Digital Media Consumption Patterns and Development of Preschool Children: Developing a Manual to Enhance Media Literacy in Parents of Children Facing Developmental Challenges

Kannika Permpoonputtana, Jongkon Doungsri, Sarun Kunwittaya, Thirata Khamnong, and Nonthasruang Kleebpung*Published Date : June 17, 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2024.043

Journal Issues : Number 3, July-September 2024

Abstract This study examined parents' and preschool digital media consumption, formulating a manual to enhance media literacy in parents of preschool children with developmental challenges. In the first phase, the research explored digital media patterns among Thai parents and preschoolers, investigating their association with developmental outcomes. Questionnaires and the Denver II test assessed digital media usage and child development. Following phase 1, the media literacy manual was developed and validated using item-objective congruence. The second phase evaluated the manual's effectiveness using a media literacy questionnaire with six elements. In the first phase, 97 parent-child pairs participated, with 48 (49.48%) children experiencing developmental delays. The results offer insights into digital media usage patterns, revealing that the majority of parents use digital media daily for 1-3 hours, with no significant difference between normal and delayed development groups. Regarding children's habits, a significant majority engage daily, with most spending less than 30 minutes. Children with normal development use digital media more frequently but for shorter durations compared to those with delayed development. The media literacy manual for parents of children facing developmental challenges underwent evaluation using an IOC, ensuring its reliability validity with values ranging from 0.66 to 1.00. Phase 2, the participants included 41 parents from Phase 1. In Phase 2, 41 parents of children with developmental delays who participated in Phase 1 were included. Initially, the sample group scored 15.89 on overall media literacy knowledge. After studying the media literacy manual, their score increased to 19.02, indicating a statistically significant improvement at the 0.001 level, as determined by paired t-test statistics. Initially, the sample group scored 15.89 on overall media literacy knowledge, and after the training program, the media literacy score increased to 19.02, signifying a statistically significant improvement at the 0.001 level according to paired t-test statistics.

Keywords: Media literacy, Digital media, Developmental challenges, Preschool children

Funding: This project is supported by the Health Systems Research Institute (HSR).

Citation: Permpoonputtana, K., Doungsri, J., Kunwittaya, S., Khamnong, T., and Kleebpung, N. 2024. Digital media consumption patterns and development of preschool children: Developing a manual to enhance media literacy in parents of children facing developmental challenges. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 23(3): e2024043.

INTRODUCTION

Early childhood is a period in which children reach crucial developmental milestones (Scharf et al., 2016). Environmental factors may promote or hinder this sensitive process. Among these influencing factors, media exposure has been discussed concerning its effect on early childhood development (Barr and Linebarger, 2016; Linebarger and Vaala, 2010). Preschoolers are now growing up in environments saturated with a variety of media environments. Digital media devices like television, computers, mobile phones, and recently touchscreen gadgets, have become inseparable parts of the daily life of every person including children (Neumann, 2015). World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines suggest limiting young children’s screen time to a maximum of 1 h per day (Organization, 2019). More children are using interactive and mobile media, daily (Chen and Adler, 2019; Kabali et al., 2015). Likewise, >90% of Thai infants have been exposed to at least one form of electronic screen media at the age of <12 months (Chonchaiya et al., 2015). Unsurprisingly, these children have begun to be exposed to any screen media since birth, particularly background television where programs on the television are intended for adults and always on. As a result, young individuals are unattended by their caregivers (Chonchaiya et al., 2015). Moreover, the duration of all electronic screen media the Thai infants aged 6–12 months have been exposed to, is >4 h per day (Vijakkhana et al., 2015). This earlier and heavy media exposure has been documented to be associated with violence (Strasburger et al., 2012), obesity (Strasburger et al., 2012), sleep problems (Brown and Media, 2011; Jolin and Weller, 2011), decreased parent-child interactions (Mendelsohn et al., 2008; Kirkorian et al., 2009), delayed language development (Chonchaiya and Pruksananonda, 2008; Christakis et al., 2009; Tomopoulos et al., 2010), impairments in cognitive function (Tomopoulos et al., 2010; Lillard and Peterson, 2011), and behavioral problems (Zimmerman and Christakis, 2007; Cheng et al., 2010; Jolin and Weller, 2011; Chonchaiya et al., 2015).

