garcia, L.T., Kosinski, T.F., Nenn, C.A., Olsen, J.A., Platt, J.A., Wingrove, S.S., Chandler, N.D., and Curtis, D.A. 2016. Clinical practice guidelines for recall and maintenance of patients with tooth-borne and implant-borne dental restorations. Journal of the American Dental Association. 147(1): 67-74.

Boonyatikarn, C., Srisopon, P., Sookjadit, W., and Subbalekha, K. 2021. Dental implant treatment at the faculty of dentistry Chulalongkorn university: 5-year data analysis. The Journal of the Dental Association of Thailand. 71(1): 1-8.

Brunello, G., Gervasi, M., Ricci, S., Tomasi, C., and Bressan, E. 2020. Patients' perceptions of implant therapy and maintenance: A questionnaire-based survey. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 31(10): 917-927.

Costa, F.O., Costa, A.M., Ferreira, S.D., Lima, R.P.E., Pereira, G.H.M., Cyrino, R.M., Oliveira, A.M.S.D., Oliveira, P.A.D., and Cota, L.O.M. 2023. Long-term impact of patients' compliance to peri-implant maintenance therapy on the incidence of peri-implant diseases: An 11-year prospective follow-up clinical study. Clinical Implant Dentistry and Related Research. 25(2): 303-312.

Currie, C.C., Araujo-Soares, V., Stone, S.J., Beyer, F., and Durham, J. 2021. Promoting regular dental attendance in problem-orientated dental attenders: A systematic review of potential interventions. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 48(10): 1183-1191.

Davies, M.L., Goffman, R.M., May, J.H., Monte, R.J., Rodriguez, K.L., Tjader, Y.C., and Vargas, D.L. 2016. Large-scale no-show patterns and distributions for clinic operational research. Healthcare (Basel). 4(1): 15.

Derks, J., Hakansson, J., Wennstrom, J.L., Klinge, B., and Berglundh, T. 2015. Patient-reported outcomes of dental implant therapy in a large randomly selected sample. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 26(5): 586-591.

Devaraj, C. and Eswar, P. 2012. Reasons for use and non-use of dental services among people visiting a dental college hospital in india: A descriptive cross-sectional study. European Journal of Dentistry. 6(4): 422-427.

Gay, I.C., Tran, D.T., Weltman, R., Parthasarathy, K., Diaz-Rodriguez, J., Walji, M., Fu, Y., and Friedman, L. 2016. Role of supportive maintenance therapy on implant survival: A university-based 17 years retrospective analysis. International Journal of Dental Hygiene. 14(4): 267-271.

George, A.C., Hoshing, A., and Joshi, N.V. 2007. A study of the reasons for irregular dental attendance in a private dental college in a rural setup. Indian Journal of Dental Research. 18(2): 78-81.

Goh, E.X.J. and Lim, L.P. 2017. Implant maintenance for the prevention of biological complications: Are you ready for the next challenge? Journal of Investigative and Clinical Dentistry. 8(4).

González-Olmo, M.J., Delgado-Ramos, B., Ortega-Martínez, A.R., Romero-Maroto, M., and Carrillo-Díaz, M. 2022. Fear of covid-19 in madrid. Will patients avoid dental care? International Dental Journal. 72(1): 76-82.

Hajek, A., Kretzler, B., and Konig, H.H. 2021. Factors associated with dental service use based on the andersen model: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 18(5): 2491.

Howe, M.S., Keys, W., and Richards, D. 2019. Long-term (10-year) dental implant survival: A systematic review and sensitivity meta-analysis. Journal of Dentistry. 84: 9-21.

Kim, Y., Oh, T.J., Misch, C.E., and Wang, H.L. 2005. Occlusal considerations in implant therapy: Clinical guidelines with biomechanical rationale. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 16(1): 26-35.

Lee, C.T., Huang, Y.W., Zhu, L., and Weltman, R. 2017. Prevalences of peri-implantitis and peri-implant mucositis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Dentistry. 62: 1-12.

Monje, A., Aranda, L., Diaz, K.T., Alarcon, M.A., Bagramian, R.A., Wang, H.L., and Catena, A. 2016. Impact of maintenance therapy for the prevention of peri-implant diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Dental Research. 95(4): 372-379.

Monje, A., Wang, H.L., and Nart, J. 2017. Association of preventive maintenance therapy compliance and peri-implant diseases: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Periodontology. 88(10): 1030-1041.

Oberoi, S.S., Mohanty, V., Mahajan, A., and Oberoi, A. 2014. Evaluating awareness regarding oral hygiene practices and exploring gender differences among patients attending for oral prophylaxis. Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology. 18(3): 369-374.

Onclin, P., Slot, W., Vissink, A., Raghoebar, G.M., and Meijer, H.J.A. 2022. Incidence of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis in patients with a maxillary overdenture: A sub-analysis of two prospective studies with a 10-year follow-up period. Clinical Implant Dentistry and Related Research. 24(2): 188-195.