In the early years of childhood, family is the most important factor in children’s development. Children are initially educated in the family environment and their parents are accepted as their first educators. Children learn many things around by observing their surroundings in their preschool period and during this period, parents are deterministic models for them (Ceka and Murati, 2016). In the realm of parenting and childhood development, the significance of parental media literacy in the context of children facing developmental challenges cannot be overstated. As technology continues to play a pervasive role in our daily lives, understanding and navigating media landscapes become crucial skills for caregivers. This necessitates a focused exploration into the parents and preschool digital media consumption, aiming not only to comprehend existing knowledge but also to formulate comprehensive manual. This introduction delves into the imperative task of enhancing media literacy in parents, recognizing its pivotal role in fostering a supportive environment for the holistic development of children facing developmental challenges.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study comprised two distinct phases: 1) Investigating digital media consumption patterns among parents and preschool children, and exploring the association between digital media consumption and the developmental outcomes of preschool children. 2) Developing and assessing the effectiveness of a parental media literacy manual targeted at parents with children encountering developmental challenges. The research adhered to ethical principles and received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Mahidol University (MUSSIRB COA No. 2021/030.11030 and IPSR-IRB COA No. 2019/02-057).

Participants and Procedures

Phrase 1: Investigating digital media consumption among parents and preschool children, and exploring the correlation between digital media consumption and the developmental outcomes of preschool children.

In the first phase, the investigation focused on discerning patterns of digital media consumption among Thai parents and preschool children, along with an exploration of the association between such consumption and the developmental outcomes of preschool children. This involved the utilization of questionnaires in a cross-sectional study to assess the digital media usage patterns of parents and preschool children. Additionally, developmental assessments were conducted using the Denver II developmental screening test to examine the correlation between digital media consumption and the developmental outcomes of preschool children.

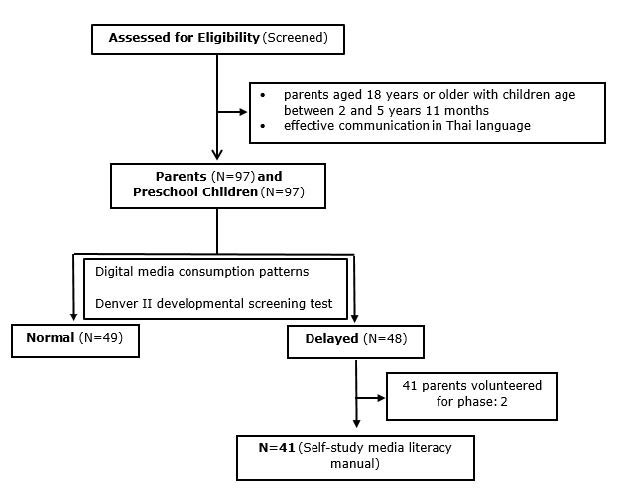

The participant selection process employed a purposive sampling method, with eligibility criteria stipulating those participants needed to be parents aged 18 years or older with children age between 2 and 5 years 11 months. Proficiency in the Thai language was a prerequisite for effective communication, and participants were required to provide informed consent and willingly complete the questionnaire. Before initiating the testing phase, written consent was obtained from all parents for their child's participation. The sample size was determined a priori using G*Power, with 80% power and alpha = 0.05, assuming a medium effect size informed by meta-analytic research synthesizing studies on media use in young children's (0–6 years) vocabulary learning and development, which reported medium effect sizes (Jing et al., 2023). A total of 97 parent-child pairs were recruited from Nakhon Pathom and Chonburi provinces, as depicted in Figure 1. Detailed demographic characteristics of parents and children are presented in Table 1, indicating an average child age of 4.12 ± 1.11 years, with 56 boys and 41 girls. Of the participants, 48 children (49.48%) experienced developmental delays. Parents, averaging 35.36 ± 7.00 years in age, included 23 males and 74 females, with the majority having completed a bachelor's degree and reporting a monthly income exceeding 50,000 bath/month.

Phrase 2: Developing and assessing the effectiveness of a parental media literacy manual targeted at parents with children encountering developmental challenges.

Following the completion of phase 1, the research team developed a media literacy manual based on existing literature to enhance the media literacy of parents dealing with children confronting developmental challenges. Content validity was assessed by calculating the item-objective congruence (IOC) value for each item. The clarity ratings from three experts in media literacy and child development were aggregated, and the IOC was determined by dividing the summed score by the number of experts. An IOC value of 0.5 or higher was considered satisfactory, following the criteria established by Rovinelli and Hambleton (1977) (Rovinelli and Hambleton, 1977). Subsequently, the second phase aimed to assess the effectiveness of the parental media literacy manual designed for parents with children facing developmental challenges. The media literacy levels before and after the self-study of the manual were measured using a media literacy questionnaire developed by the researchers. Both the media literacy manual and questionnaire comprised six elements: the impact of media on development, appropriate media for early childhood, knowledge support about media, media analysis, assessment of media values, and media creativity.

In this stage, participant selection employed a purposive sampling method, drawing from volunteers from Phase 1. Eligibility criteria dictated that participants needed to be parents aged 18 years or older, having children age between 2 and 5 years 11 months who were identified as facing developmental challenges according to previous survey results. Proficiency in the Thai language was essential for effective communication, and participants were obligated to give consent willingly and complete the questionnaire. Before initiating the testing phase, written consent was obtained from all parents for their child's participation. A total of 41 parents of children facing developmental challenges were recruited, as depicted in Figure 1. Detailed demographic characteristics of parents and children are presented in Table 2, indicating an average child age of 4.22±1.26 years, with 26 boys and 15 girls. Parents, averaging 33.66±5.11 years in age, included 9 males and 32 females, with the majority having completed a bachelor's degree and reporting a monthly income 45,001-50,000 bath/month.

Figure 1. Study flowchart.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of children (N=97) and parents (N=97) in phrase 1.

|

Demographic Variable |

Normal (N=49) |

Delayed (N=48) |

Total |

|||||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|||

|

Children |

Age, Mean ± SD |

4.13 ± 1.05 |

4.17 ± 1.21 |

4.12 ± 1.11 |

||||

|

Sex |

Male |

25 |

51.00 |

31 |

64.60 |

56 |

57.70 |

|

|

|

Female |

24 |

49.00 |

17 |

35.40 |

41 |

42.30 |

|

|

Parents |

Age, Mean ± SD |

37.80 ± 7.18 |

33.17 ± 5.9 |

35.36 ± 7.00 |

||||

|

Sex |

Male |

12 |

24.49 |

11 |

22.92 |

23 |

23.71 |

|

|

|

Female |

36 |

75.51 |

38 |

77.08 |

74 |

76.29 |

|

|

Educational Level |

Less than bachelor |

12 |

24.50 |

21 |

43.80 |

33 |

34.00 |

|

|

Bachelor |

19 |

38.80 |

23 |

47.90 |

42 |

43.30 |

||

|

Higher than bachelor |

17 |

34.70 |

3 |

6.30 |

20 |

20.60 |

||

|

Others |

1 |

2.00 |

1 |

2.10 |

2 |

2.10 |

||

|

Monthly Income (Baht) |

< 15,000 |

8 |

16.30 |

4 |

8.30 |

12 |

12.40 |

|

|

15,000-30,000 |

5 |

10.20 |

7 |

14.60 |

12 |

12.40 |

||

|

30,001-45,000 |

5 |

10.20 |

10 |

20.80 |

15 |

15.50 |

||

|

45,001-50,000 |

10 |

20.40 |

8 |

16.70 |

18 |

18.60 |

||

|

> 50,000 |

21 |

42.90 |

19 |

39.60 |

40 |

41.20 |

||

Table 2 Demographic characteristics of parents (N=41) in phrase 2.

|

Demographic Variable |

Total |

|||

|

N |

% |

|||

|

Children |

Age, Mean ± SD |

4.22 ± 1.26 |

||

|

Sex |

Male |

26 |

63.40 |

|

|

|

Female |

15 |

36.60 |

|

|

Parents |

Age, Mean ± SD |

33.66 ± 5.11 |

||

|

Sex |

Male |

9 |

21.95 |

|

|

|

Female |

32 |

78.05 |

|

|

Educational Level |

Less than bachelor |

16 |

39.00 |

|

|

Bachelor |

22 |

53.70 |

||

|

Higher than bachelor |

3 |

7.30 |

||

|

Others |

0 |

0 |

||

|

Monthly Income (Baht) |

< 15,000 |

4 |

9.80 |

|

|

15,000-30,000 |

10 |

24.40 |

||

|

30,001-45,000 |

8 |

19.50 |

||

|

45,001-50,000 |

19 |

46.30 |

||

|

> 50,000 |

4 |

9.80 |

||

Measures

The research tools for the first cross-sectional phase consisted of 3 parts for collecting data. The demographic questionnaire was used for collecting demographic information of the children and parents. To assess the digital media usage of parents and children, the questionnaires about the frequency and duration of digital media use (Appendix A) were administered by caregivers. The clarity of the questionnaires was evaluated by three experts in media literacy and child development, resulting in an IOC value for each item ranging from 0.5 to 1, indicating validity.

Additionally, all children underwent developmental assessments using the Denver II developmental screening test. This test used to evaluate the global development of children ages 0 to 6 years old, is composed of 125 items divided into four domains: personal-social, fine motor-adaptive, language, and gross motor. The corrected age was used at the ages of 1 and 2 years. Each item was scored according to cutoff points previously defined as “delay” when a child cannot perform an item that 90 % of children of the same age can perform successfully, and “caution” occurs when a child fails to complete an item that 75 %–90 % of children of the same age can perform. Based on the number of delays and cautions, the child's development was classified as: “suspect”, when the child had one or more delays and/or two or more cautions; and “normal” when the child had a caution and no delay (Frankenburg et al., 1992).