Parikh, A., Gupta, K., Wilson, A.C., Fields, K., Cosgrove, N.M., and Kostis, J.B. 2010. The effectiveness of outpatient appointment reminder systems in reducing no-show rates. The American Journal of Medicine. 123(6): 542-548.

Pjetursson, B.E., Asgeirsson, A.G., Zwahlen, M., and Sailer, I. 2014. Improvements in implant dentistry over the last decade: Comparison of survival and complication rates in older and newer publications. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 29 Suppl: 308-324.

Pradyachaipimol, N., Tangsathian, T., Supanimitkul, K., Sophon, N., Suwanwichit, T., Manopattanasoontorn, S., Arunyanak, S.P., and Kungsadalpipob, K. 2023. Patient satisfaction following dental implant treatment: A survey. Clinical Implant Dentistry and Related Research. 25(3): 613-623.

Prajapati, A., Gupta, S., Nayak, P., Gulia, A., and Puri, A. 2021. The effect of covid-19: Adopted changes and their impact on management of musculoskeletal oncology care at a tertiary referral centre. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 23: 101651.

Prasad, S. and Anand, R. 2012. Use of mobile telephone short message service as a reminder: The effect on patient attendance. International Dental Journal. 62(1): 21-26.

Rentsch-Kollar, A., Huber, S., and Mericske-Stern, R. 2010. Mandibular implant overdentures followed for over 10 years: Patient compliance and prosthetic maintenance. The International Journal of Prosthodontics. 23(2): 91-98.

Rudeejaraswan, A., Pisarnturakit, P.P., Mattheos, N., Pimkhaokham, A., and Subbalekha, K. 2021. Dentists’ attitudes toward dental implant maintenance in Thailand. JDR Clinical & Translational Research. 8(1): 76-84.

Salgarello, S., Audino, E., Bertoletti, P., Salvadori, M., Garo, M.L. 2022. Dental patients’ perspective on COVID-19: A systematic review. Encyclopedia. 2(1): 365-382.

Shabbir, A., Alzahrani, M., and Abu Khalid, A. 2018. Why do patients miss dental appointments in eastern province military hospitals, kingdom of Saudi Arabia? Cureus. 10(3): e2355.

Sugihara, N., Tsuchiya, K., Hosaka, M., Osawa, H., Yamane, G.Y., and Matsukubo, T. 2010. Dental-care utilization patterns and factors associated with regular dental check-ups in elderly. The Bulletin of Tokyo Dental College. 51(1): 15-21.

Tandon, S., Duhan, R., Sharma, M., and Vasudeva, S. 2016. Between the cup and the lip: Missed dental appointments. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 10(5): ZC122-ZC124.

Tu, R.Y., Liang, P., Tan, A.J., Tran, D.H.G., He, A.M., Je, H., and Kroon, J. 2023. Factors associated with regular dental attendance by aged adults: A systematic review. Gerodontology. 40(3):277-287.

Vipattanaporn, P., Mattheos, N., Pisarnturakit, P., Pimkhaokham, A., and Subbalekha, K. 2019. Post-treatment patient-reported outcome measures in a group of Thai dental implant patients. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 30: 928–939.

von Elm, E., Altman, D.G., Egger, M., Pocock, S.J., Gotzsche, P.C., Vandenbroucke, J.P., and Initiative, S. 2014. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (strobe) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. International Journal of Surgery. 12(12): 1495-1499.

Wang, Y., Baumer, D., Ozga, A.K., Korner, G., and Baumer, A. 2021. Patient satisfaction and oral health-related quality of life 10 years after implant placement. BMC Oral Health. 21(1): 30.

Wu, D., Yang, H.J., Zhang, Y., Li, X.E., Jia, Y.R., and Wang, C.M. 2018. Prediction of loss to follow-up in long-term supportive periodontal therapy in patients with chronic periodontitis. PLoS One. 13(2): e0192221.

OPEN access freely available online

Natural and Life Sciences Communications

Chiang Mai University, Thailand. https://cmuj.cmu.ac.th

Sirimanas Jiaranuchart1, 2, Sappasith Panya1, 2, Chanyanuch Sahawutiwongsa3, Natcha Pakasiriwattanakun3, Rujravee Wongpaiboonwattana3, and Keskanya Subbalekha1, 2,*

1 Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Digital Implant Surgery Research Unit, Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand.

2 Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand.

3 Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand.

Corresponding author: Keskanya Subbalekha, E-mail: skeskanya@gmail.com

ORCID:

Sirimanas Jiaranuchart: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8403-275X

Keskanya Subbalekha: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1570-2289

Total Article Views

Editor: Anak Iamaroon,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: September 17, 2024;

Revised: May 20, 2025;

Accepted: May 30, 2025;

Online First: June 20, 2025