In the second phase, the researcher developed a tool to assess parents' media literacy (Appendix B), consisting of 30 questions with four answer choices each, as well as a media literacy manual (Appendix C) aimed at parents of children with developmental challenges. The content validity of the tool was evaluated using the IOC value for each question, with all questions demonstrating an IOC value exceeding 0.5, which is considered acceptable. Both the questionnaires and the parental media literacy manual encompass six fundamental aspects of media literacy: (1) the impact of media on development, (2) appropriate media for early childhood, (3) knowledge about media access, (4) knowledge of media analysis, (5) knowledge about media valuation, and (6) knowledge about creating media content.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out utilizing SPSS 23.0 software. Descriptive statistics, encompassing percentages, means, and standard deviations, were computed for demographic variables and participant characteristics. The normality of all data was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The association between various variables and child development was investigated through the chi-square test. To assess the disparity in parents' media literacy levels before and after learning from the media literacy manual, paired samples t-tests were conducted for normally distributed data, while the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was employed for non-normally distributed data. In this study, significance was considered at P < 0.05.

RESULT

Parents' and children's digital media usage

Table 3. presents data on the digital media usage patterns of parents and children, with a focus on the frequency, duration, and periods of digital media consumption. The table is divided into sections, each addressing specific aspects of digital media usage:

Parents' Frequency and Duration: The first part describes parents' frequency and duration of digital media use. It indicates that the majority of parents use media every day, with minimal variations between normal and delayed development groups. The chi-square test indicates no significant difference in this aspect. The duration of time parents spend on digital media. The majority of parents spend 1-3 hours, and the chi-square test suggests a marginal level of significance (P = 0.080).

Children's Frequency and Duration: The next section delves into children's digital media usage patterns in terms of frequency and duration. It highlights that every day, children in the normal development group use digital media more frequently than those in the delayed development group, and the chi-square test shows a significant difference (P = 0.000). Most children spend less than 30 minutes. Interestingly, children in the normal development group spend less time on digital media compared to their delayed development counterparts, and this difference is statistically significant (P= 0.000).

Children's Time Period: The final part examines the time periods during which children engage with digital media. The data indicate variations in media usage across different time periods, such as morning, late morning, afternoon, evening, and night. The chi-square test suggests a non-significant difference (P = 0.128).

Table 3. Parents and child digital media usage.

|

Patterns of digital media use |

Normal (N=49) |

Delayed (N=48) |

df |

c2 |

p-value |

|||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

|||||

|

Parents: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frequency, Mean±SD |

1.00 ± 0.00 |

Everyday |

1.04 ± 0.20 |

Everyday |

1 |

2.09 |

0.24 |

|

|

|

|

100.00 |

46 |

95.80 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.00 |

2 |

4.20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.00 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.00 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

Duration, Mean±SD |

2.41 ± 0.91 |

1-3 hrs. |

2.35 ± 1.15 |

1-3 hrs. |

3 |

6.76 |

0.08 |

|

|

|

|

14.3 |

14 |

29.20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

44.9 |

15 |

31.30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

26.5 |

7 |

14.60 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14.3 |

12 |

25.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

Children: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frequency, Mean±SD |

1.00 ± 0.00 |

Every day |

1.46 ± 0.71 |

Every day |

2 |

19.56 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

|

100.00 |

32 |

66.70 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.00 |

10 |

20.80 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.00 |

6 |

12.50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.00 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

Duration, Mean±SD |

1.59 ± 0.49 |

< 30 min. |

1.85 ± 1.01 |

< 30 min. |

3 |

21.46 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

|

40.80 |

24 |

50.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

59.20 |

11 |

22.90 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.00 |

9 |

18.80 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.00 |

4 |

8.30 |

|

|

|

|

|

Time period, Mean±SD |

4.06 ± 1.11 |

Evening |

3.54 ± 1.25 |

Afternoon |

4 |

7.16 |

0.12 |

|

|

|

|

6.10 |

4 |

8.30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.00 |

7 |

14.60 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14.30 |

8 |

16.70 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

34.70 |

17 |

35.40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

42.90 |

12 |

25.00 |

|

|

|

|

The media literacy level of parents

The findings from Table 4. illustrate the distribution of parental knowledge levels across various aspects of media literacy. When considering the impact of media on parental development, the majority of participants (43.9 percent) displayed a moderate level of understanding (3 points), with 34.1 percent at a low level (0-2 points) and 22.0 percent at a high level (4-5 points). Regarding comprehension of media suitable for early childhood, 41.5 percent scored at a low level, 36.6 percent at a moderate level, and 22.0 percent at a high level on the 5-point scale. In terms of proficiency in media access, 36.6 percent demonstrated high-level knowledge, 26.8 percent had a lower level of proficiency, and 68.3 percent displayed high-level understanding in media analysis. For evaluating the value of media, the majority (70.7 percent) had a low-level understanding, 26.8 percent displayed a moderate level, and 2.4 percent had a high level. In creating media content, 80.5 percent exhibited a high level, while a combined 9.8 percent displayed a lower or moderate level. Table 4. The media literacy level of parents

Table 4. The distribution of parental knowledge levels across various aspects of media literacy.

|

Media literacy |

Level, N (%) |

||

|

Low |

Moderate |

High |

|

|

14 (34.10) |

18 (43.90) |

9 (22.00) |

|

17 (41.50) |

15 (36.60) |

9 (22.00) |

|

11 (26.80) |

15 (36.60) |

15 (36.60) |

|

4 (9.80) |

9 (22.00) |

28 (68.30) |

|

29 (70.70) |

11 (26.80) |

1 (2.40) |

|

4 (9.80) |

4 (9.80) |

33 (80.50) |

Content validity of the media literacy manual

The content validity, assessed using an IOC index, covers six key areas crucial for promoting media literacy among parents, as detailed in Table 5. The IOC values range from 0.66 to 1.00, indicating good content validity.

Table 5. The outcomes of content validity are based on the IOC index for each Media literacy component.

|

Media literacy component |

Expert |

IOC |

Result |

||

|

# 1 |

# 2 |

# 3 |

|||

|

1 |

1 |

0 |

0.66 |

Accept |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1.00 |

Accept |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1.00 |

Accept |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1.00 |

Accept |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1.00 |

Accept |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1.00 |

Accept |

Media literacy knowledge among parents before and after training intervention

The parents in the sample group exhibited an average score of 15.89 for overall media literacy knowledge before participating in the training program aimed at enhancing their understanding. The standard deviation for this pre-training period was 2.66. Following the training program, designed to promote knowledge in media literacy, the sample group of parents showed an increased overall mean score of 19.02, with a standard deviation of 4.58. Before conducting statistical tests, the distribution of the data was examined. Homogeneity tests indicated that the data were homogeneous. Upon comparing the average scores of media literacy knowledge before and after utilizing the manual for promoting media literacy knowledge, as determined by paired t-test statistics, it was revealed that parents' media literacy knowledge increased after using the guide. This increase was statistically significant at the 0.001 level, as shown in Table 6.

The study assessed the impact of a media literacy training program on parents' knowledge in various aspects. The findings from Table 7, the analysis included the effects of media on development, appropriate use of media for early childhood, media access, media analysis, evaluating the value of media, and media content creation. The results, determined using the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test due to the non-normal distribution of the data, show no significant change in knowledge about the effects of media on parental development and the suitable use of media for early childhood. However, there was a notable increase in knowledge about media access, which was statistically significant. Additionally, the training significantly improved knowledge about media evaluation and media content creation among the participating parents

(P < 0.05).

Table 6. Comparative assessment of media literacy knowledge among parents (N=41) before and after training intervention.

|

Media literacy (Total Score) |

Mean ± SD |

t |

P-value (1-tailed) |

|

Before |

15.880 ± 2.660 |

-4.990*** |

<0.001 |

|

After |

19.020 ± 4.580 |

Table 7. Comparative examination of media literacy knowledge in each component before and after participating in the training manual to enhance media literacy understanding among parents.

|

Media literacy component |

Before Median (IQR) |

After Median (IQR) |

Z |

P-value (1-tailed) |

|

3.000 (1.000) |

3.000 (1.500) |

-1.660 |

0.097 |

|

3.000 (1.000) |

3.000 (1.000) |

-1.800 |

0.073 |

|

3.000 (2.000) |

4.000 (1.000) |

-3.020** |

0.003 |

|

4.000 (1.000) |

4.000 (2.000) |

-1.260 |

0.209 |

|

2.000 (2.000) |

3.000 (2.000) |

-3.240* |

0.01 |

|

1.000 (1.500) |

2.000 (1.000) |

-4.020*** |

<0.001 |

Note: IQR= Interquartile range, *P < 0.05

DISCUSSION

This study focused on the exploration of parents and preschool digital media consumption and formulated comprehensive manual for parental media literacy of children encountering developmental challenges. The results provide valuable insights into the nuanced patterns of digital media usage among both parents and children, shedding light on the frequency, duration, and time periods of engagement. The fact that the majority of parents, regardless of their child's developmental status, use digital media every day. Moreover, the absence of a significant difference between normal and delayed development groups in this regard suggests a shared media usage pattern among parents. When considering the duration of time parents spend on digital media, the finding that most allocate 1-3 hours is noteworthy. Although the chi-square test indicates a marginal level of significance, this may imply a general trend among parents in dedicating a moderate amount of time to digital media activities.

While this study found no significant differences in media use behavior between parents of children with typical development and those with developmental delays, a recent systematic review indicated that parental smartphone use negatively impacts parental responsiveness and attention toward children aged 3 years or younger (Knitter and Zemp, 2020). Another systematic review examining the use of mobile devices by parents and the social and emotional development of children aged 10 years or younger revealed that parents were less engaged, exhibited harsher responses, and had fewer verbal and nonverbal interactions with their children when using mobile devices (Beamish et al., 2019).

Turning to children's media habits, it is evident that a significant majority engage with digital media daily, with the majority allocating less than 30 minutes to this activity. This aligns with recommended guidelines advocating for the restriction of screen time for young children to a maximum of 1 hour per day (Organization, 2019). The observed results indicate a noteworthy difference in the digital media usage patterns between children with normal development and those with delayed development. Specifically, children with normal development demonstrated a higher frequency of digital media use compared to their counterparts with delayed development. This suggests that children in the normal development group engage with digital media more frequently within a given time frame. Interestingly, despite the higher frequency, children with normal development exhibited a shorter duration of engagement with digital media. These findings are supported by recent studies indicating that Children who had developmental delays spent more time watching television than normal children (Vandewater et al., 2005; Chonchaiya and Pruksananonda, 2008; Felix et al., 2020).

According to the literature, a clear and widely recognized definition of media literacy was established approximately twenty years ago. Media literacy includes four components-access, analysis, evaluation, and content creation-providing a comprehensive, skills-based framework for understanding media literacy (Patricia and Firestone Charles, 1993; Christ and Potter, 1998; Aufderheide, 2018). The media literacy manual in this study was specifically designed for parents of children with developmental challenges, with an added focus on the impact of media on child development and appropriate media for early childhood. The manual underwent a thorough examination by three experts to ensure its accuracy and effectiveness. The assessment addressed critical aspects of promoting media literacy among parents, covering six key areas: the impact of media on child development, appropriate media for early childhood, media access, media analysis, media evaluation, and creating media content. To gauge the reliability of the manual, the evaluation employed an IOC, a valuable metric that provides a comprehensive measure of the content's accuracy. The IOC values, ranging from 0.66 to 1.00, indicate a high level of consistency across the six areas under consideration. This suggests that the manual successfully maintains accuracy and coherence in addressing essential elements of media literacy. Subsequently, when parents utilized the media literacy manual, an examination of parents' media literacy level before studying the manual unveiled diverse levels of knowledge across distinct aspects of media literacy in parents of children facing developmental delays. This offered valuable insights into the intricate dynamics of how parents comprehend and interact with media. Firstly, in terms of the impact of media on child development, it is noteworthy that a substantial proportion of participants demonstrated a moderate level of understanding. Secondly, when considering comprehension of media suitable for early childhood, the distribution across low, moderate, and high levels highlights the diversity in parents' awareness of age-appropriate media content for young children. In terms of proficiency in media access, the substantial percentage of parents demonstrating high-level knowledge is encouraging. This suggests that a considerable portion of parents possess the skills to navigate and access media effectively. However, the presence of a lower proficiency group indicates a digital divide that needs attention. The high level of understanding in media analysis is a positive finding, indicating that a majority of parents possess the skills to critically analyze media content. This is crucial in the context of guiding children's media use, as parents who can analyze media content effectively are better equipped to make informed decisions regarding its appropriateness for their children. When evaluating the value of media, the prevalent low-level understanding among parents signals a potential area for improvement. Lastly, the high proficiency observed in creating media content suggests that a significant number of parents actively engage in producing or curating content for their children. This highlights an opportunity for initiatives that harness and support parents' creativity in creating positive and educational media experiences for their children.

Following the parents utilizing the media literacy promotion manual, designed to promote knowledge in media literacy, upon comparing the average scores of media literacy knowledge before and after utilizing the manual for promoting media literacy knowledge, it was revealed that parents' media literacy knowledge significantly increased after using the guide. The substantial increase in media literacy scores post-training signifies the positive impact of the designed manual in enhancing parents' understanding and proficiency in media literacy. The statistical significance further strengthens the credibility of these findings, highlighting the effectiveness of the training manual in positively influencing the media literacy knowledge of the participating parents. This outcome not only emphasizes the success of the training program but also underscores its potential as a valuable resource for improving media literacy among parents, thereby fostering more informed and responsible media-related practices within families.

Several limitations were identified in the current study. Despite offering valuable insights into the media literacy of parents with children facing developmental delays, it is crucial to recognize specific constraints. Firstly, the study's sample size may limit the applicability of the findings, given its focus on a particular demographic. Moreover, the reliance on self-reported data might introduce response bias. The predominant use of quantitative methods in the study leaves room for a more comprehensive investigation using qualitative approaches, which could have provided a deeper understanding of parents' experiences. Additionally, the assessment of the media literacy promotion manual's effectiveness immediately after use suggests a need for a longitudinal evaluation to capture its long-term impact. Lastly, the study did not assess the influence of parental media literacy on children's media use and development post-study, posing a potential gap in understanding the extended outcomes.

CONCLUSION

This study highlights the prevalent use of digital media among both parents and preschool children in Thailand and underscores the importance of media literacy, particularly for parents of children with developmental delays. The successful development and validation of a tailored media literacy manual mark a crucial step toward empowering these parents, ultimately contributing to more informed and beneficial media consumption practices.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research participants, and parents were gratefully acknowledged.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, Kannika Permpoonputtana, Jongkon Doungsri, and Nonthasruang Kleebpung, Data curation, Kannika Permpoonputtana, Jongkon Doungsri, Sarun Kunwittaya and Nonthasruang Kleebpung; Formal analysis, Kannika Permpoonputtana, and Jongkon Doungsri; Investigation, Kannika Permpoonputtana, and Jongkon Doungsri; Methodology, Kannika Permpoonputtana, Jongkon Doungsri, and Nonthasruang Kleebpung,; Project administration, Kannika Permpoonputtana, and Nonthasruang Kleebpung; Resources, Nonthasruang Kleebpung; Software, Kannika Permpoonputtana; Supervision, Nonthasruang Kleebpung; Validation, Nonthasruang Kleebpung; Visualization Kannika Permpoonputtana, Thirata Khamnong and Jongkon Doungsri; Writing – original draft, Kannika Permpoonputtana, and Jongkon Doungsri;; Writing – review & editing, Kannika Permpoonputtana, and Nonthasruang Kleebpung.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Aufderheide, P., ed. 1993 . Media literacy: A report of the national leadership conference on media literacy, Aspen, CO: Aspen Institute.

Aufderheide, P. 2018. Media literacy: From a report of the national leadership conference on media literacy. Media Literacy Around the World, Routledge: 79-86.

Barr, R., and Linebarger, D.N. 2016. Media exposure during infancy and early childhood (pp. 978-973). Springer International Publishing, Switzerland.

Beamish, N., Fisher, J., and Rowe, H. 2019. Parents’ use of mobile computing devices, caregiving and the social and emotional development of children: A systematic review of the evidence. Australasian Psychiatry. 27(2): 132-143.

Brown, A. and Council on Communications and Media. 2011. Media use by children younger than 2 years. Pediatrics. 128 (5): 1040–1045.

Ceka, A., and Murati, R. 2016. The role of parents in the education of children. Journal of Education and Practice. 7(5): 61-64.

Chen, W., and Adler, J.L. 2019. Assessment of screen exposure in young children, 1997 to 2014. JAMA Pediatrics. 173(4): 391-393.

Cheng, S., Maeda, T., Yoichi, S., Yamagata, Z., Tomiwa, K., and Japan Children’s Study Group. 2010. Early television exposure and children’s behavioral and social outcomes at age 30 months. Journal of Epidemiology. 20 (Supplement_II): S482-S489.

Chonchaiya, W., and Pruksananonda, C. 2008. Television viewing associates with delayed language development. Acta Paediatrica. 97(7): 977-982.

Chonchaiya, W., Sirachairat, C., Vijakkhana, N., Wilaisakditipakorn, T., and Pruksananonda, C. 2015. Elevated background TV exposure over time increases behavioural scores of 18‐month‐old toddlers. Acta Paediatrica. 104(10): 1039-1046.

Christ, W.G., and Potter, W. J. 1998. Media literacy, media education, and the academy. Journal of Communication. 48(1): 5-15.

Christakis, D.A., Gilkerson, J., Richards, J.A., Zimmerman, F.J., Garrison, M.M., Xu, D., Gray, S., and Yapanel, U. 2009. Audible television and decreased adult words, infant vocalizations, and conversational turns: a population-based study. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 163(6): 554-558.

Felix, E., Silva, V., Caetano, M., Ribeiro, M.V., Fidalgo, T.M., Rosa Neto, F., Sanchez Z.M., Surkan, P.J., Martins, S.S, and Caetano, S.C. 2020. Excessive screen media use in preschoolers is associated with poor motor skills. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 23(6): 418-425.

Frankenburg, W.K., Dodds, J., Archer, P., Shapiro, H., and Bresnick, B. 1992. The Denver II: A major revision and restandardization of the Denver Developmental Screening Test. Pediatrics. 89(1): 91-97.

Jing, M., Ye, T., Kirkorian, H. L., and Mares, M. L. 2023. Screen media exposure and young children's vocabulary learning and development: A meta‐analysis. Child Development. 94(5): 1398-1418.

Jolin, E.M., and Weller, R.A. 2011. Television viewing and its impact on childhood behaviors. Current Psychiatry Reports. 13: 122-128.

Kabali, H.K., Irigoyen, M.M., Nunez-Davis, R., Budacki, J.G., Mohanty, S.H., Leister, K.P., and Bonner Jr, R.L. 2015. Exposure and use of mobile media devices by young children. Pediatrics. 136(6): 1044-1050.

Kirkorian, H.L., Pempek, T.A., Murphy, L.A., Schmidt, M.E., and Anderson, D.R. 2009. The impact of background television on parent–child interaction. Child Development. 80(5): 1350-1359.

Knitter, B., and Zemp, M. 2020. Digital family life: A systematic review of the impact of parental smartphone use on parent-child interactions. Digital Psychology. 1(1): 29-43.

Lillard, A.S., and Peterson, J. 2011. The immediate impact of different types of television on young children's executive function. Pediatrics. 128(4): 644-649.

Linebarger, D.L., and Vaala, S.E. 2010. Screen media and language development in infants and toddlers: An ecological perspective. Developmental Review. 30(2): 176-202.

Mendelsohn, A.L., Berkule, S.B., Tomopoulos, S., Tamis-LeMonda, C.S., Huberman, H.S., Alvir, J., and Dreyer, B.P. 2008. Infant television and video exposure associated with limited parent-child verbal interactions in low socioeconomic status households. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 162(5): 411-417.

Neumann, M.M. 2015. Young children and screen time: Creating a mindful approach to digital technology. Australian Educational Computing. 30(2).

World Health Organization. 2019. Guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep for children under 5 years of age. World Health Organization.

Rovinelli, R.J. and Hambleton, R.K. 1977. On the use of content specialists in the assessment of criterion-referenced test item validity. Dutch Journal for Educational Research. 2: 49–60.

Scharf, R.J., Scharf, G.J., and Stroustrup, A. 2016. Developmental milestones. Pediatrics in review. 37(1): 25-38.

Strasburger, V.C., Jordan, A.B., and Donnerstein, E. 2012. Children, adolescents, and the media: Health effects. Pediatric Clinics. 59(3): 533-587.

Tomopoulos, S., Dreyer, B.P., Berkule, S., Fierman, A.H., Brockmeyer, C., and Mendelsohn, A.L. 2010. Infant media exposure and toddler development. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 164(12): 1105-1111.

Vandewater, E.A., Bickham, D.S., Lee, J.H., Cummings, H.M., Wartella, E.A., and Rideout, V.J. 2005. When the television is always on: Heavy television exposure and young children’s development. American Behavioral Scientist. 48(5): 562-577.

Vijakkhana, N., Wilaisakditipakorn, T., Ruedeekhajorn, K., Pruksananonda, C., and Chonchaiya, W. 2015. Evening media exposure reduces night‐time sleep. Acta Paediatrica. 104(3): 306-312.

Zimmerman, F.J., and Christakis, D.A. 2007. Associations between content types of early media exposure and subsequent attentional problems. Pediatrics. 120(5): 986-992.

OPEN access freely available online

Natural and Life Sciences Communications

Chiang Mai University, Thailand. https://cmuj.cmu.ac.th

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

The questionnaires and manuals used in the reserch study are provided upon requested to the journal.

Kannika Permpoonputtana1, Jongkon Doungsri2, Sarun Kunwittaya1, Thirata Khamnong1, and Nonthasruang Kleebpung1, *

1 National Institute for Child and Family Development, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom 73170, Thailand.

2 Master of Science Program in Human Development, National Institute for Child and Family Development, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom 73170, Thailand.

Corresponding author: Nonthasruang Kleebpung, E-mail: nonthasruang.kle@mahidol.ac.th

Total Article Views

Editor: Waraporn Boonchieng,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: January 27, 2024;

Revised: May 25, 2024;

Accepted: June 12, 2024;

Online First: June 17, 2024